the Sustainable Approach

Urban-Environmental Design for Sustainable Urban Development

(Safeguarding, Revitalization and Responsibly Utilizing the Natural Assets of the City)

Preface:

Our country lies in an arid, low-rainfall region with a vast desert at its center. The survival of many of our cities depends on one or more natural treasures, in mutual interaction with them.

Our wise ancestors, with deep knowledge of effective systems, structured the relationship between humans, cities, and the surrounding nature in an intelligent and forward-thinking manner—safeguarding natural assets while allowing for their use in line with ecological capacity, thus avoiding gradual degradation.

Until the past century, this balanced and sustainable relationship between city, people, and nature endured across our land. However, in recent decades, urban development plans have prioritized physical expansion, neglecting foresighted strategies to protect cities’ natural treasures. Especially in the last four decades, due to shortsighted and profit-driven management, the destruction of these valuable resources has accelerated.

Examples include:

Mountains and hills: For urban expansion, these were designated for military, recreational, educational, and residential uses. Their slopes were carved for ease of construction, with excavated soil dumped into valleys and lowlands.

Foothill lands: Absorbed into the expanding urban fabric.

Valleys and their surroundings:Due to fertile soil and water access, initially transformed into private gardens, then into garden-villas, and ultimately apartment complexes.

Waterways: Filled with debris from hill excavation or eroded into instability.

River-valleys: Replaced with concrete channels under legislation that ignored environmental considerations. These became waste disposal zones and the remaining land was sold off.

Rivers:Without complete urban wastewater systems, sewage was discharged directly into rivers, turning them into polluted conduits to lakes and seas.

Springs: Legal and illegal upstream construction has degraded water quality and polluted spring sources.

Seas and shorelines: Shores lost their natural purity and value, and the sea was turned into an urban wastewater basin.

Lakes: Unprincipled dam construction has led to the drying of lakes.

Qanats (underground aqueducts): Construction within their buffer zones, illegal water extraction, and sewage contamination have destroyed this invaluable engineering heritage.

Groundwater: Highways and tunnels built without accounting for natural underground water paths have blocked or destroyed them.

Gardens: As key cultural assets of our cities, gardens are losing their resilience due to disrupted water supply routes, destroyed qanats, pollution, and over-construction—and are now rapidly vanishing.

Conclusion:

The above examples demonstrate how, after centuries of resilience, natural resources and environmental heritage are now facing destruction by our generation. In response, experts and nature advocates have worked to propose solutions to halt this destructive trajectory and restore balance. In this spirit, I have—alongside fellow committed colleagues and drawing on experience with nature-based projects—proposed the theory of Urban–Environmental Design. A theory that, by interrupting the current course of degradation, enables responsible use of natural treasures and supports sustainable development of our cities and country. It is hoped that this effort will play a positive role in achieving its intended goals.

Definition of Urban–Environmental Design:

Wherever a city influences—or is influenced by—a natural element within or around its boundaries, all planning must prioritize rules, regulations, and guidelines rooted in environmental studies, landscape design, and related sciences—these must form the foundation for urban development plans in the domains of urbanism, urban design, and allied disciplines.

Achievements of the Urban–Environmental Design Theory in Iran:

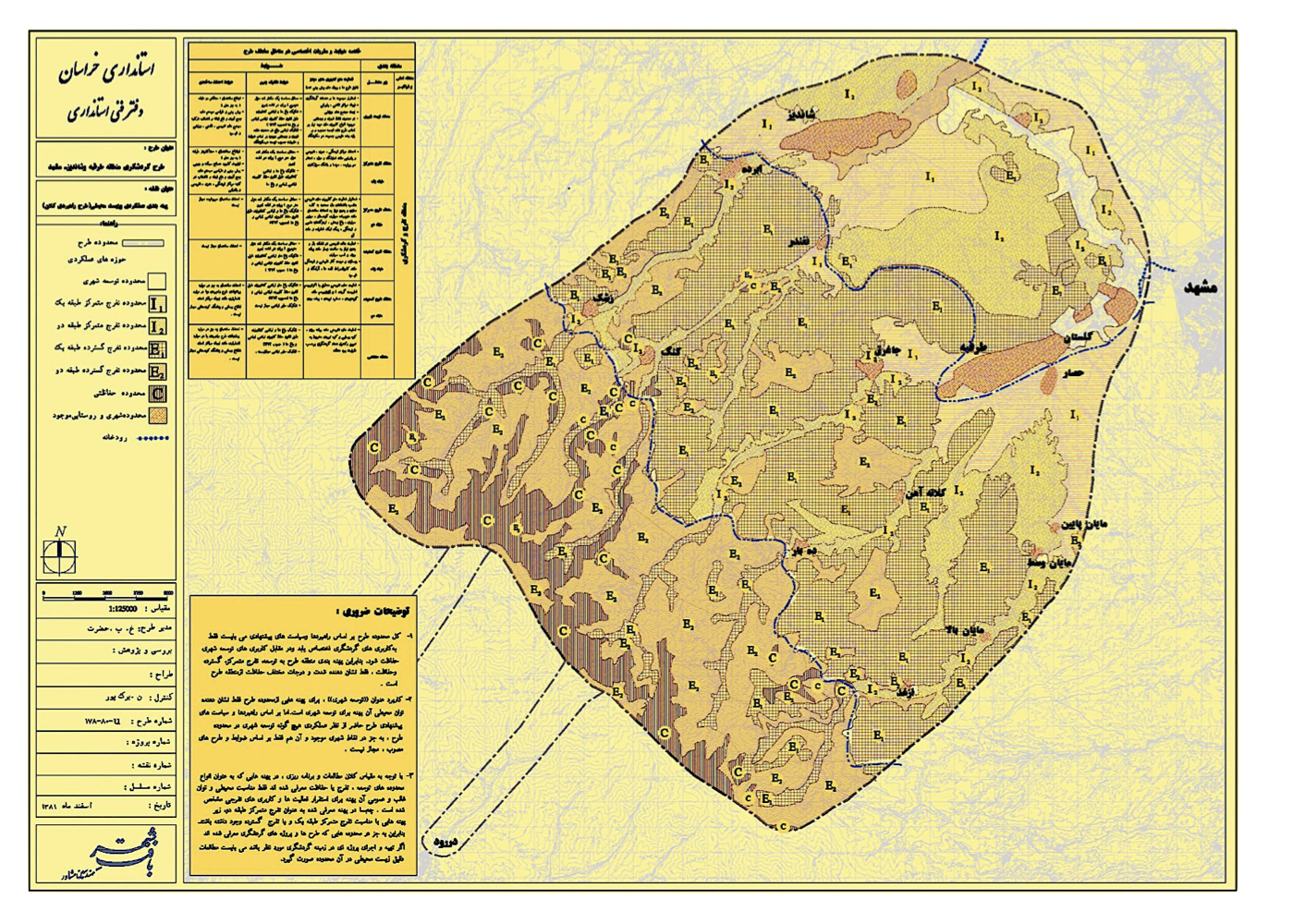

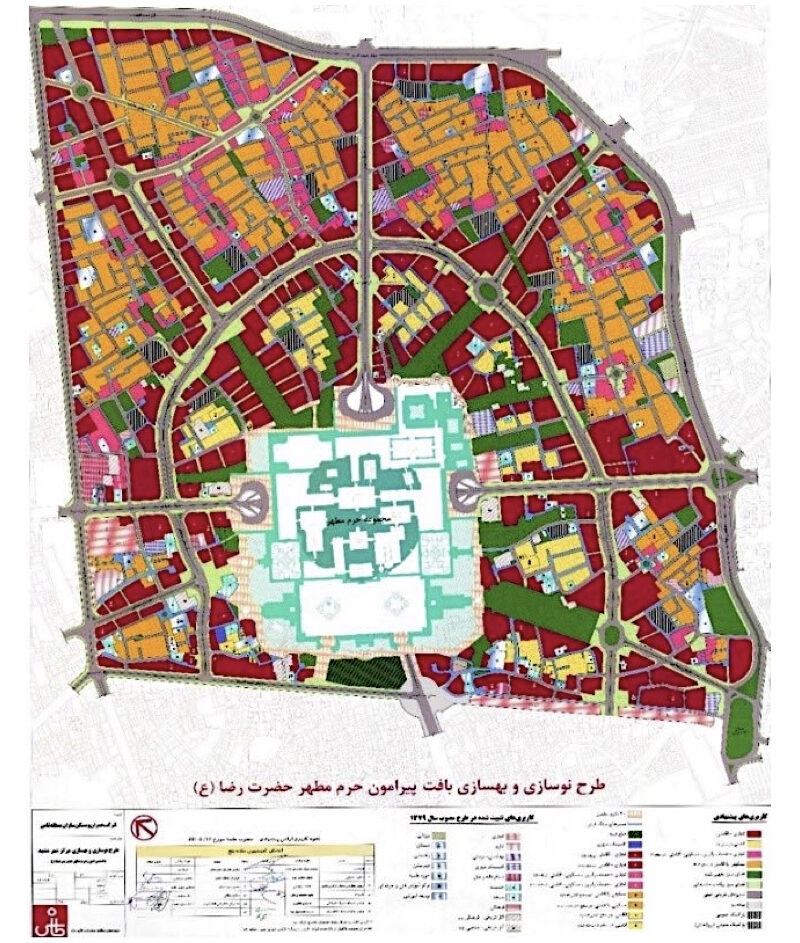

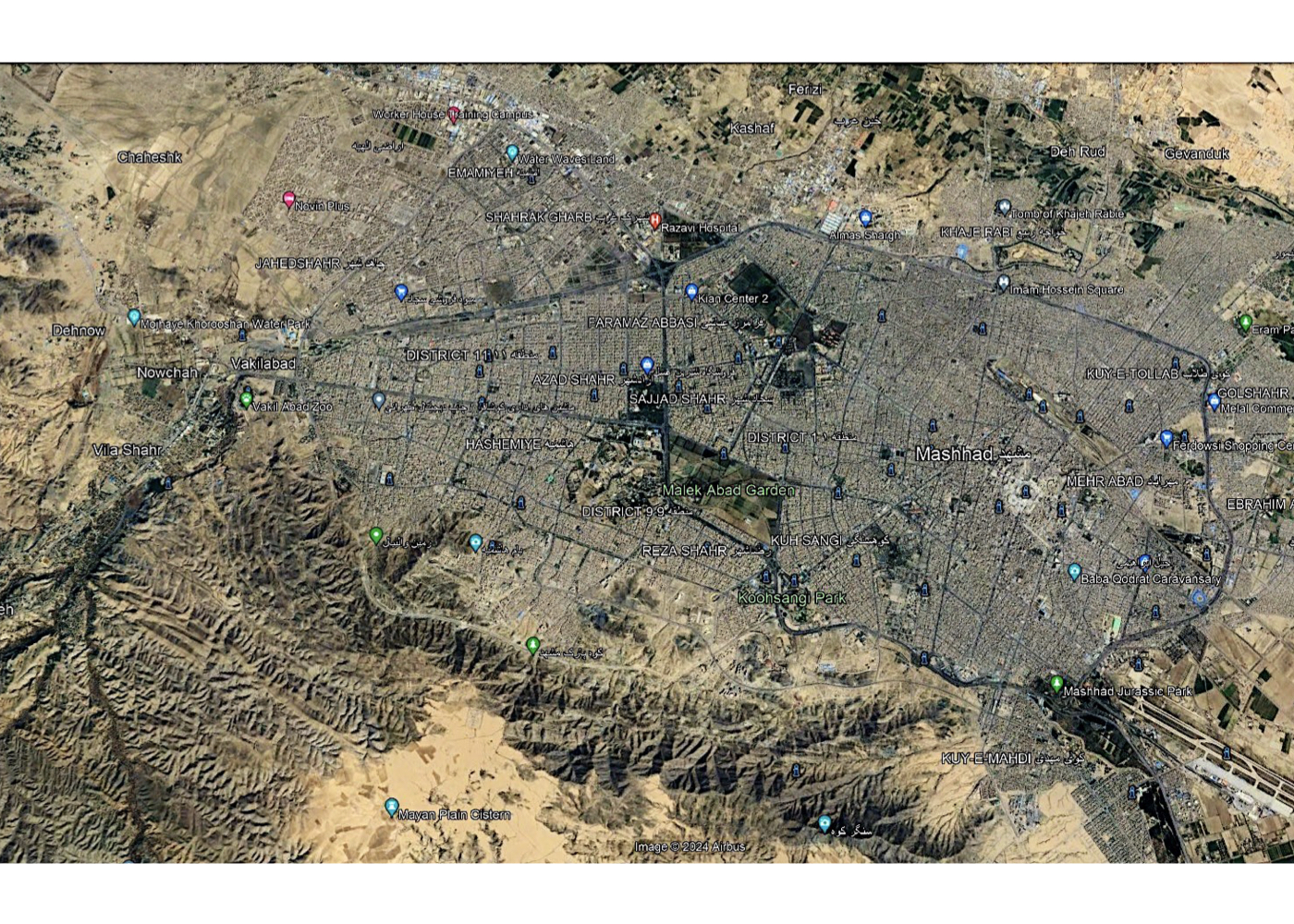

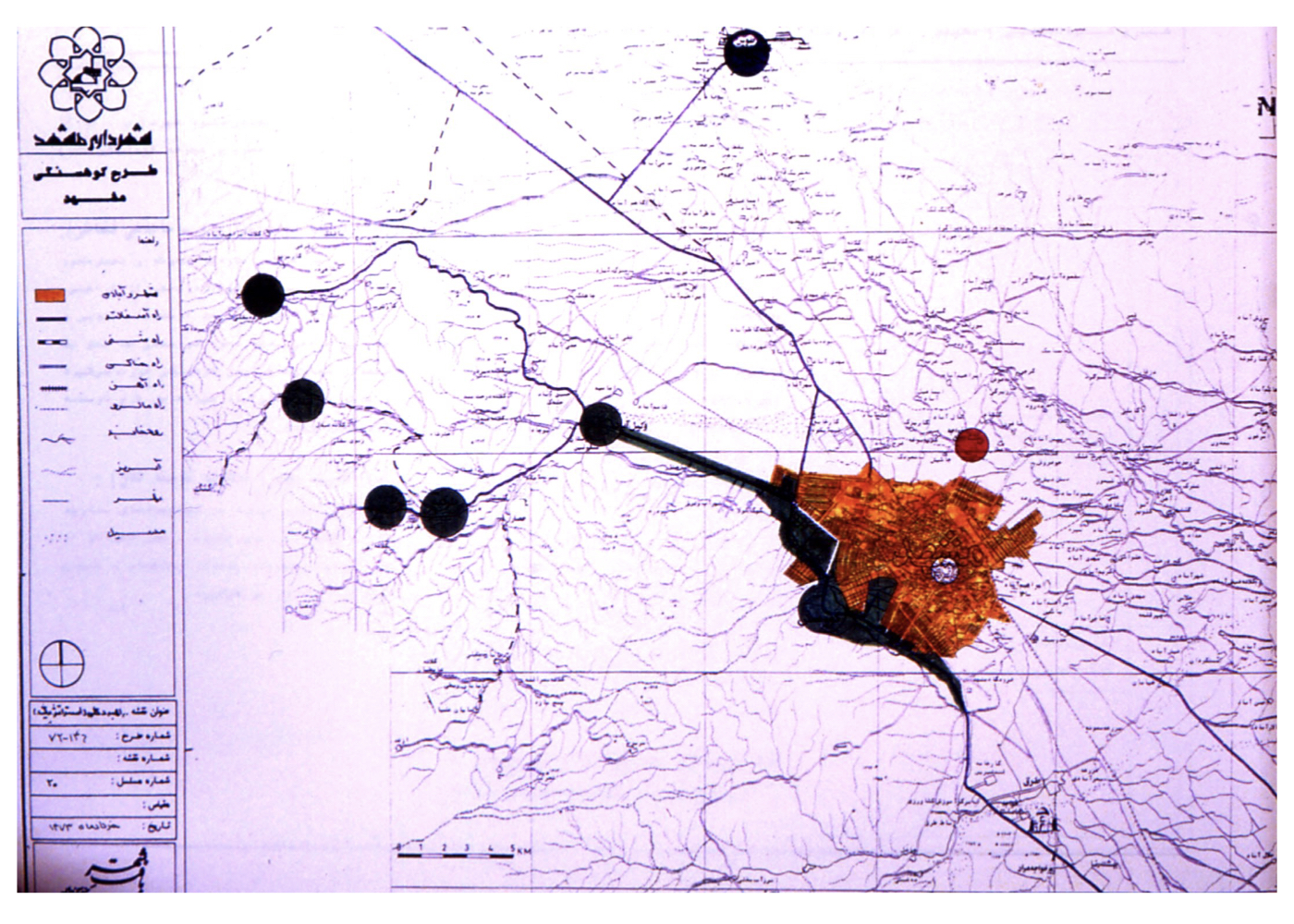

Over the past four decades, I have had the honor of directing the planning and design studies of several valuable natural assets in cities across the country. These projects were prepared and proposed based on the theory of “Urban–Environmental Design” and could have simultaneously protected and enhanced the environmental quality of these natural assets—resources that are the wealth, heritage, and foundation for continued healthy urban life—while enabling equitable, capacity-aligned, and sustainable use by citizens, improve people’s attitudes and relationships with nature, and contribute meaningfully to sustainable urban development.

However, fundamental changes to the plans, their incomplete implementation, or execution without the involvement of the original designers and under non-expert directives, often lead to deviation from the original vision, potentially causing harm, and distancing the project from its core objectives of natural resource protection and sustainable use.

The reports for these projects have been compiled over the years across various cities, amounting to several hundred volumes, and were developed through national funding and the dedicated efforts of experienced, committed professionals.

While it is not feasible to present all these reports here, summarizing the strategies, approaches, and recommendations of these projects for each city’s residents especially students and younger generations can raise awareness about the unique natural and historical values of our cities and nation, and foster their engagement in preserving these natural treasures and priceless generational heritage.

A Few Important Notes Regarding These Projects:

Some proposed strategies—such as enhancing human-nature-city interaction—are generalizable and applicable to similar urban contexts. In many of these cities, other relevant plans exist that are not covered here. Some plans were not executed—or only partially realized—due to funding gaps or changes in administration. In Section 8 of this website, information is provided on 42 urban–environmental design projects across 18 cities in Iran.

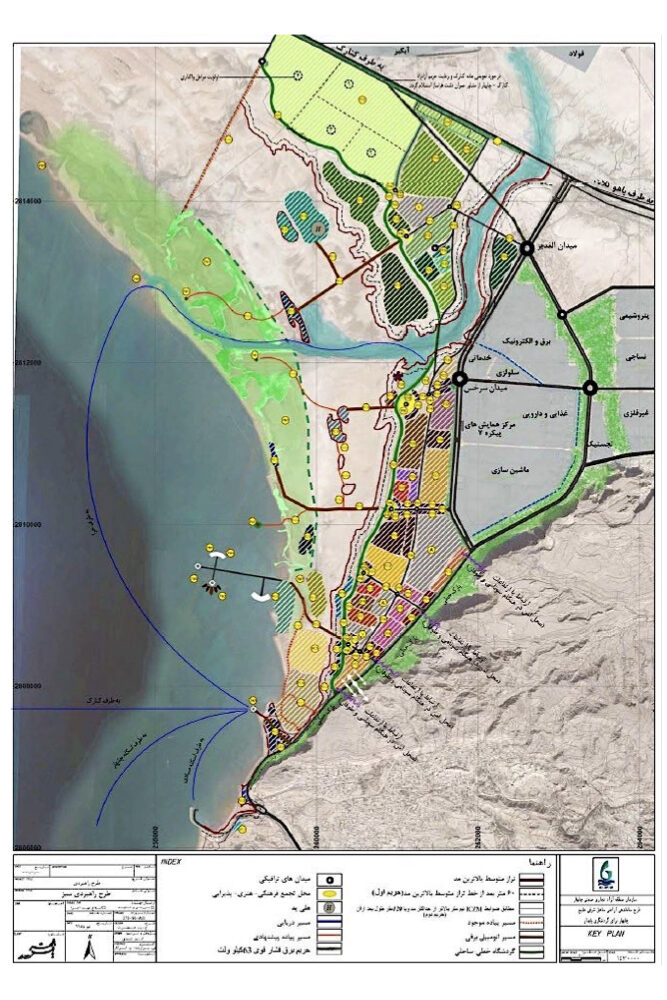

ARAK

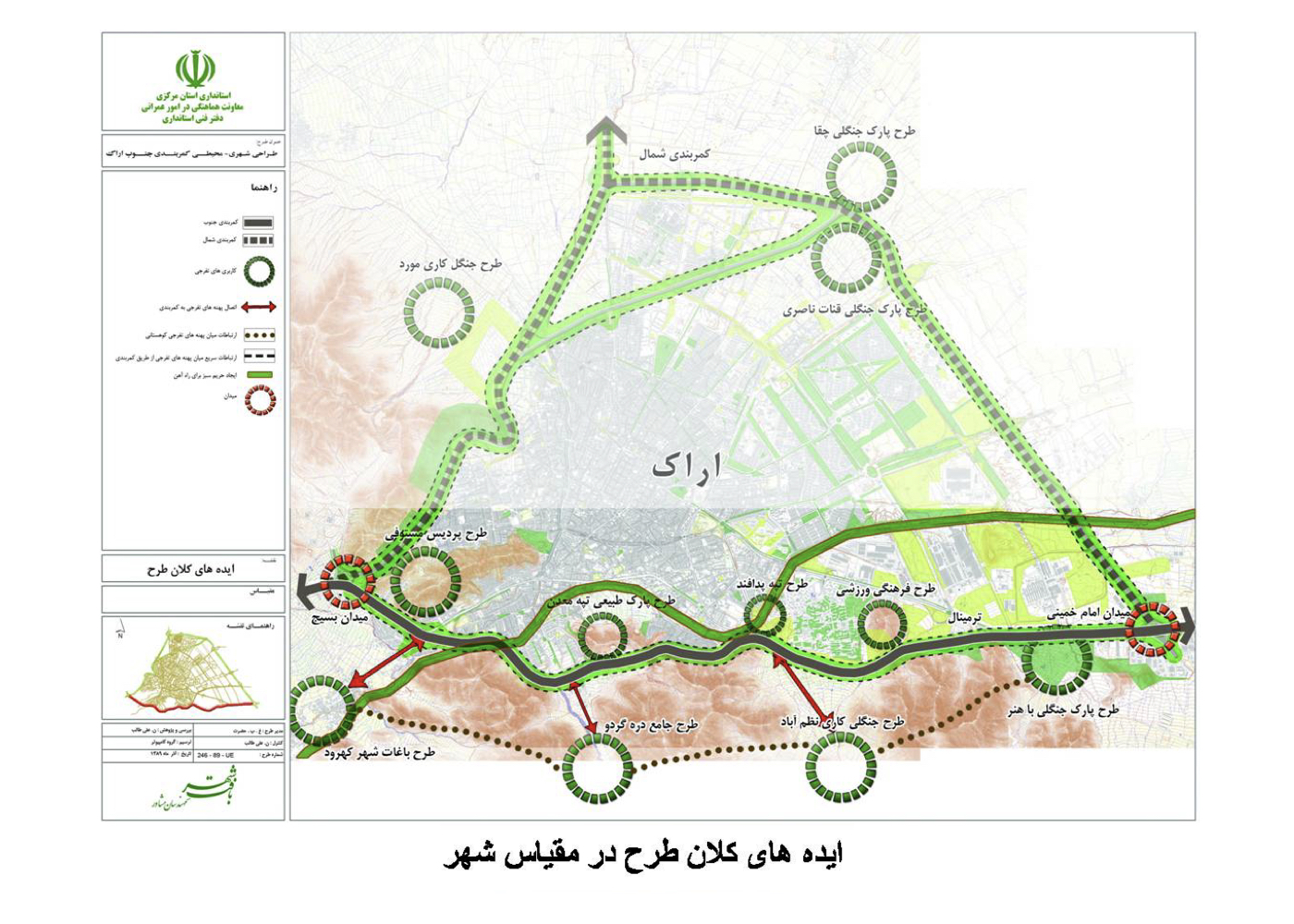

Urban – Environmental Design of Arak Ring Roads

Background:

Arak is one of the major industrial centers in Iran, and the presence of numerous factories has led to severe air pollution, resulting in a rise in respiratory illnesses among residents. City officials and the provincial government initiated a joint effort to expand urban green spaces wherever possible and requested collaboration from the consultant. Taking into account all constraints and opportunities, the following plans were prepared and approved:

1. Urban–Environmental Design of the Southern Ring Road Corridor

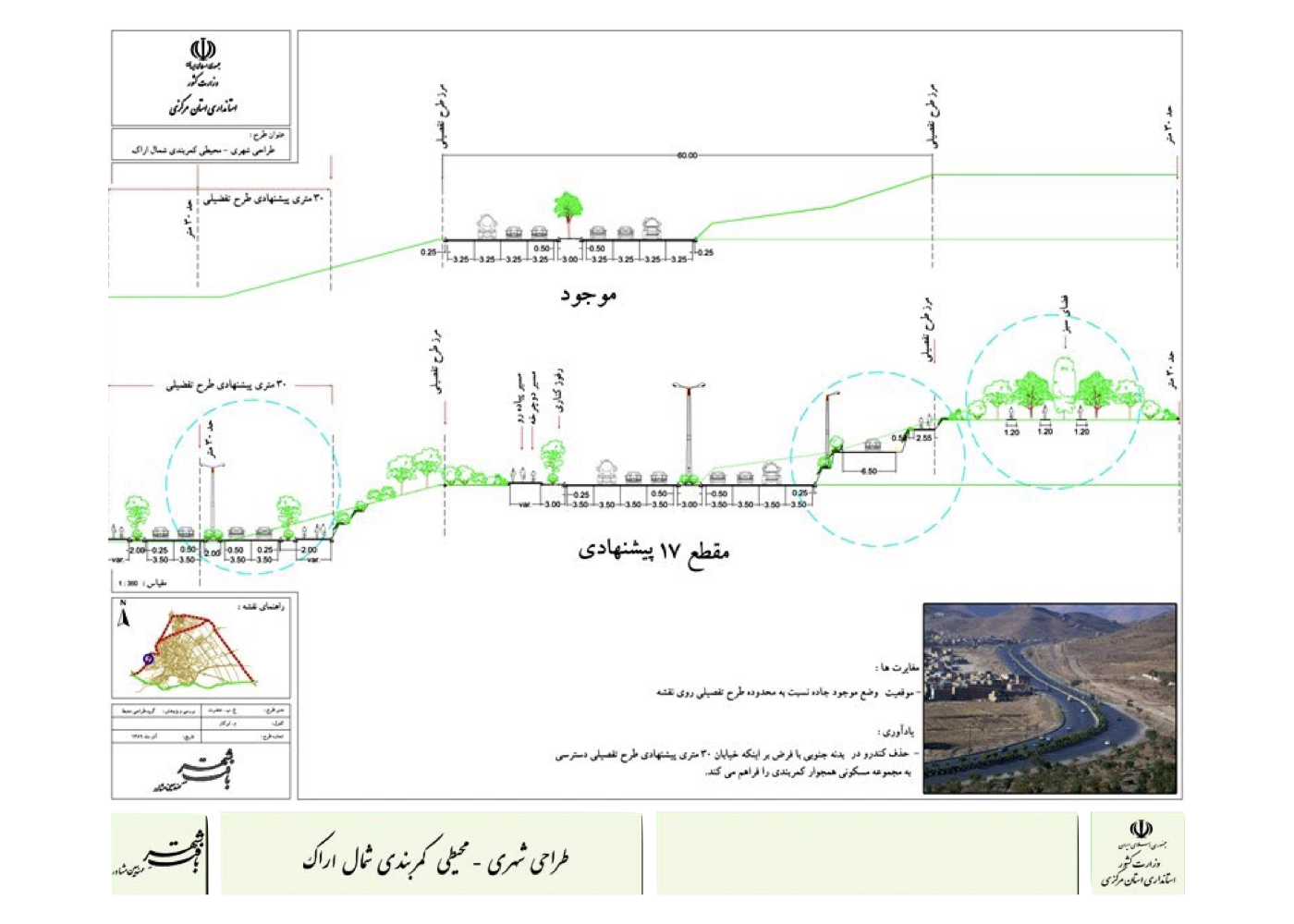

2. Urban–Environmental Design of the Northern Ring Road Corridor

3. Urban–Environmental Design of the Four Main Gateways to the City

4. Urban–Environmental Design for Mount Mostofi

5. Urban–Environmental Design for Mount Gerdoo (Stone Quarry)

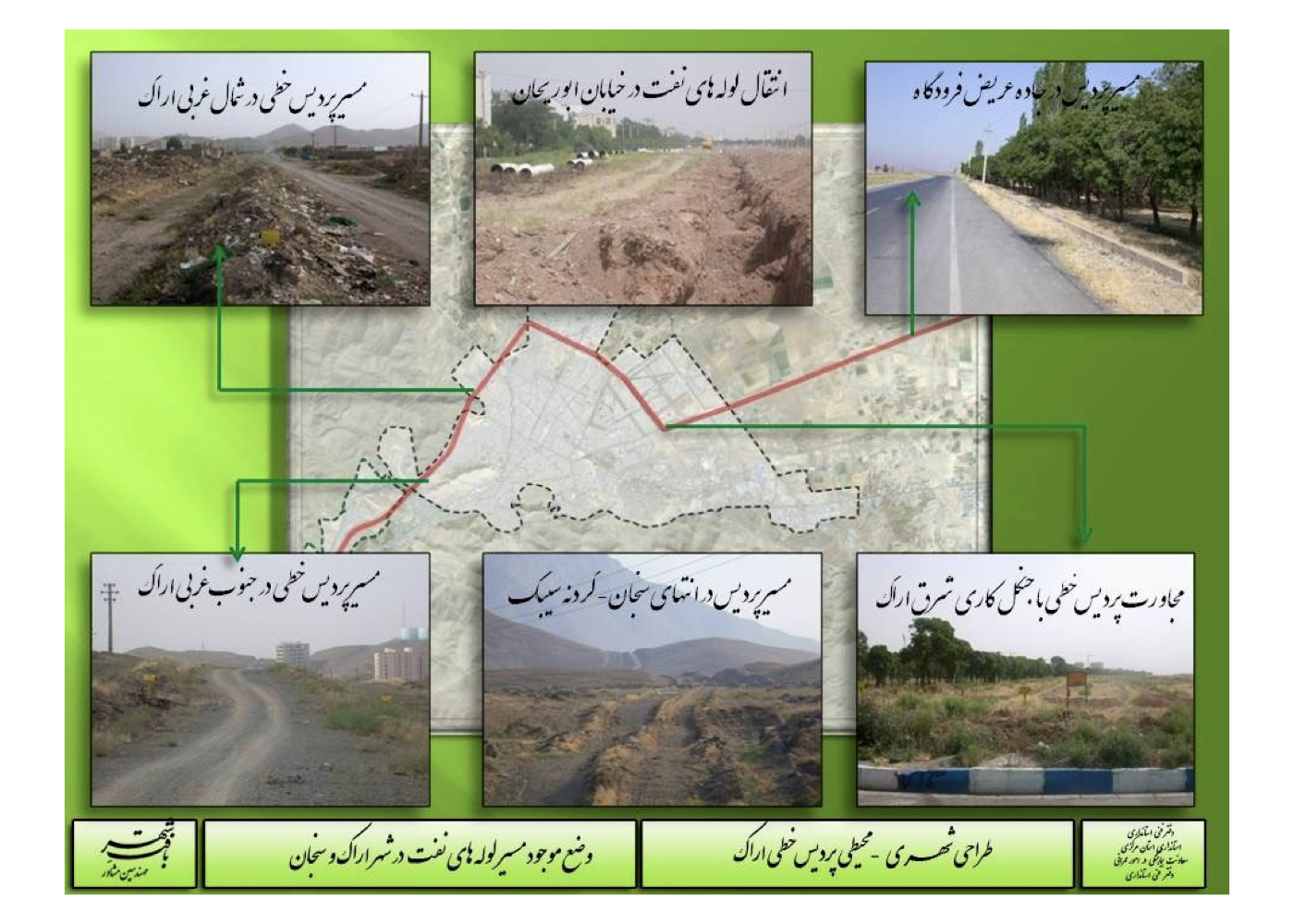

6. Urban–Environmental Design of the Oil Pipeline Route Within the City

Implementation Status:

Of these plans, ten kilometers of the southern ring road and Mount Mostofi have been implemented, but due to administrative changes and possible budget constraints, follow-up on the implementation of the remaining projects has not continued.

Importance and Vision of the Plan:

Implementing green corridors along the highways could have formed a continuous green belt, significantly contributing to air pollution reduction, while the greening of the mentioned mountains and the oil pipeline corridor could also aid in air purification.

Detailed explanations for projects 4, 5, and 6 are provided in the respective project profiles, while maps for projects 1, 2, and 3 are available on this same page.

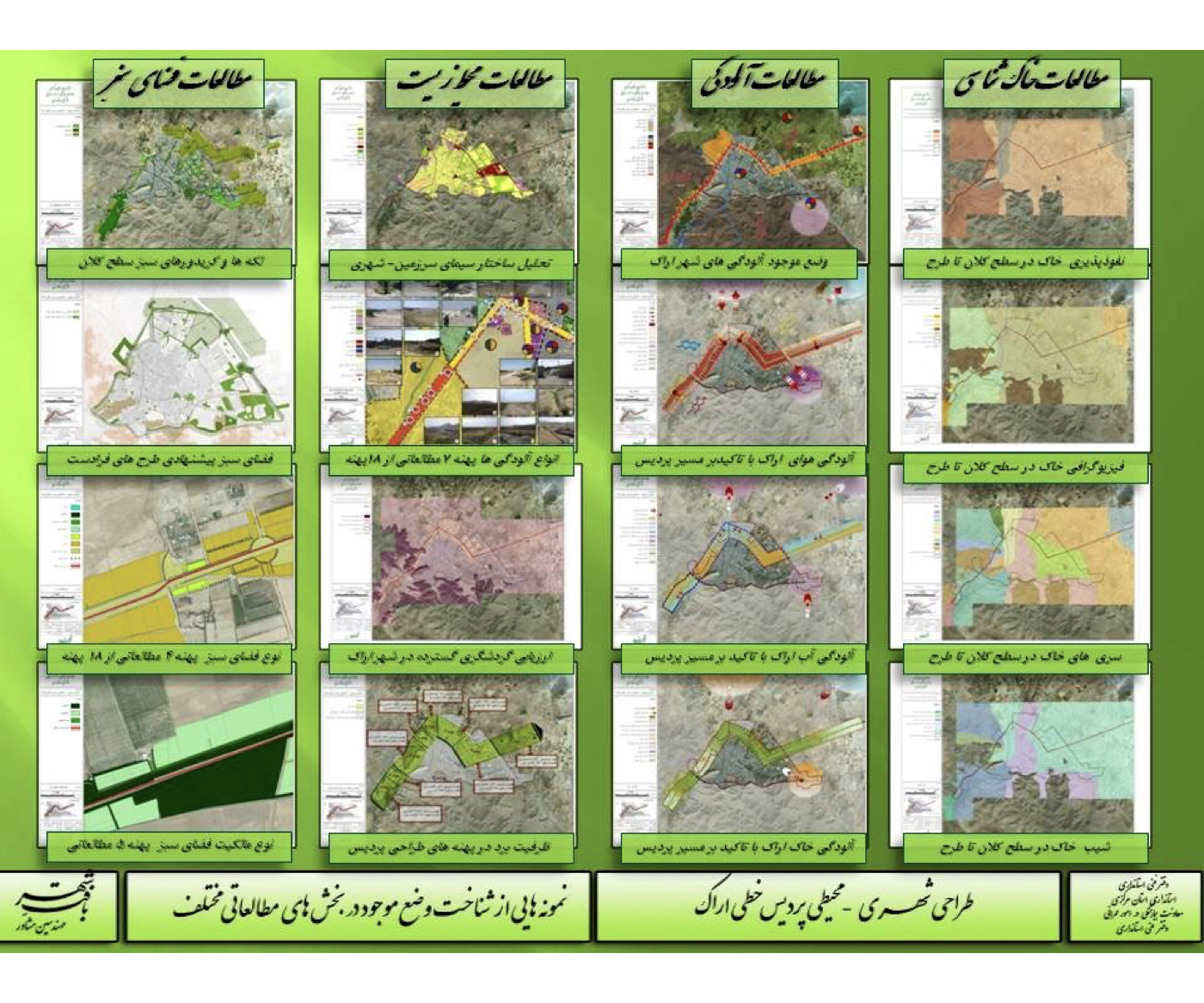

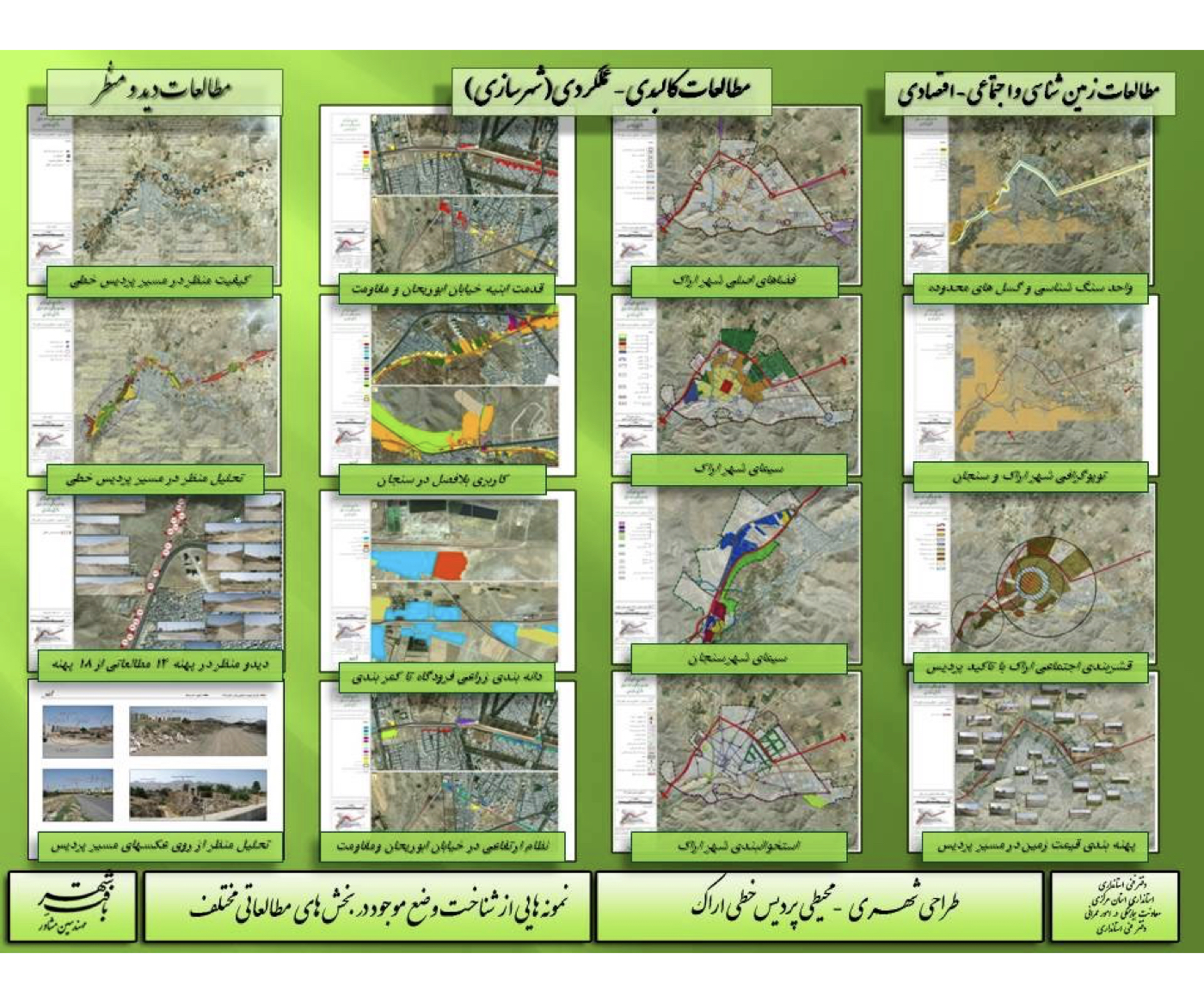

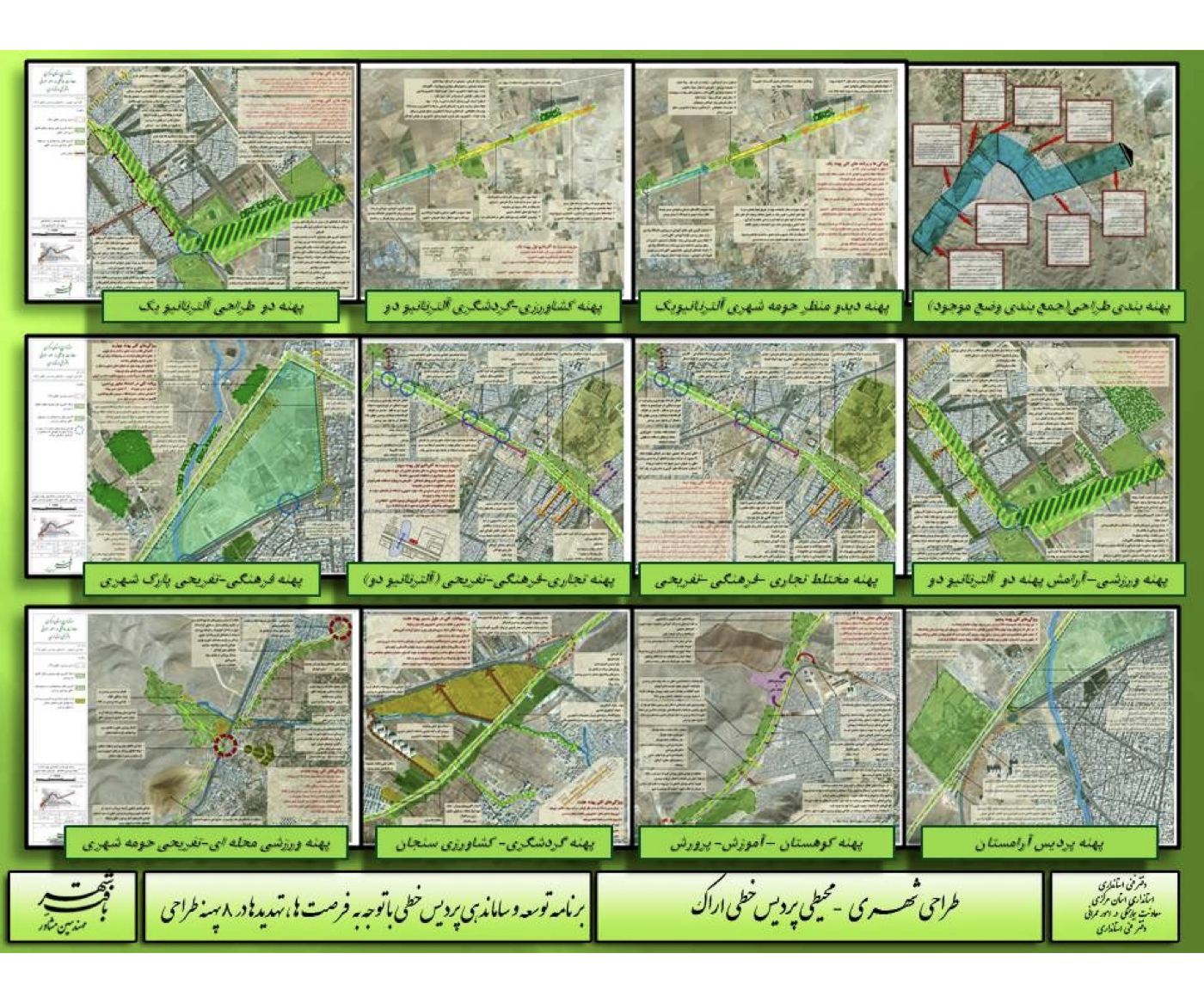

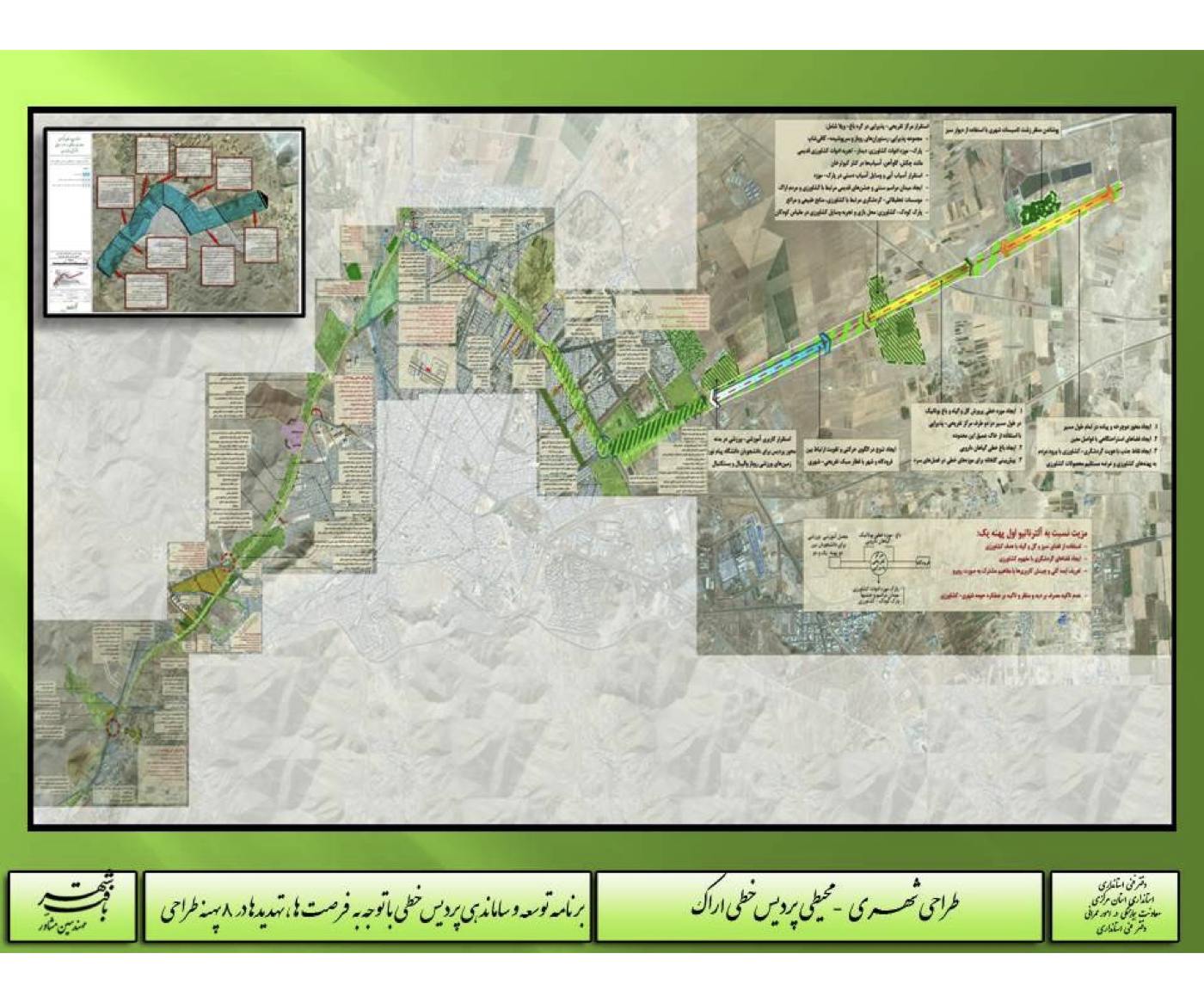

Urban – Environmental Design of the Linear Paradise (Strategic)

Summary of Proposal:

Transforming a polluted industrial corridor into one of the city’s natural assets

Background:

In the city of Arak, a petroleum pipeline has passed through the area for several decades, and with urban expansion, it has come into close proximity with residential zones, causing contamination at both surface and subsurface levels in several locations.

The provincial government and municipality decided to decommission the pipeline and repurpose its corridor. Comprehensive urban–environmental studies were conducted in all relevant domains, and it was recommended that, due to Arak’s air pollution, this corridor be transformed into a Linear Green Paradise (Linear Urban Park) enabling adjacent neighborhoods to use it for walking, recreation, and exercise, with its greenery helping to mitigate urban air quality issues.

The plan involved studies in geology, soil science, environmental pollution, green space planning, urbanism, visual landscape, and connectivity, and based on existing conditions, the corridor was divided into 8 evaluated zones.

Within this framework, the following concepts and solutions were proposed and approved:

Summary of the Proposal’s Concepts and Solutions:

1. Soil remediation along the route

2. Integration of unused triangular or irregular leftover plots into the park

3. Linking fragmented urban green spaces to the corridor to form a continuous, resilient green network against air pollution

4. Increasing vegetation density in adjacent urban green spaces

5. Building football and multipurpose sports fields to reinforce the recreational function of the corridor

6. Connecting Sanjan Boulevard to the gardens of Sanjan valleys through the linear park

7. Establishing physical and functional integration between the linear park and Arak city center

8. Proposing width variation templates along the park based on land use, urban nodes, and access shifts

9. Designing areas to be annexed to the park based on land owned by the Housing and Urban Development Organization

10. Providing planting and design schemes (stone retaining walls, slope stabilization, rest zones, emergency paths, pedestrian and bicycle routes, parking areas, children’s playgrounds, foothill transitions, hospital-edge plantings, infrastructure screening, “Garden of Tranquility,” food and service zones, etc.)

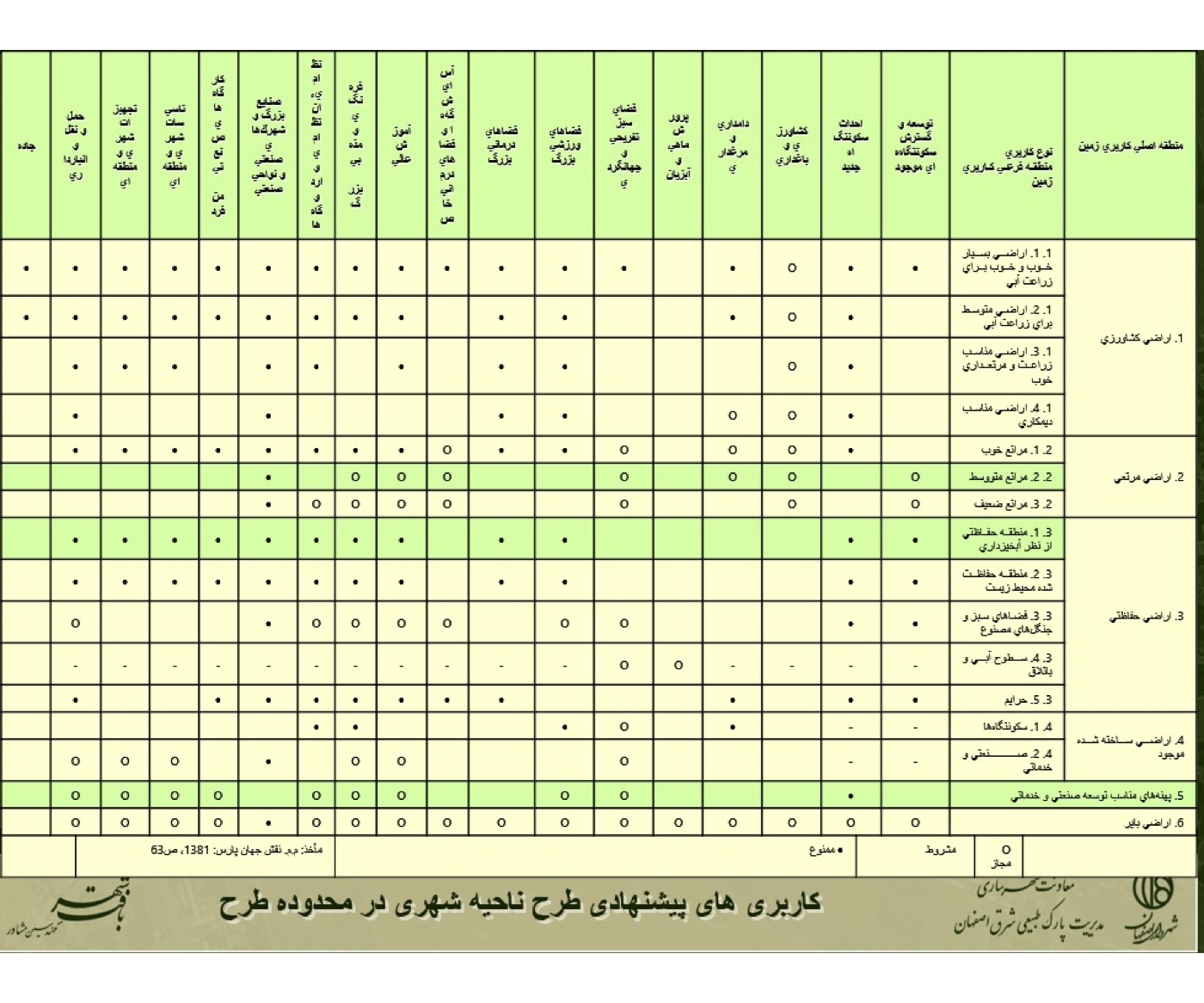

ISFAHAN

Urban – Environmental Design of Polluted Southeastern Lands (Strategic)

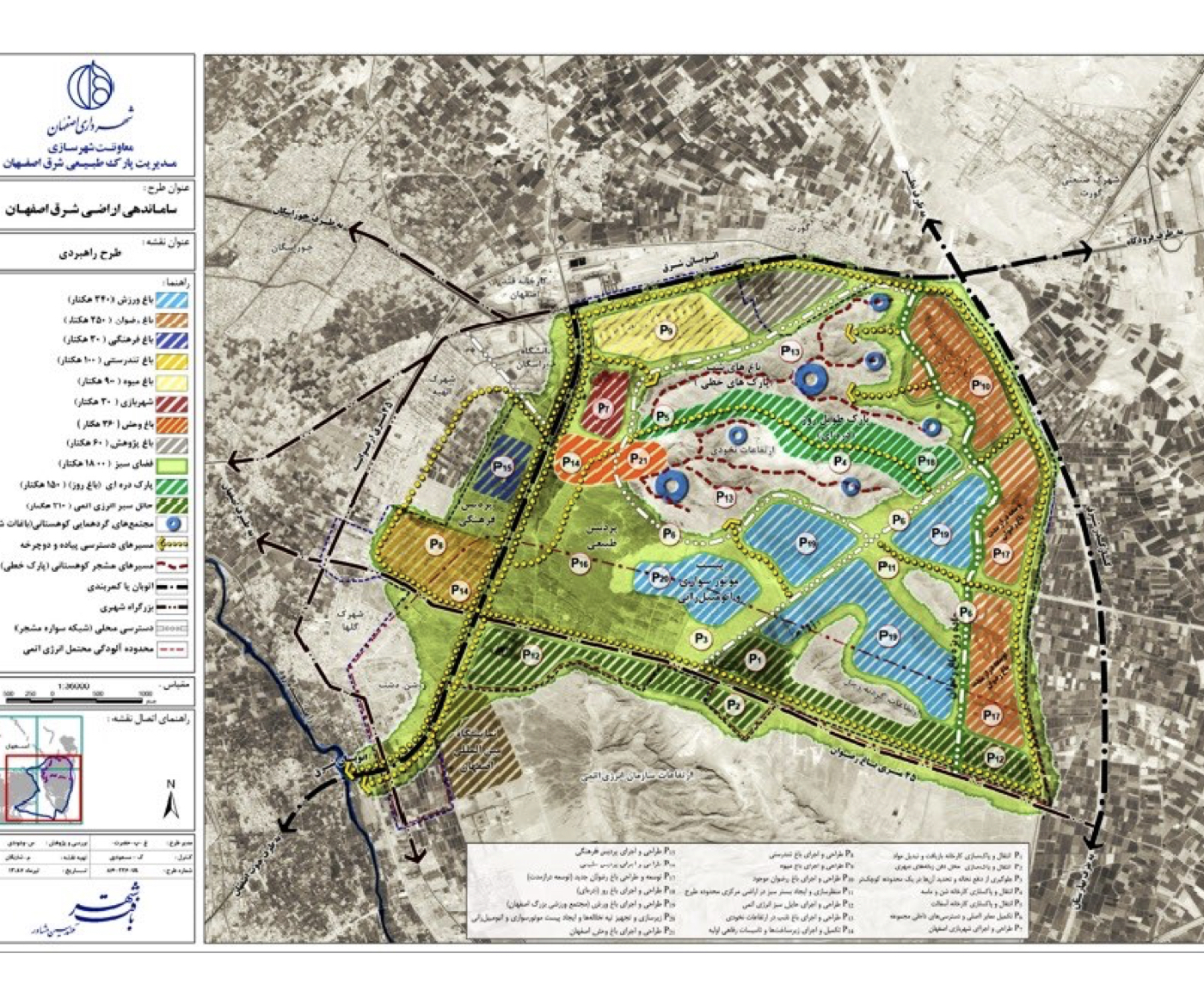

A portion of land in southeastern Isfahan is bounded on one side by surrounding mountains and on the other by agricultural lands to the south of the city. In recent decades, this area has served as a landfill for municipal waste and debris. It is also surrounded by uses such as a compost facility, asphalt factory, Isfahan’s cemetery, and nuclear energy installations. The study area covers approximately 3,000 hectares.

The Municipality of Isfahan commissioned the consultant to conduct a strategic-scale study and propose solutions for pollution reduction, land transformation, and the optimal reuse of these lands. Comprehensive studies were carried out to assess threats, constraints, opportunities, and potentials across relevant fields—urban planning, architecture, environmental science, landscape design, urban economics, and various types of pollution and their spatial impacts on the city and its surroundings. Naturally, the most critical environmental issues in southeastern Isfahan were identified, including the impact of industrial and municipal activities on soil, water, and air quality. The project’s strategic framework was developed by aligning global best practices from other major cities with the region’s specific environmental context, proposing a phased 25-year implementation timeline.

Concepts and Strategic Directions:

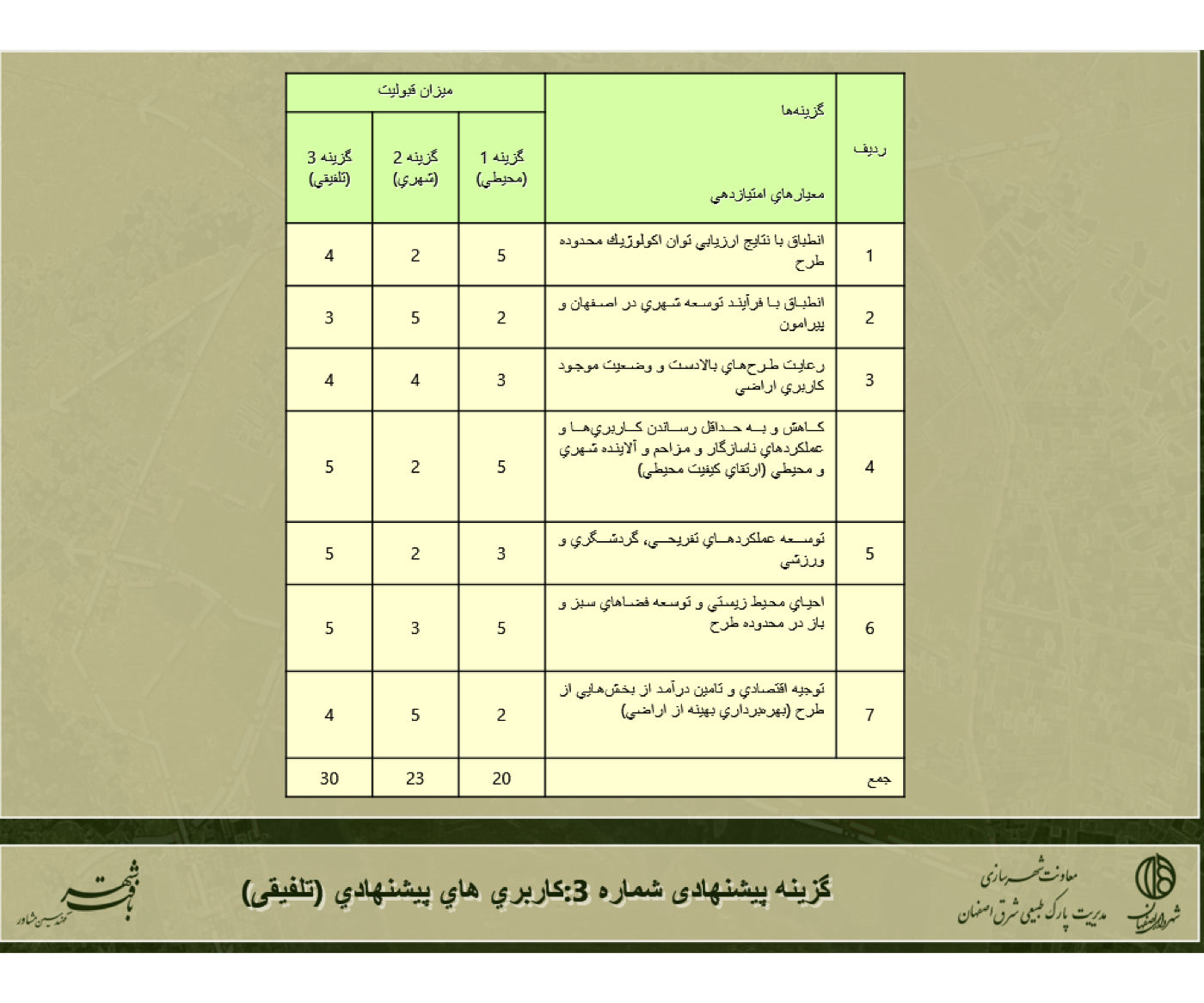

These components were summarized across several strategic tables, as follows:

1. Proposed Land Uses for the Urban District within the Project Boundary

2. Environmental Policies

3. Urban–Physical Development Policies

4. Proposal of Three Planning Scenarios

5. Recommended Land Use Plan (Integrated Model)

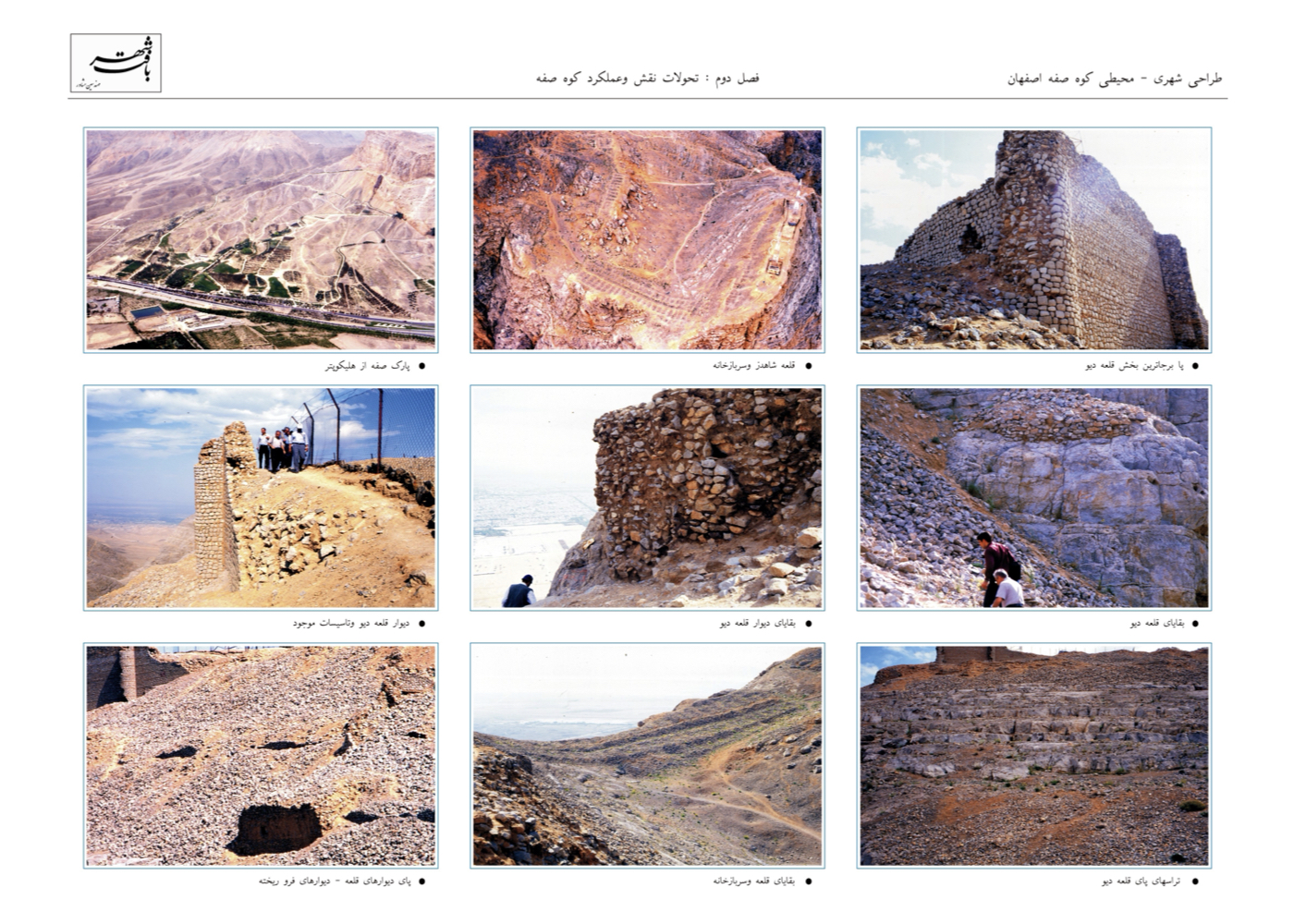

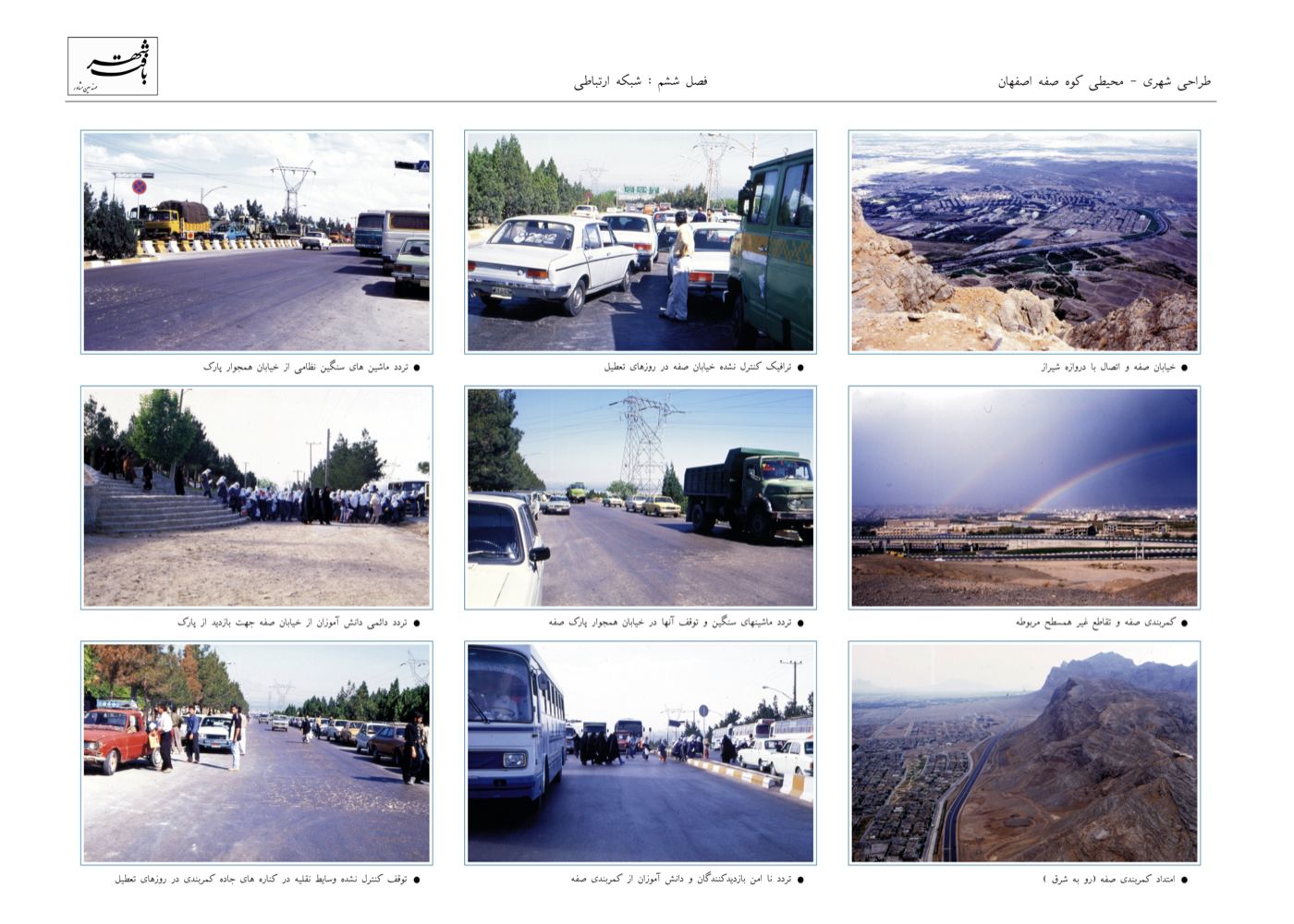

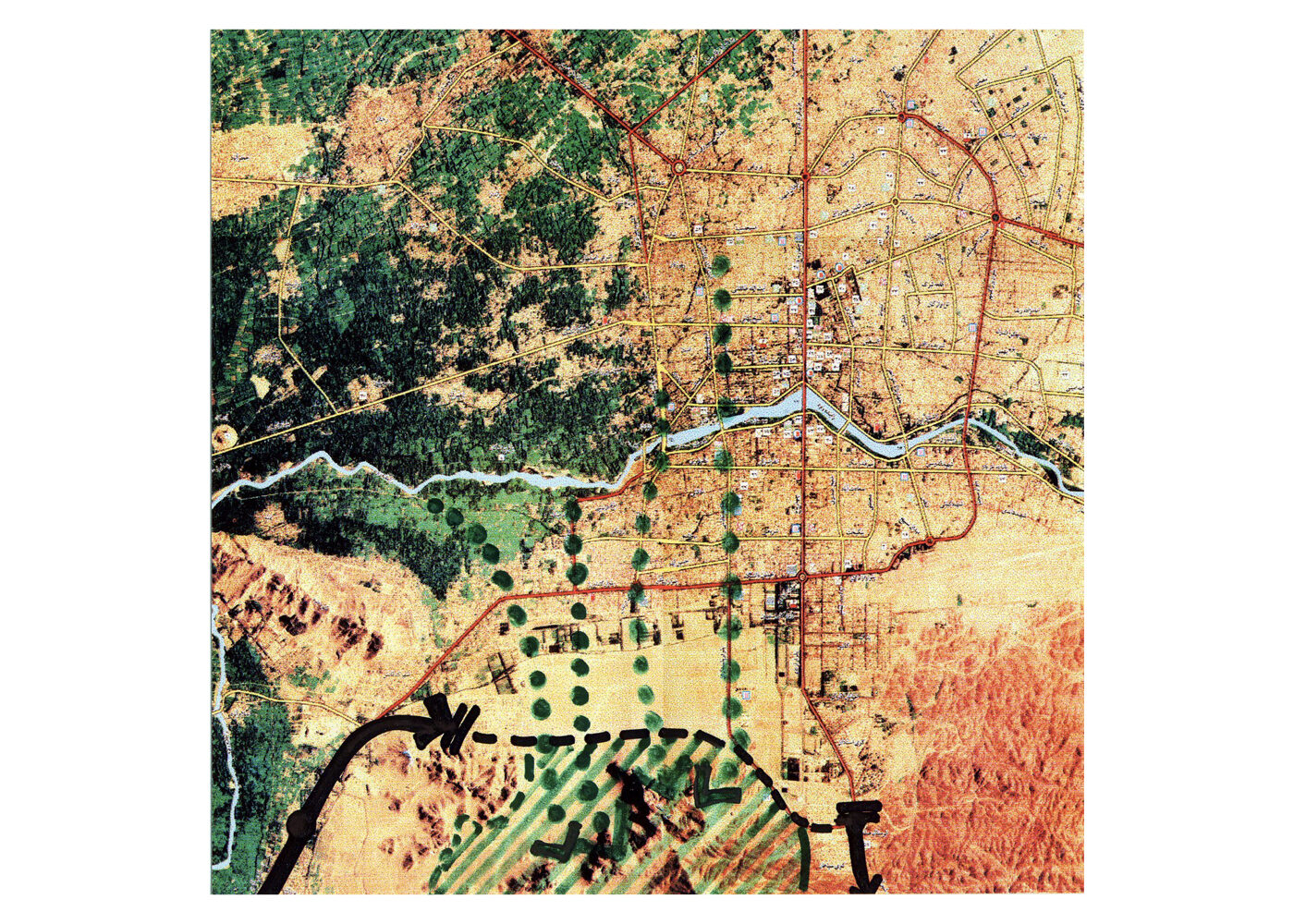

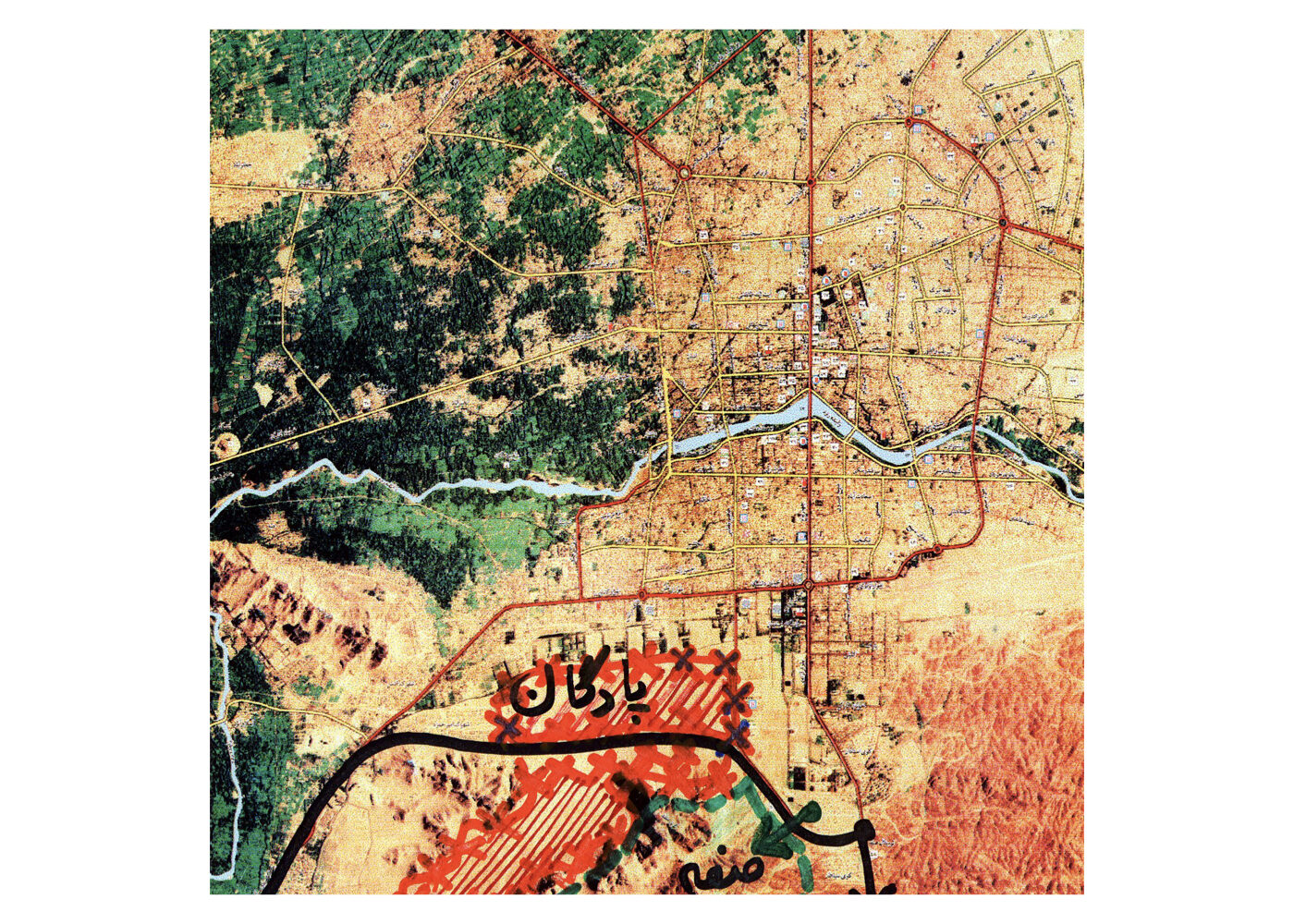

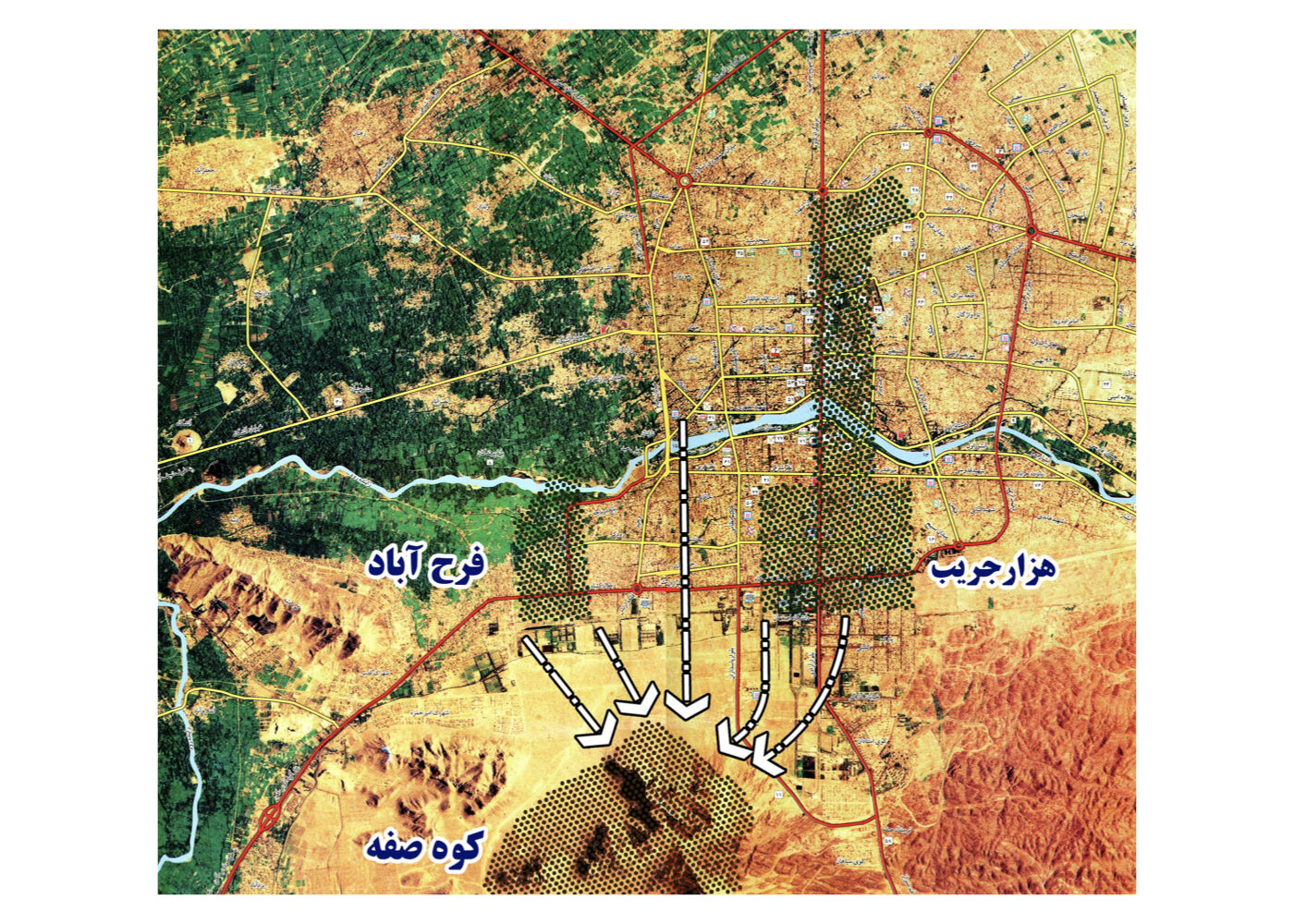

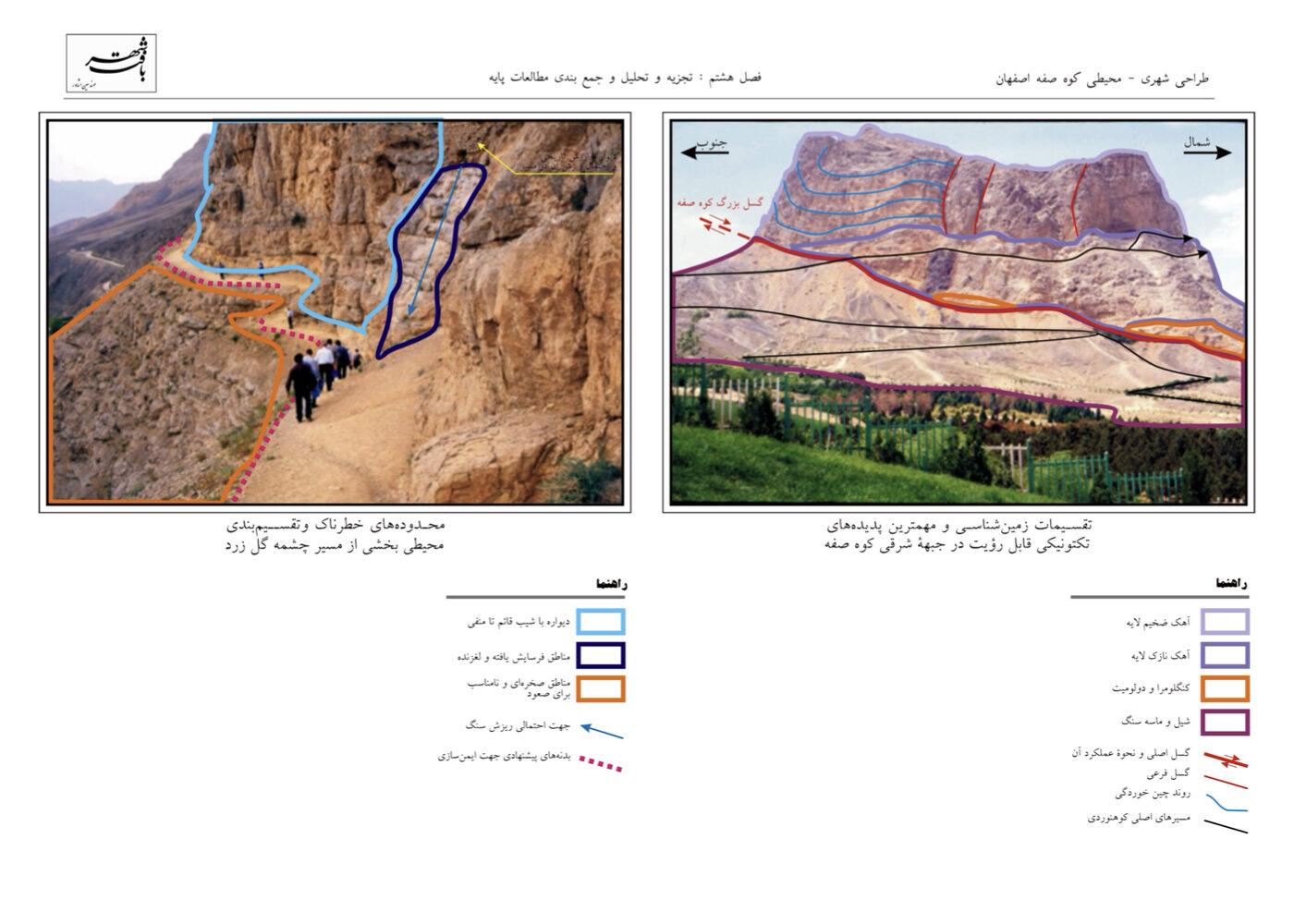

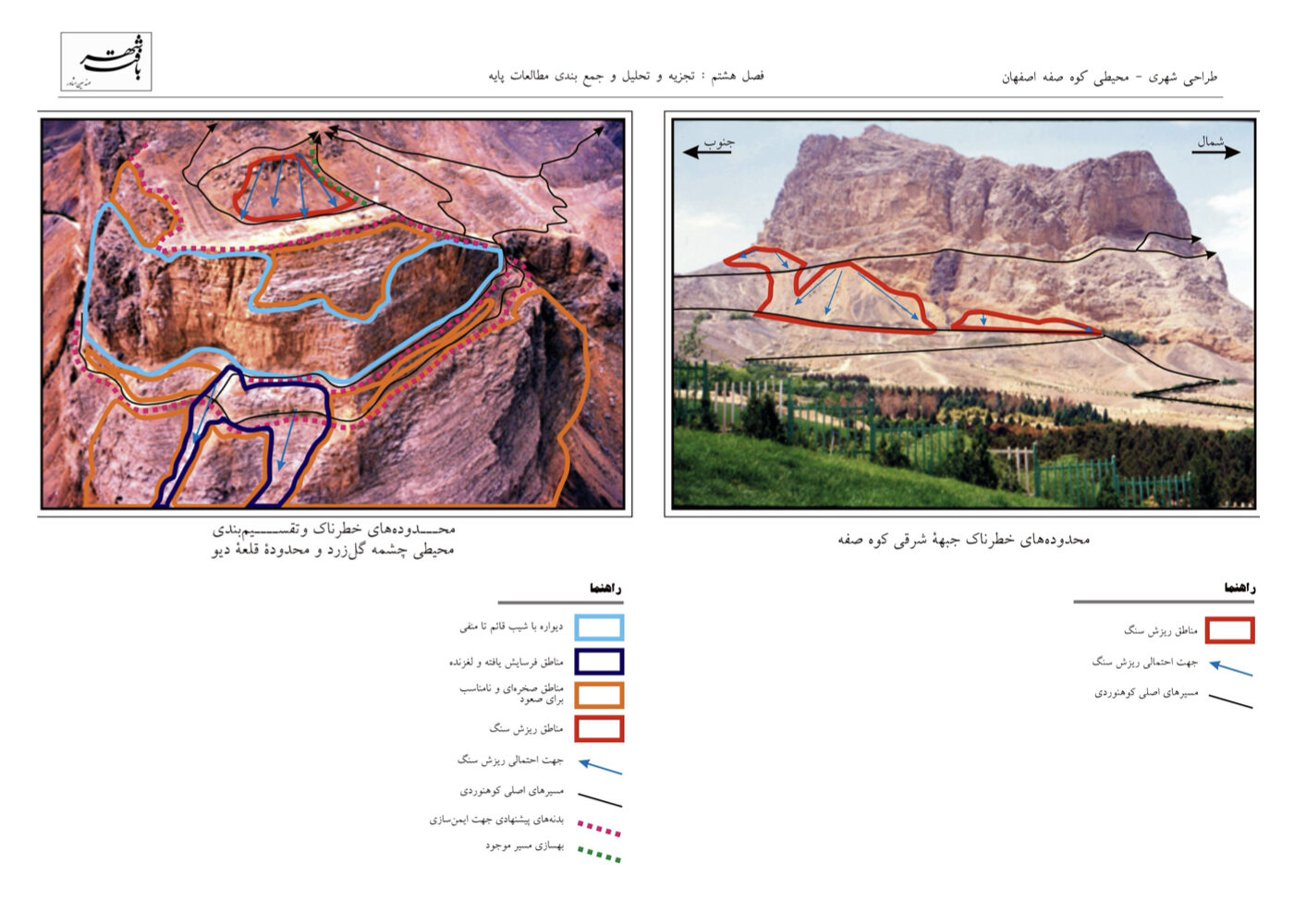

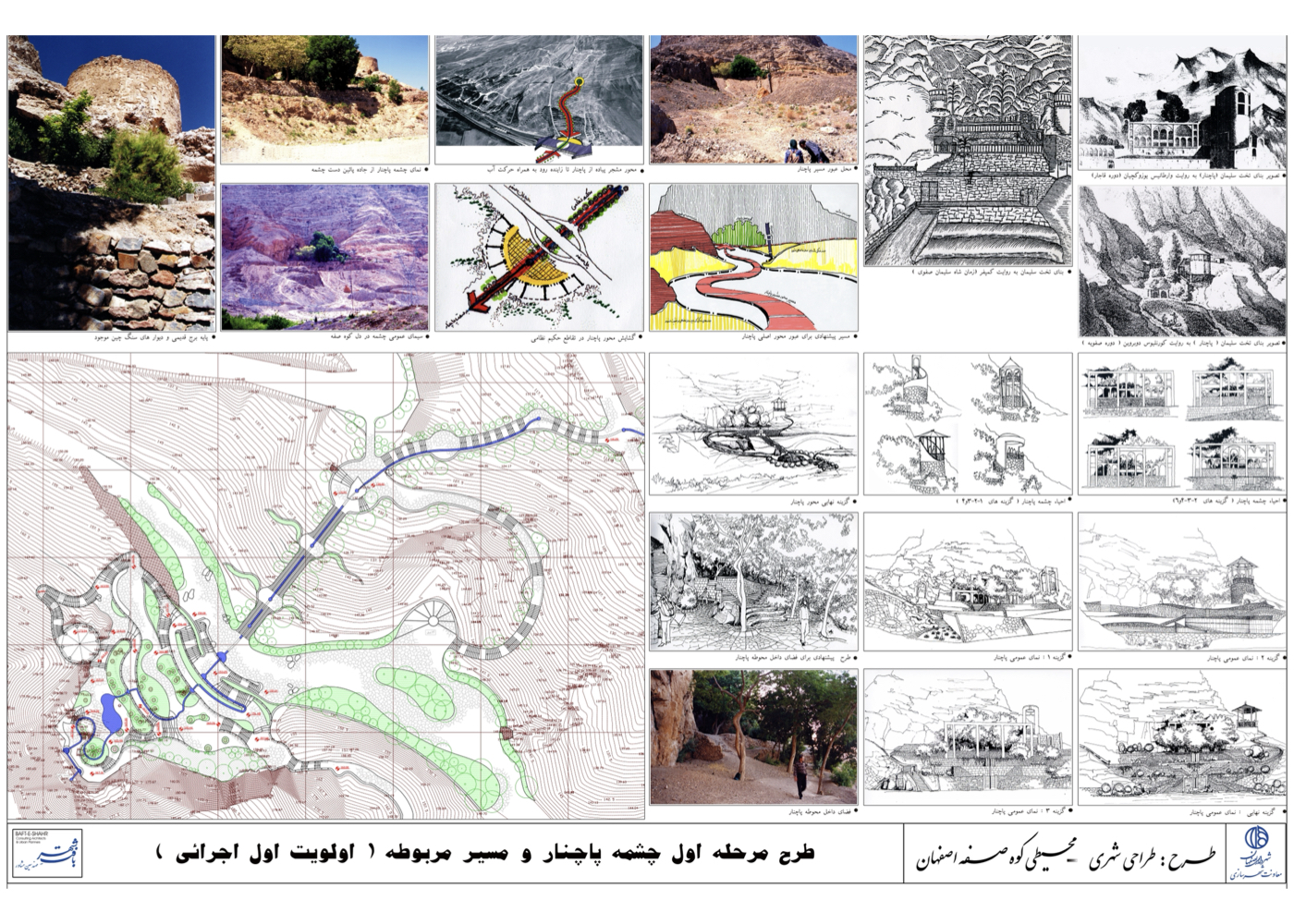

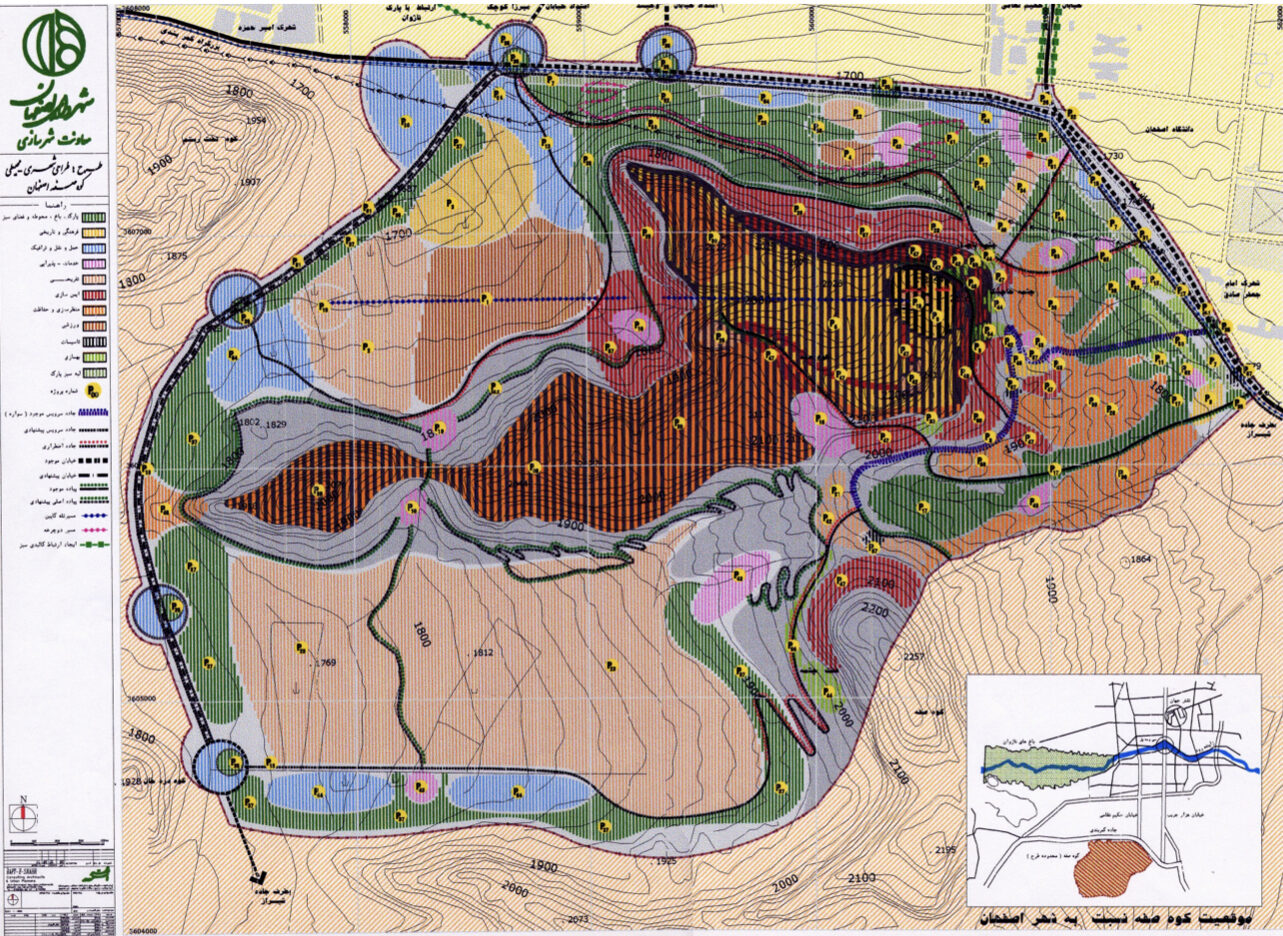

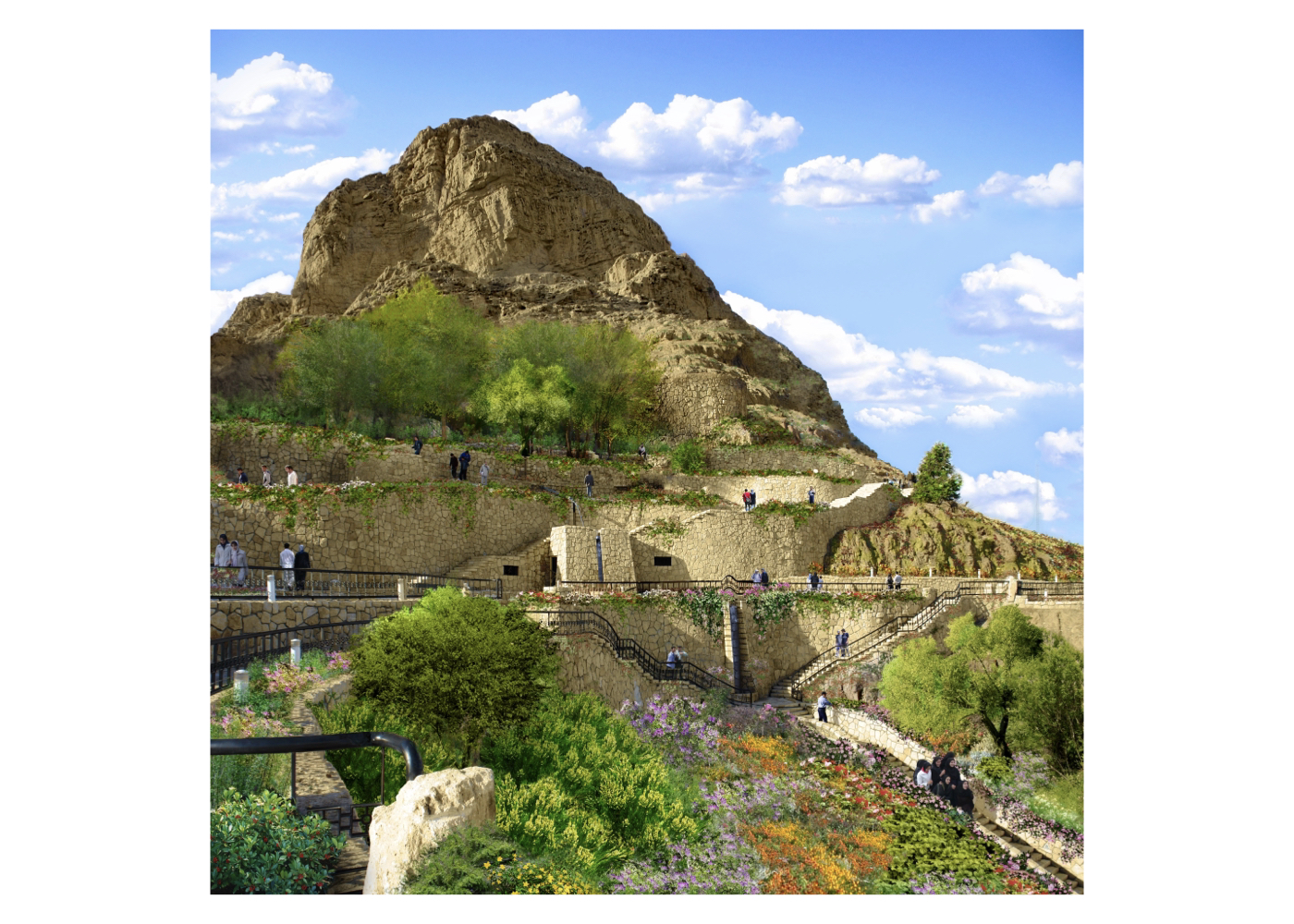

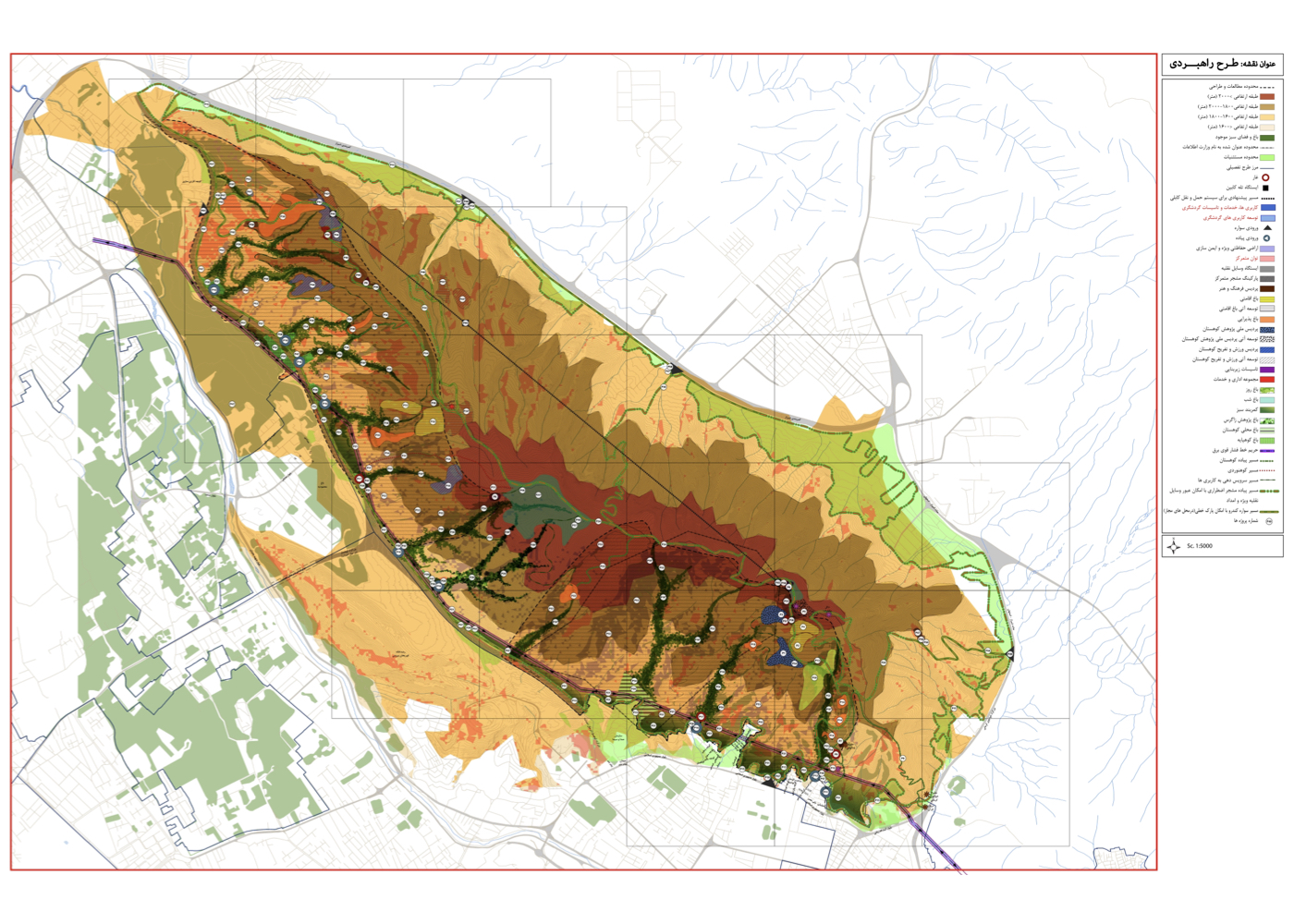

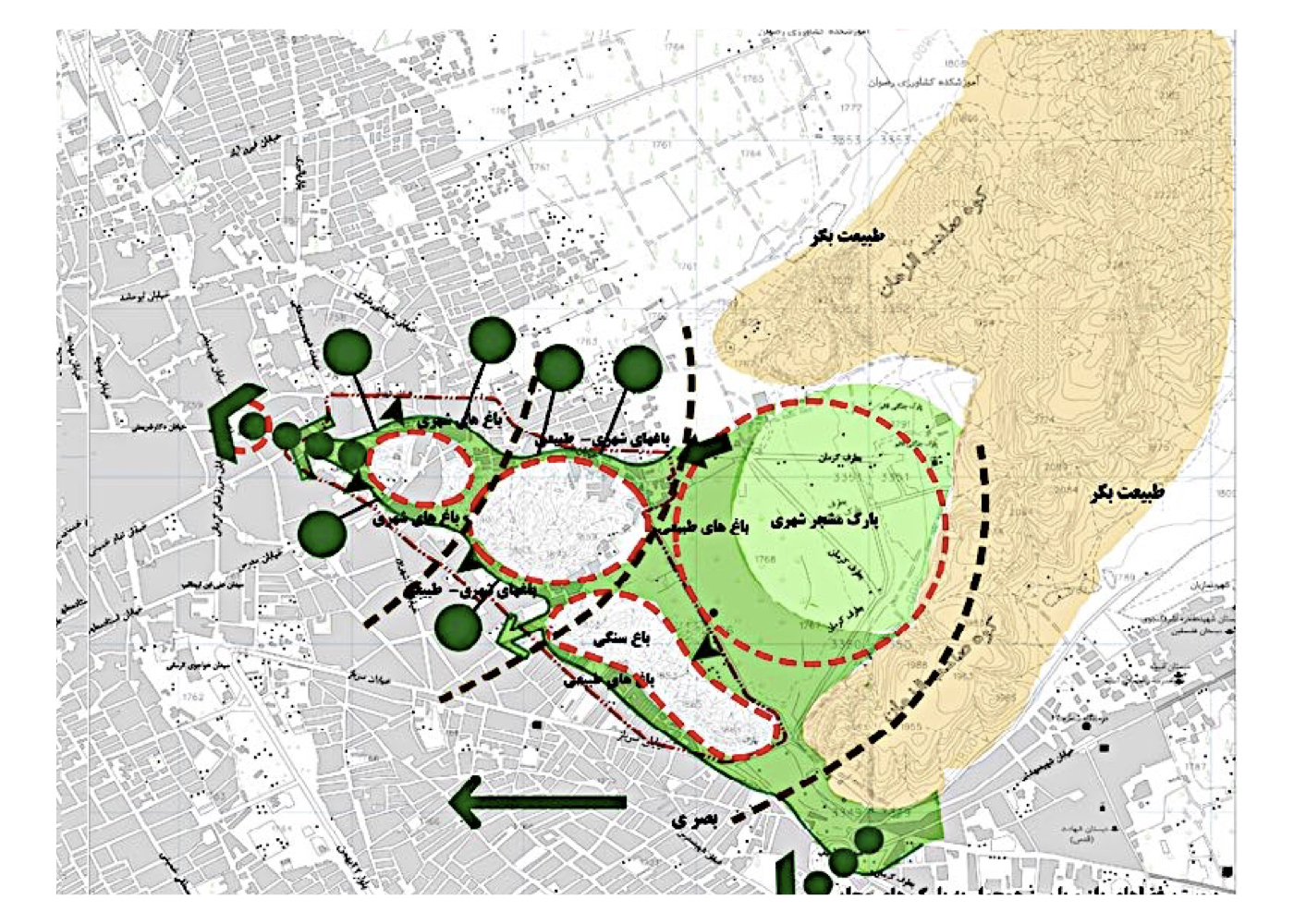

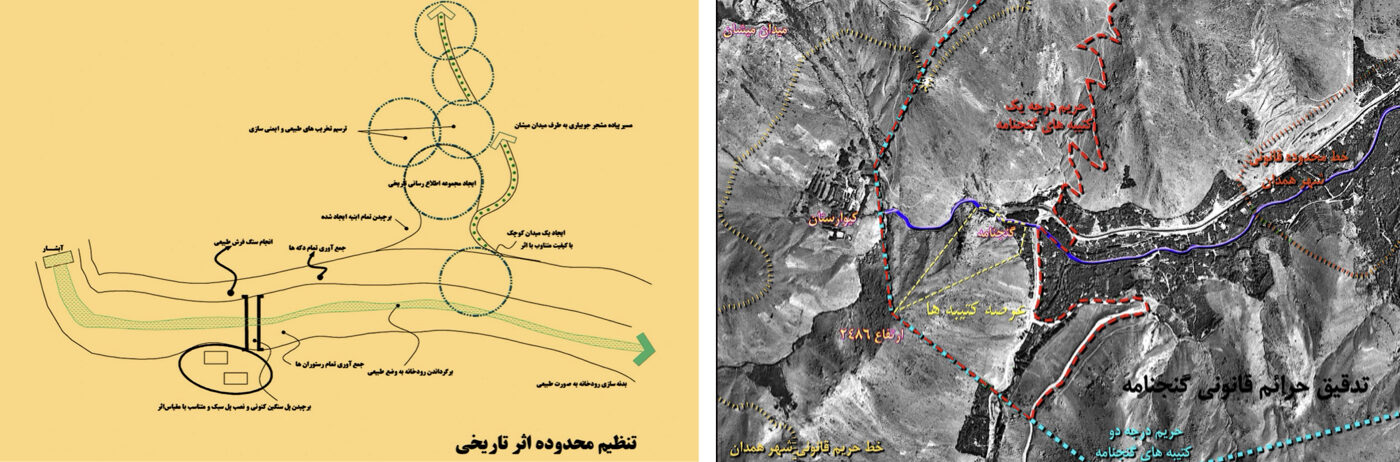

Urban – Environmental Design of Soffeh Mountain

Preventing the Degradation of Soffeh and Transforming It into a Future Natural–Historical Landmark of Isfahan

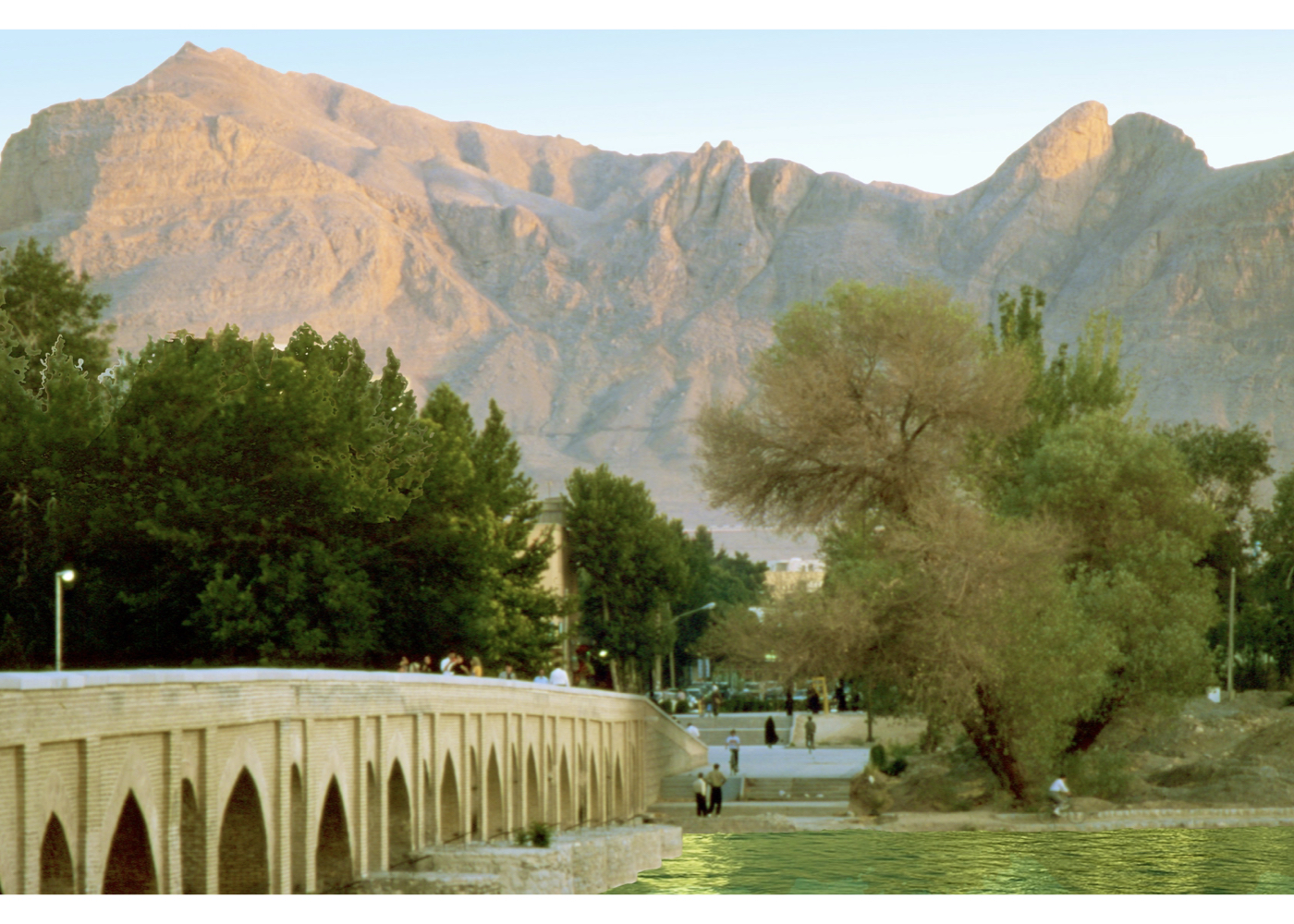

Soffeh Mountain is located in the southern part of Isfahan and is composed of a series of interlinked elevations arranged in a circular formation.

At the summit lie the remains of a military fortress, likely dating back to the Sassanid era.

This mountain and its fortress have historically played a critical role in securing the central region of the country.

Below the summit lie Zard Spring, a grove of plane trees, and architectural remnants from the Safavid period originally built for royal retreat and hospitality, symbolizing the longstanding cultural connection between the people of Isfahan and this natural recreational area.

In recent decades, the lands surrounding the mountain have been under military control, and the mountain’s slope was reportedly used as a firing range.

The Southern Ring Highway passes between the city and the mountain, severing the traditional pedestrian access and introducing safety hazards while imposing a full spectrum of pollution—light, noise, air, and social insecurity—onto this valuable natural environment.

Key Strategies and Interventions:

1. Realign the western segment of the Southern Ring Highway, which currently disrupts safe pedestrian access to Soffeh.

2. Designate an alternative highway route south of the mountain.

3. Convert the decommissioned highway segment into a recreational corridor to facilitate safe public access between the city and Soffeh.

4. Cancel the cable car project at the contractor’s proposed site and relocate it to the former firing range.

5. Reassign the firing range for tourism and recreational development.

6. Construct the cable car terminal outside the protected zone of Shah-Dezh Fortress and at a lower elevation.

7. Implement rockfall mitigation and safety upgrades on hiking trails prone to landslides.

8. Revitalize Shah-Dezh Fortress into a 24-hour facility for hospitality, lodging, and mountaineering recreation.

9. Develop a nature-based sports complex in the northeastern lands of Soffeh.

10. Establish a protected wildlife reserve in the flatlands between the mountain ridges, covering approximately 200 hectares.

11. Create pedestrian, cycling, and tourist carriage routes connecting Soffeh to Zayandeh-Rood (Najvan) via perpendicular urban streets.

12. Restore road damage near Pachnar Spring (as the first implemented strategic measure).

Note:

The plan was approved, and item 12 was partially executed. Unfortunately, the remaining strategies were not implemented, and the cable car was constructed in an unsuitable location.

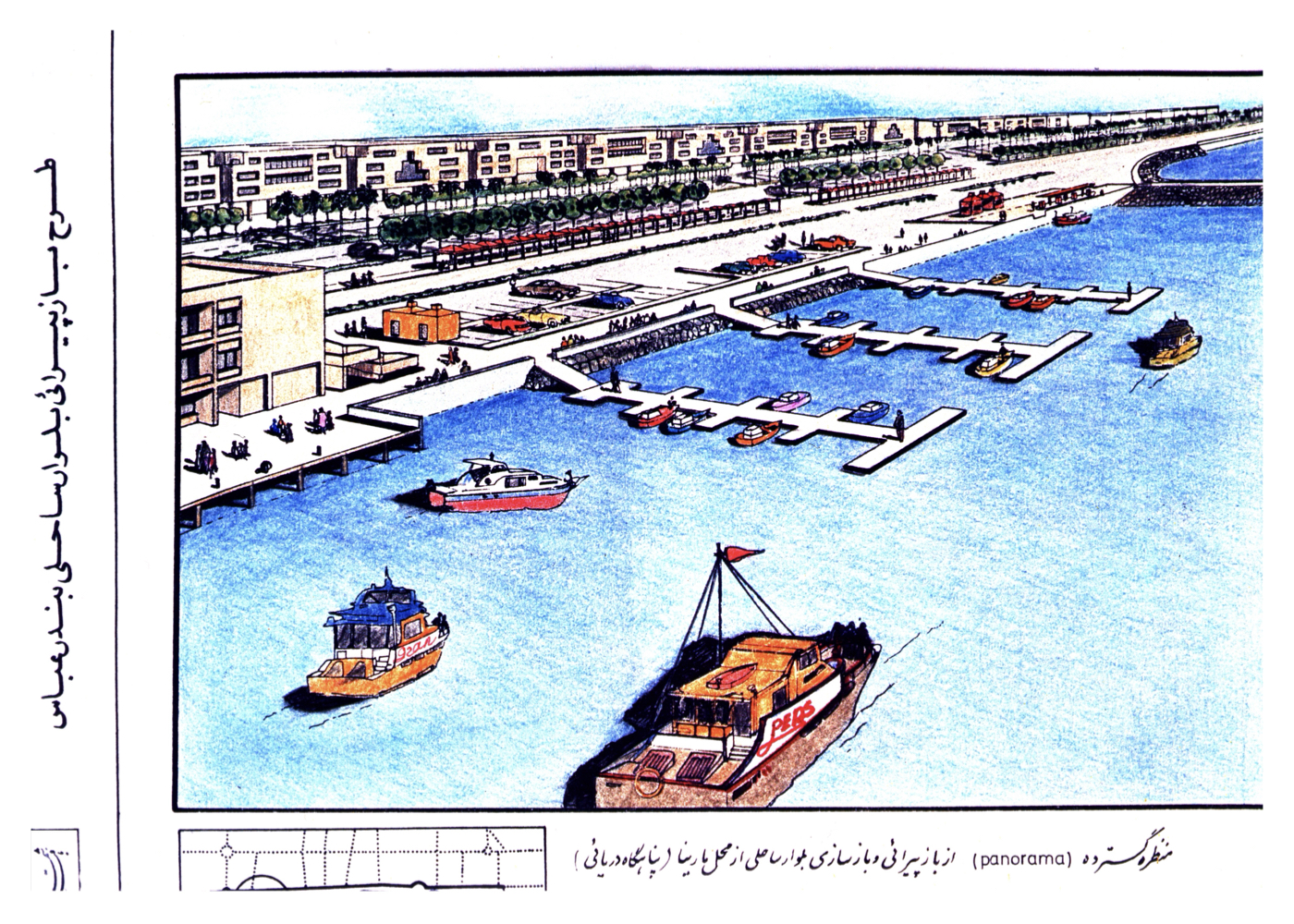

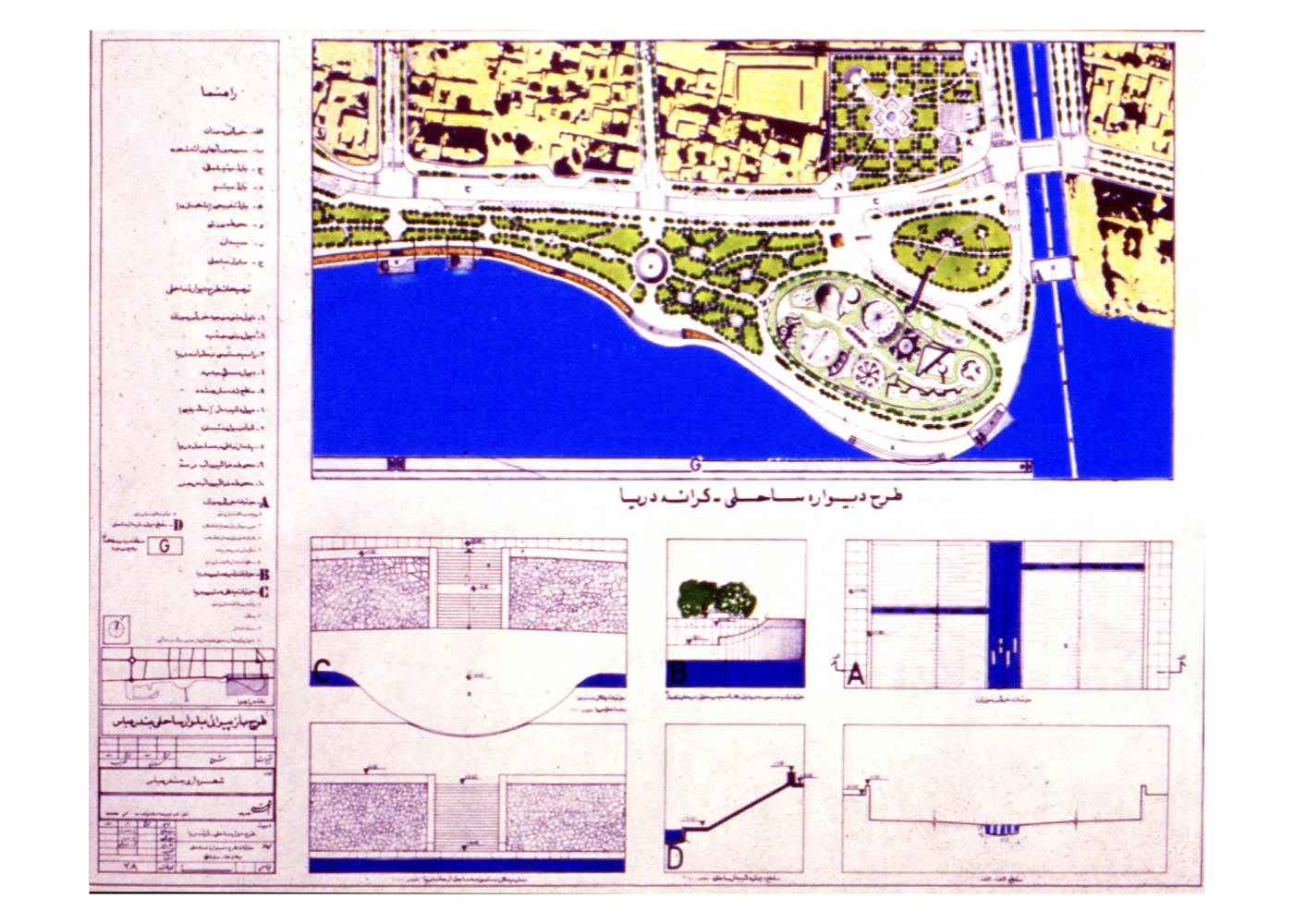

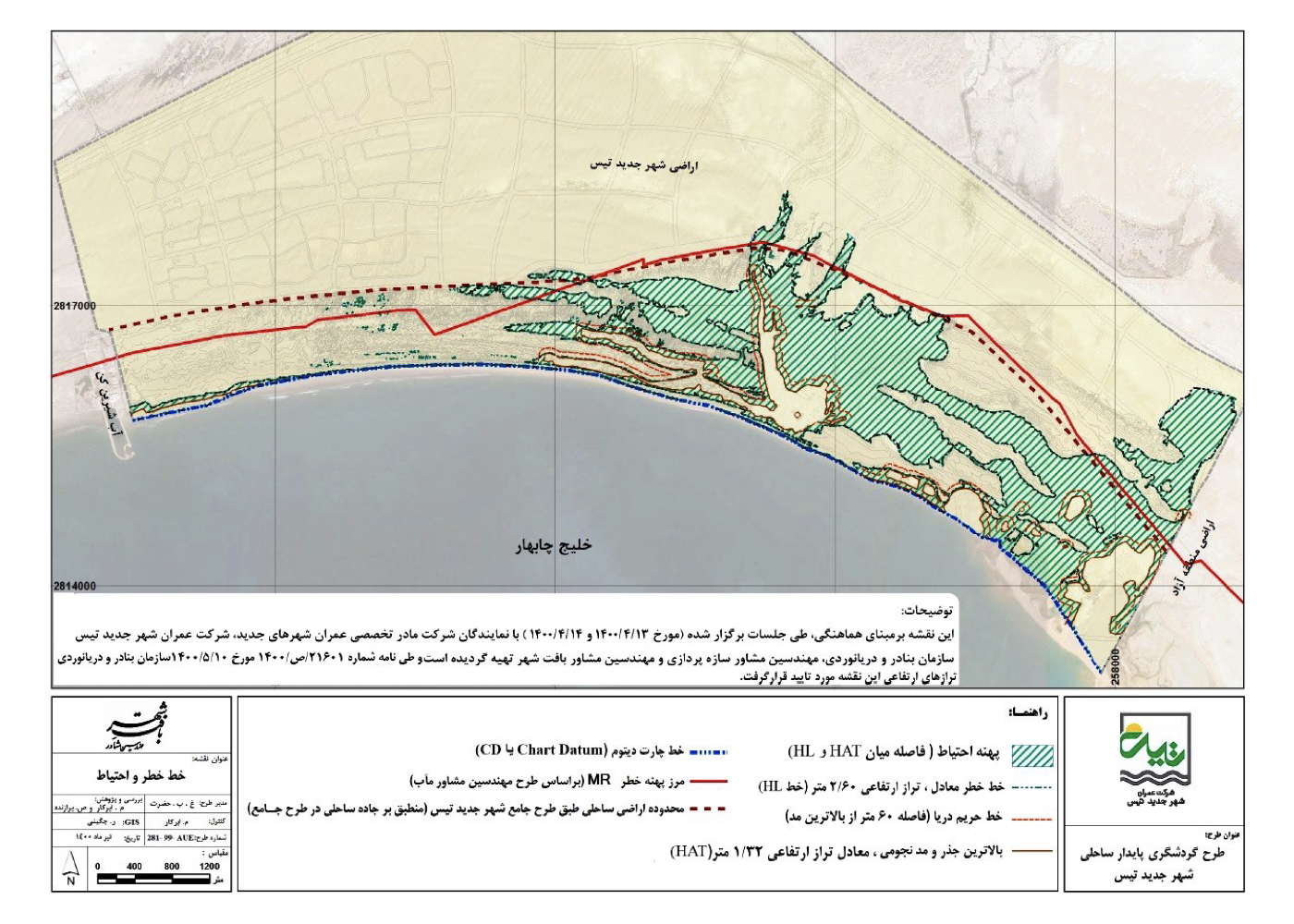

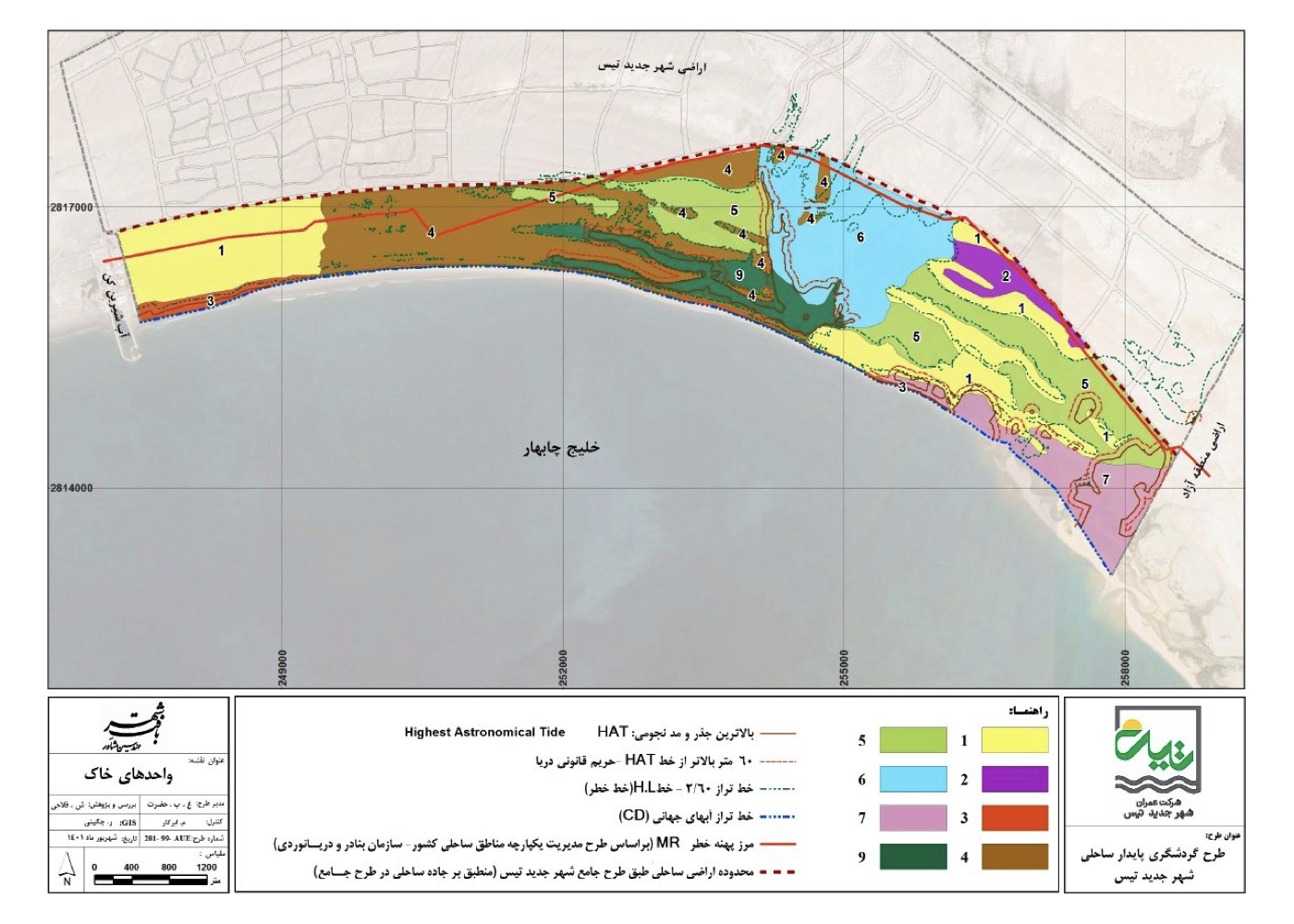

BANDAR ABBAS

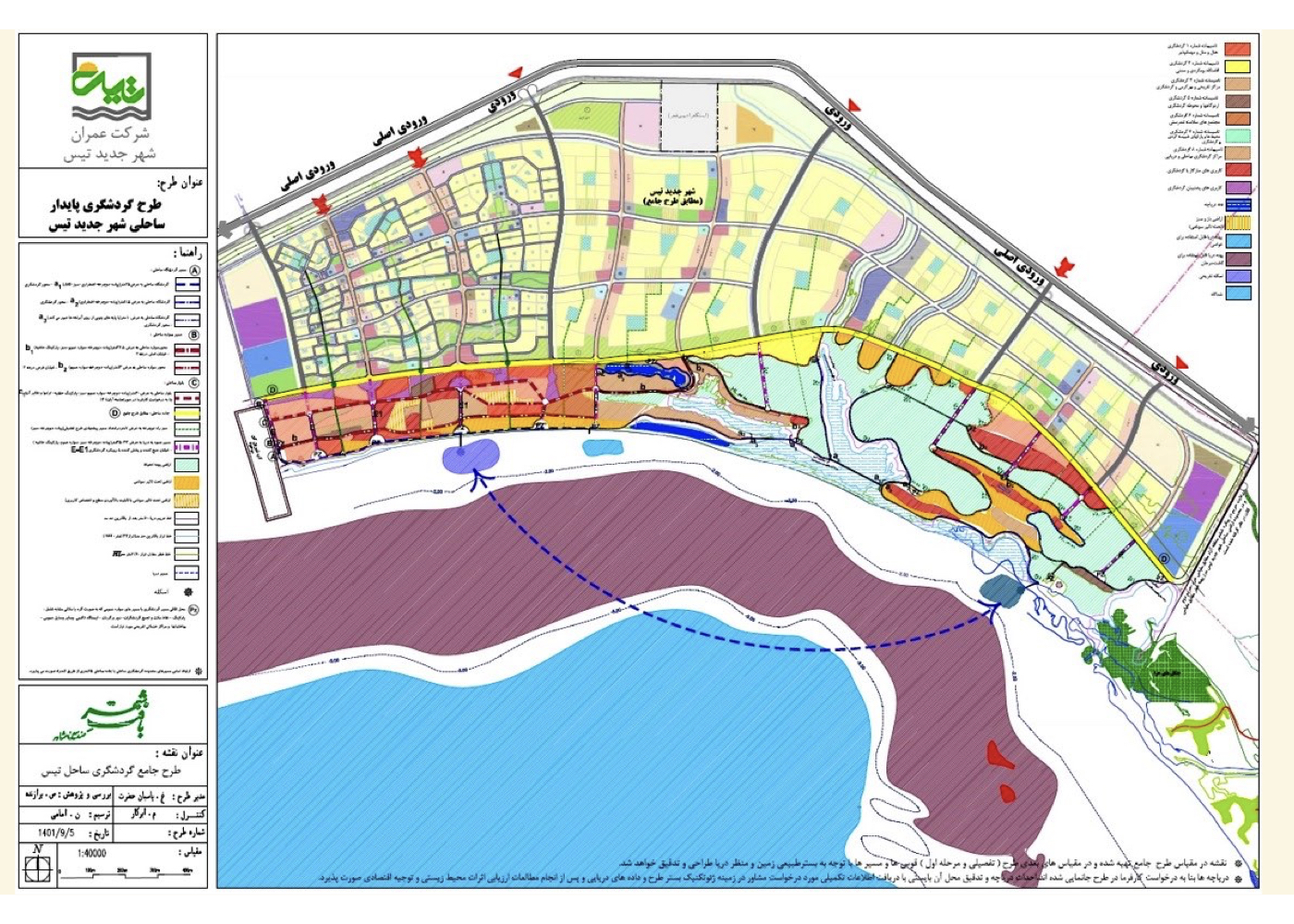

Coastal Boulevard Project (Phase One)

Summary of Proposal:

Preventing further coastal degradation, protecting urban infrastructure, and enhancing environmental quality and tourism services in the city.

Background:

In the 1960s, a coastal boulevard was constructed in front of the city’s historic center to organize the shoreline. A stone retaining wall was built along part of the boulevard to reinforce it, but throughout the 1980s, it was repeatedly damaged by waves and repaired. In addition to this, the green space of the boulevard, the fish market, customs facilities, street vendors, substance users, dilapidated structures, and poor visual appearance—combined with a lack of tourism infrastructure, were among the major issues affecting this coastal section.

The client initially requested a landscape design for the coastal greenery, but it became clear that more critical problems had to be addressed beforehand. Despite a lack of reliable data on sea conditions, waves, and tides, various studies were conducted, resulting in a design proposal for a 2,500-meter coastal segment (from the fish market to Khor-e Gūr Sūzān).

Summary of Existing Conditions:

1. The existing coastal wall protects the boulevard and its green spaces from wave action.

2. The wall is continuously damaged by wave impact.

3. Ongoing destruction of green areas, disorder around the fish market and boat traffic, vagrants and substance users, visual pollution, and lack of tourist amenities are major issues.

4. Rising water levels near Khor-e Gūr Sūzān are due to blocked drainage systems.

Summary of Ideas and Solutions:

1. Design of a marina (protected basin) for boats and ships at the former Gambron Port and its integration with transport infrastructure

2. Using the marina to regulate maritime traffic and buffer wave energy affecting the shoreline

3. Building a new concrete retaining wall and installing wave breakers at vulnerable points

4. Removing the old customs buildings and dilapidated pier, and repurposing protruding land areas

5. Developing a commercial–administrative complex on the reclaimed land

6. Technical improvements to the drainage walls of Khor-e Gūr Sūzān to prevent underground water infiltration

7. Designing climate-appropriate green spaces

8. Transforming the coastal boulevard into a linear coastal park

9. Developing a coastal visual identity plan that aligns with local architecture and proposed land uses

10. Aligning the plan with upper-tier comprehensive and detailed plans, and adapting it to the local environmental context

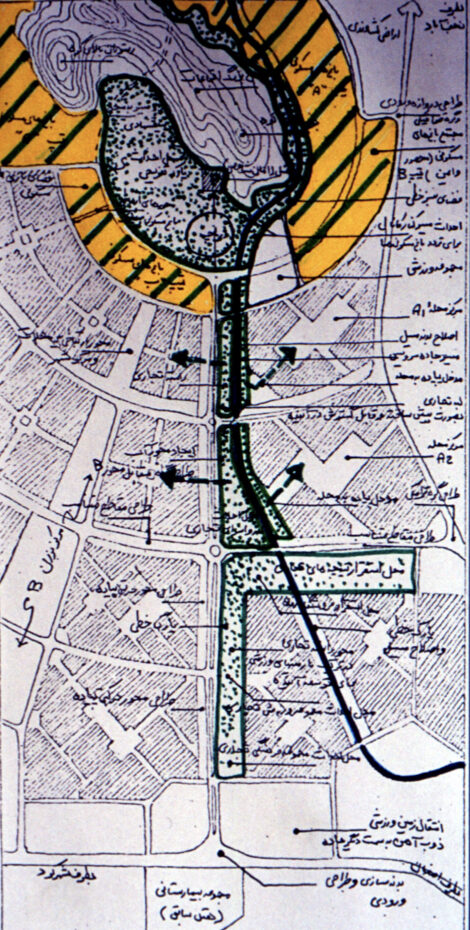

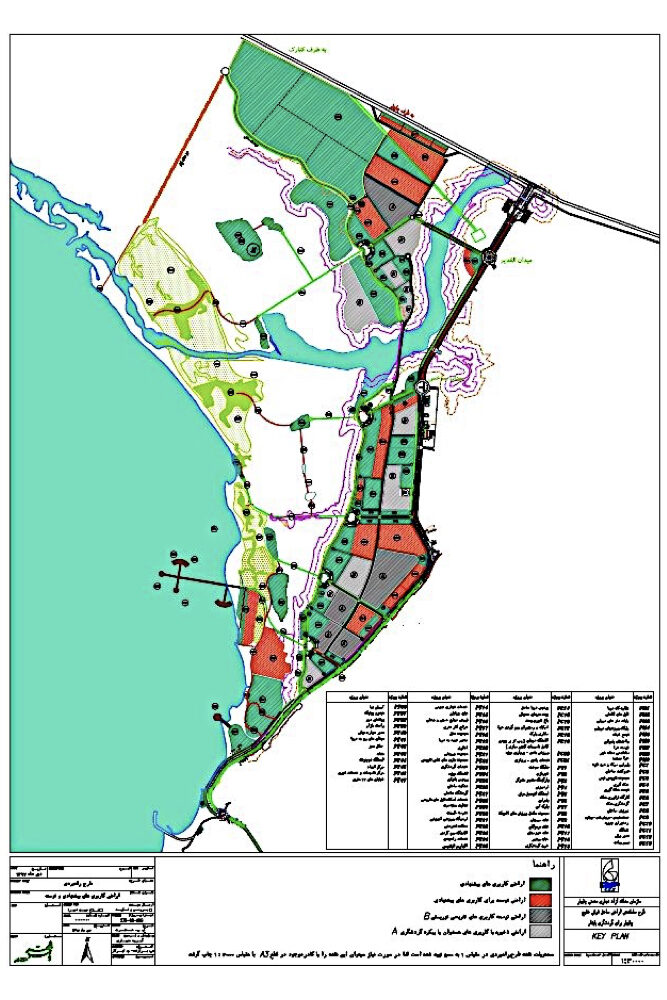

Poladshahr

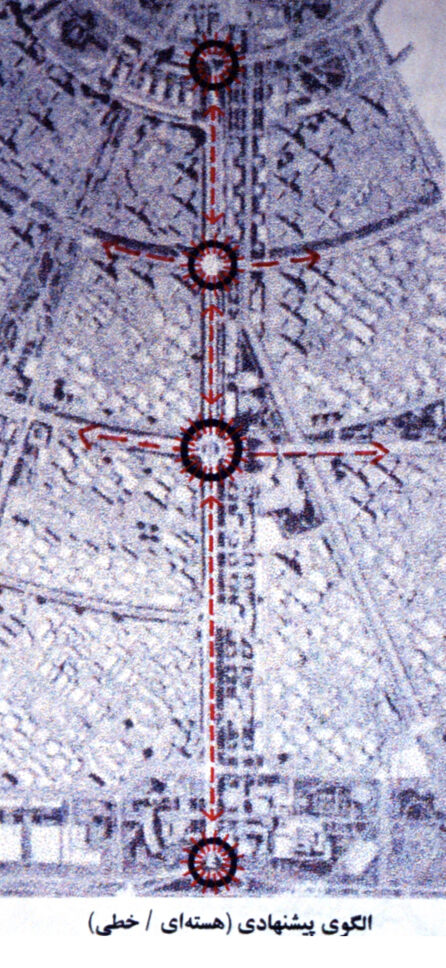

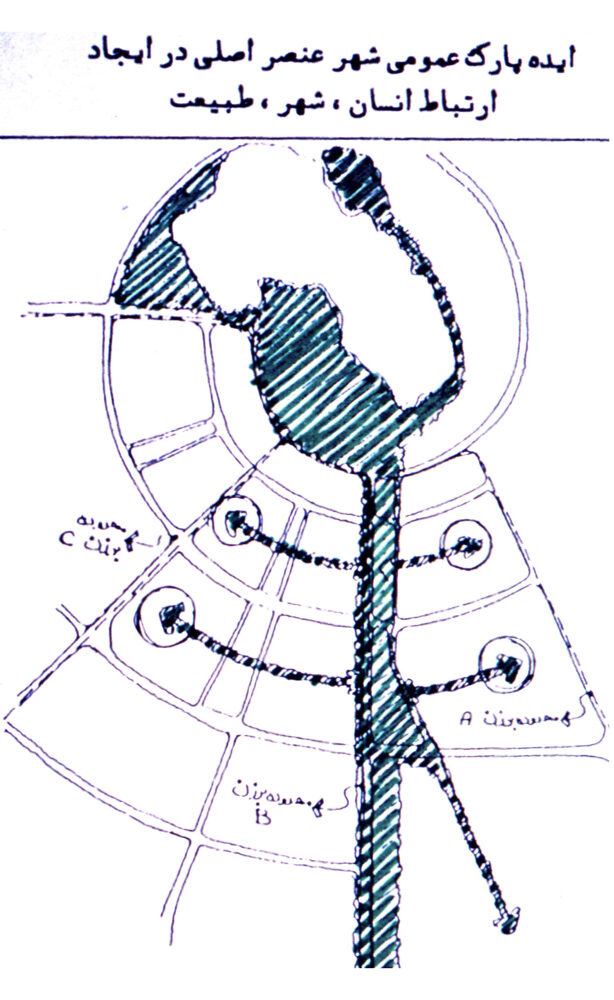

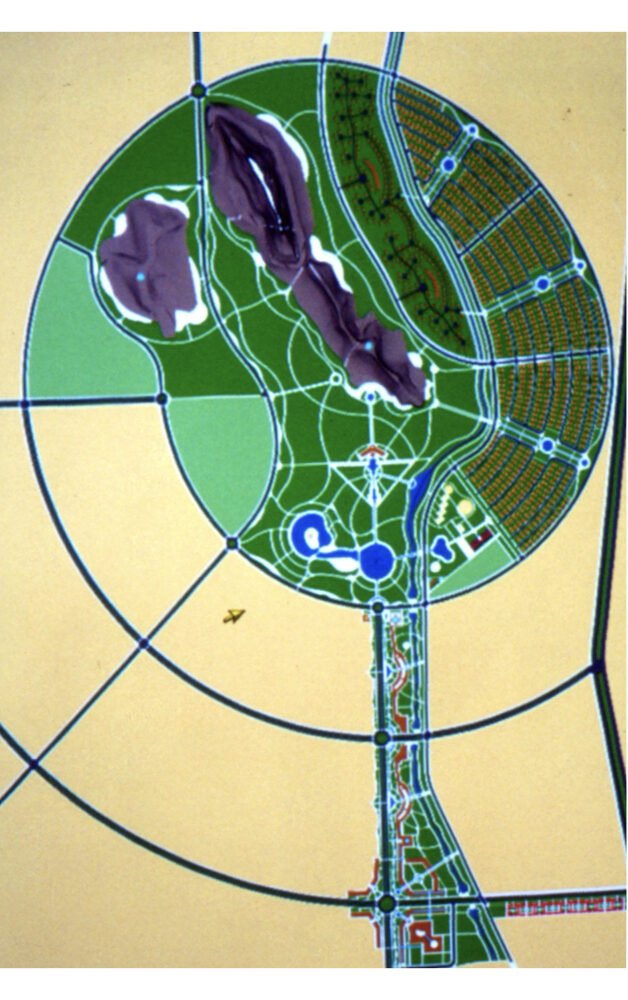

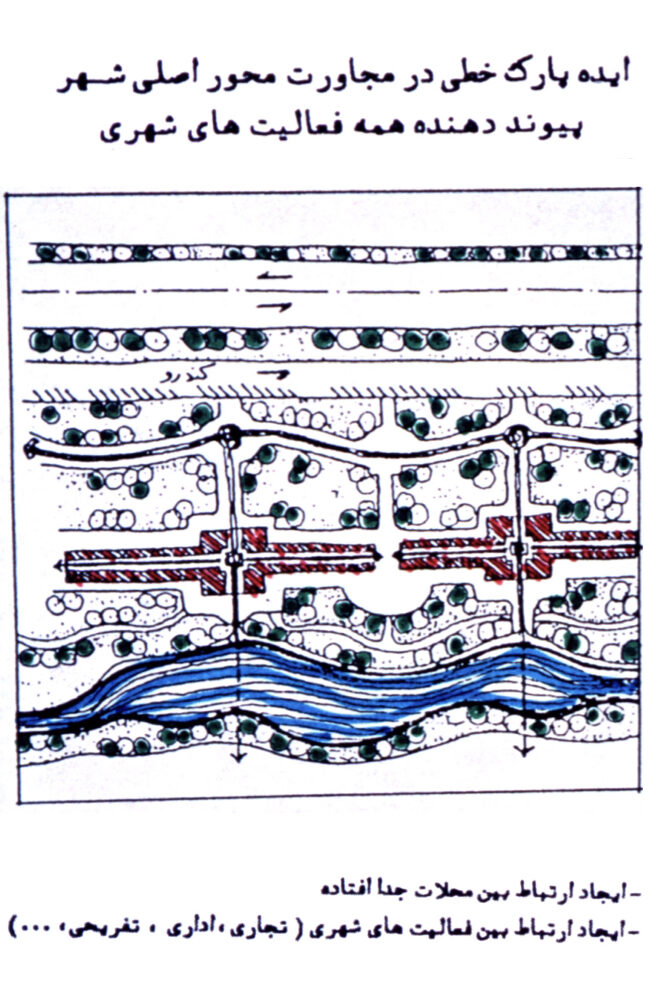

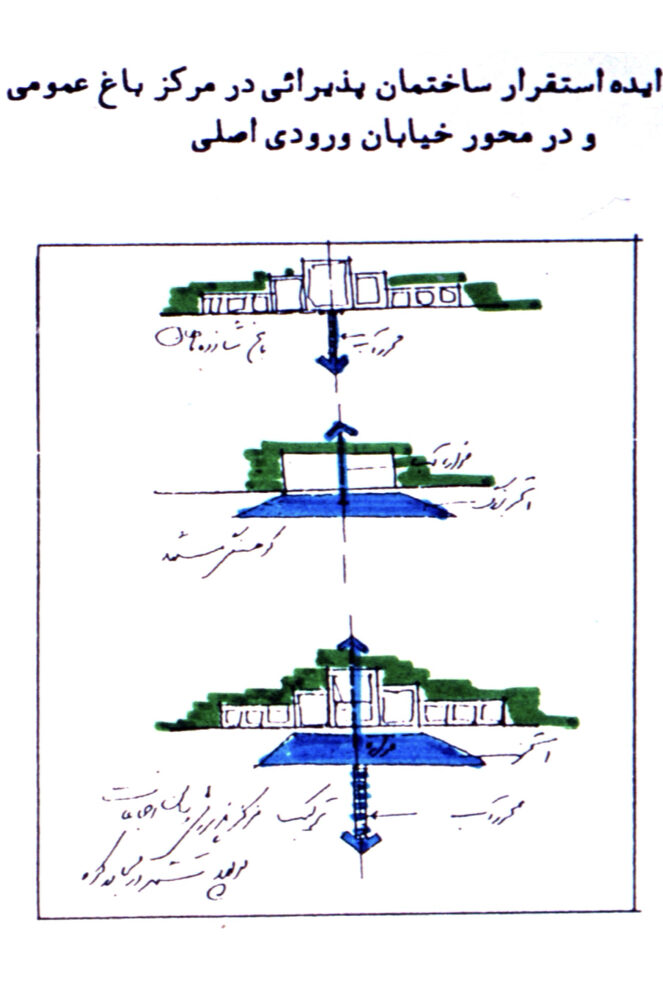

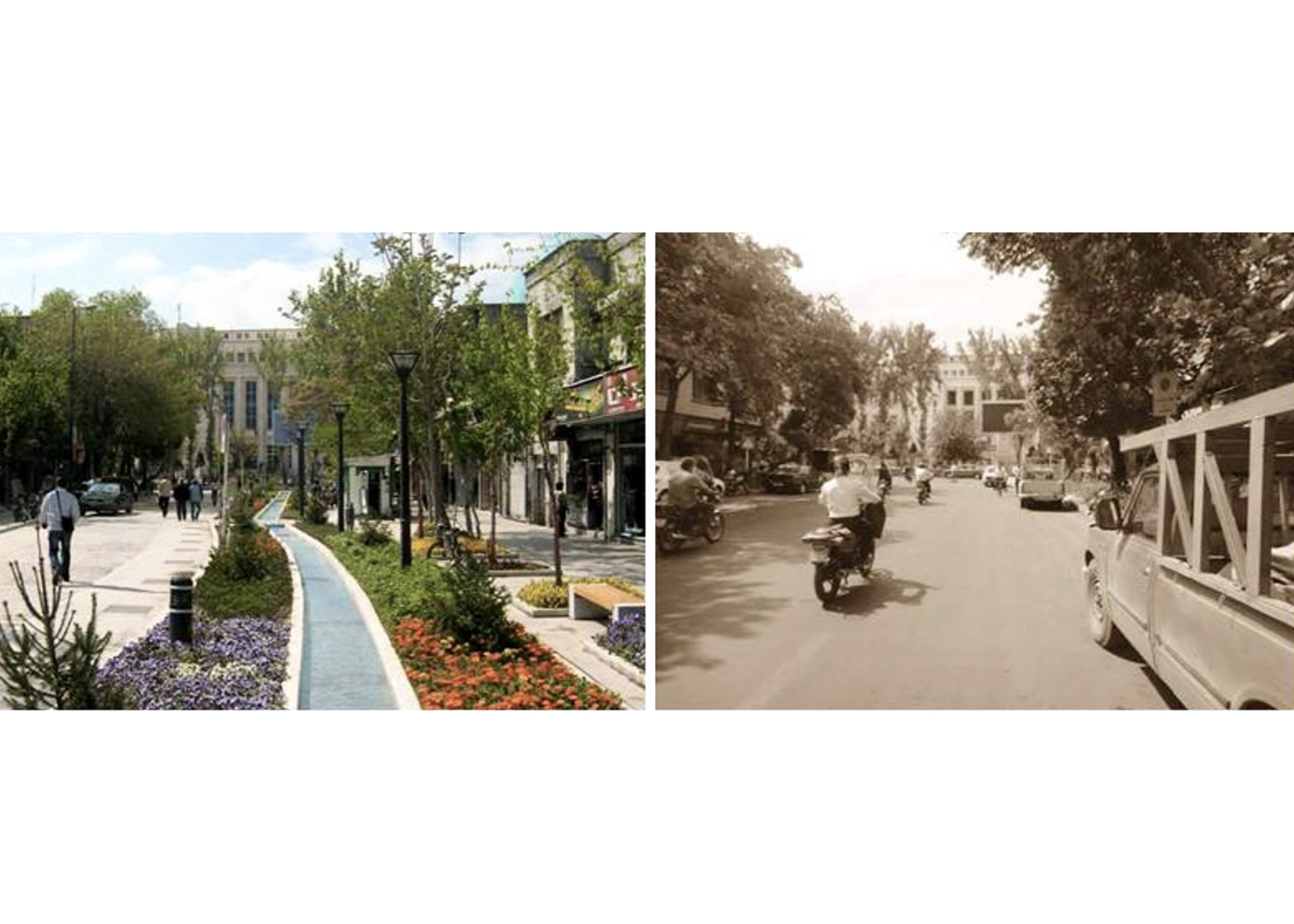

Urban – Environmental Design of the City’s Central Axis

Summary of Proposal:

Enhancing the environmental quality of the city’s central service corridor by strengthening its connection to the adjacent natural landscape (mountain).

Background:

Poladshahr is a newly planned city located 20 kilometers from Isfahan, originally designed to house employees of the Isfahan Steel Plant, and is gradually expanding. The project area is the city’s main urban axis, which extends toward the nearby hills. This project was part of an urban design competition, where the consultant secured second place by a narrow margin. The client proposed a joint effort with the first-place winner, but the consultant declined.

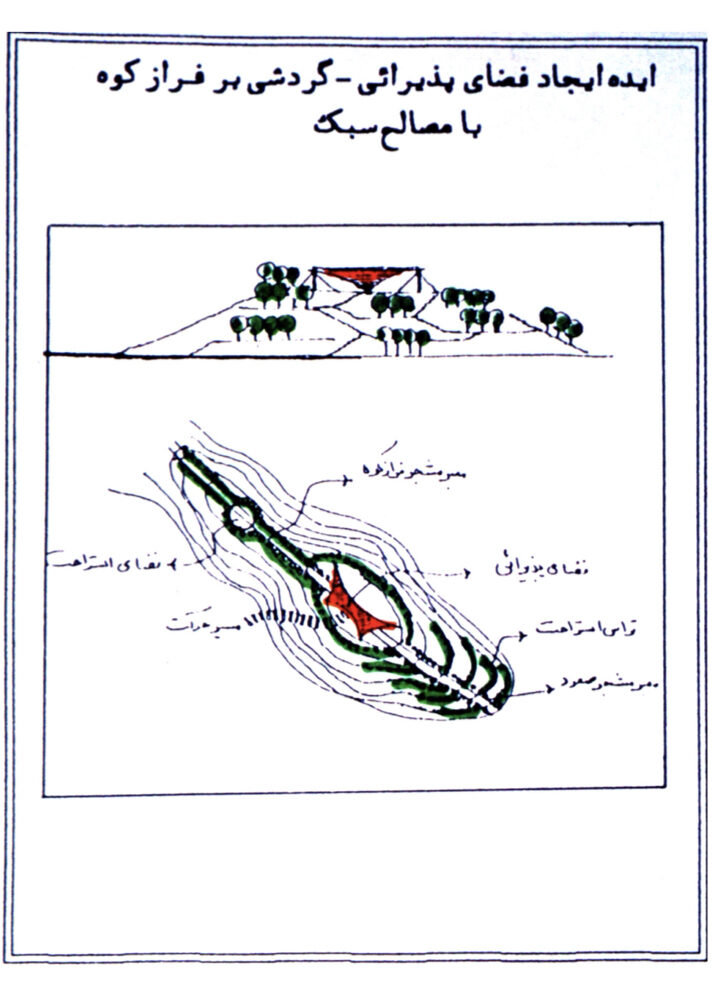

Summary of Core Concepts Based on Isfahan’s Climatic and Cultural Characteristics:

1. Guiding surface water flow along pedestrian walkways by transforming hazardous water channels into tranquil, stream-like features

2. Establishing strong, shaded green corridors along pedestrian paths (inspired by the historic Chaharbagh axis)

3. Extending the green corridor to the mountain summit to connect urban and natural environments via a continuous green belt

4. Reinforcing physical and functional connectivity between the city and mountain through a tree-lined pedestrian spine

5. Creating a large public terrace with cultural and recreational facilities atop the mountain as a gathering and interaction node

6. Constructing a hospitality structure next to the terrace for day-and-night use by residents and tourists

7. Designing a public linear “urban paradise” (interlinked gardens) at the junction of urban fabric and foothills

Final Vision of the Plan:

Poladshahr would feature a linear green-commercial center with a stream, an urban paradise at the base of the mountain, a green, ecologically restored mountain, and a vibrant natural space for public interaction and recreation—day and night.

tehran

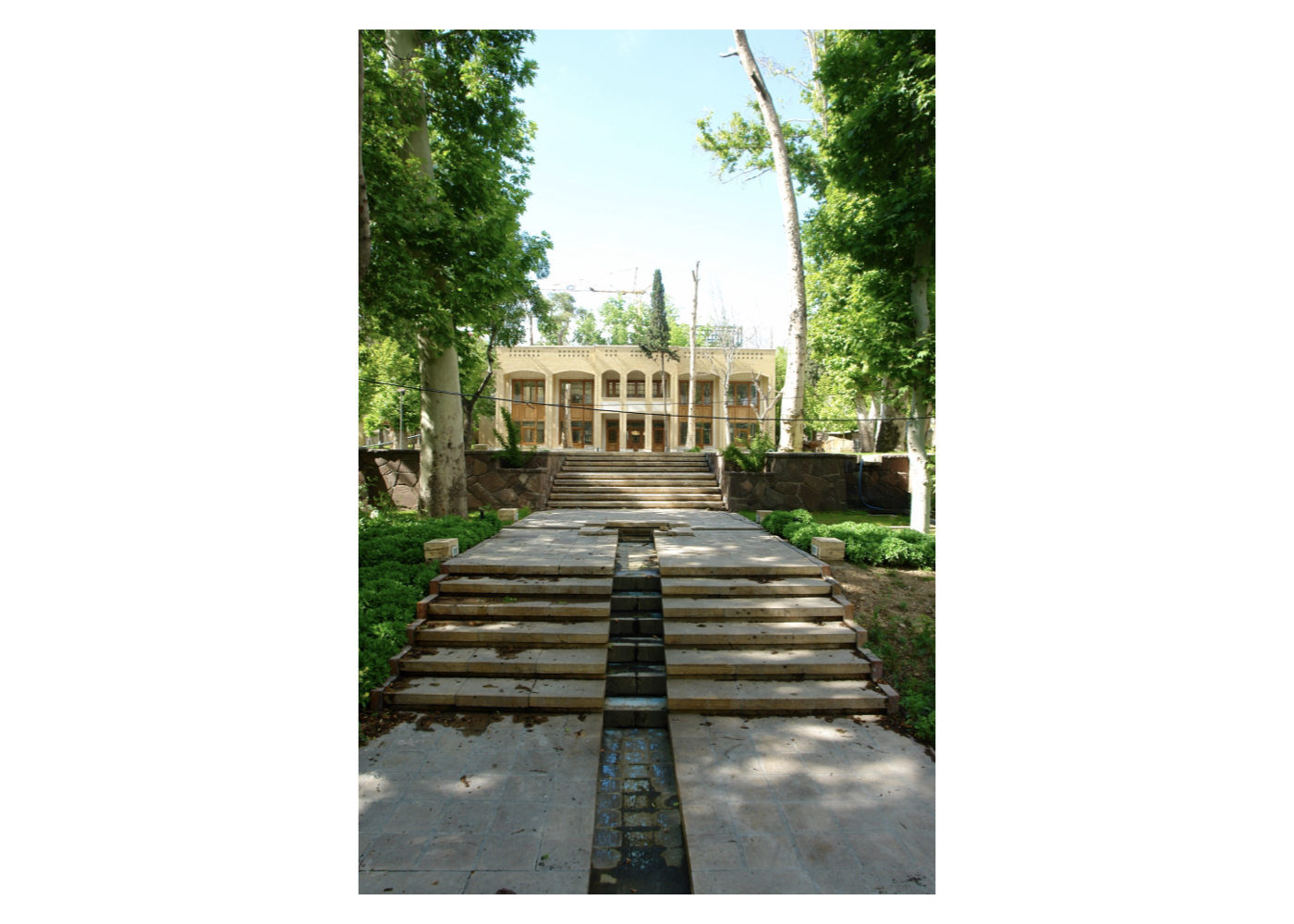

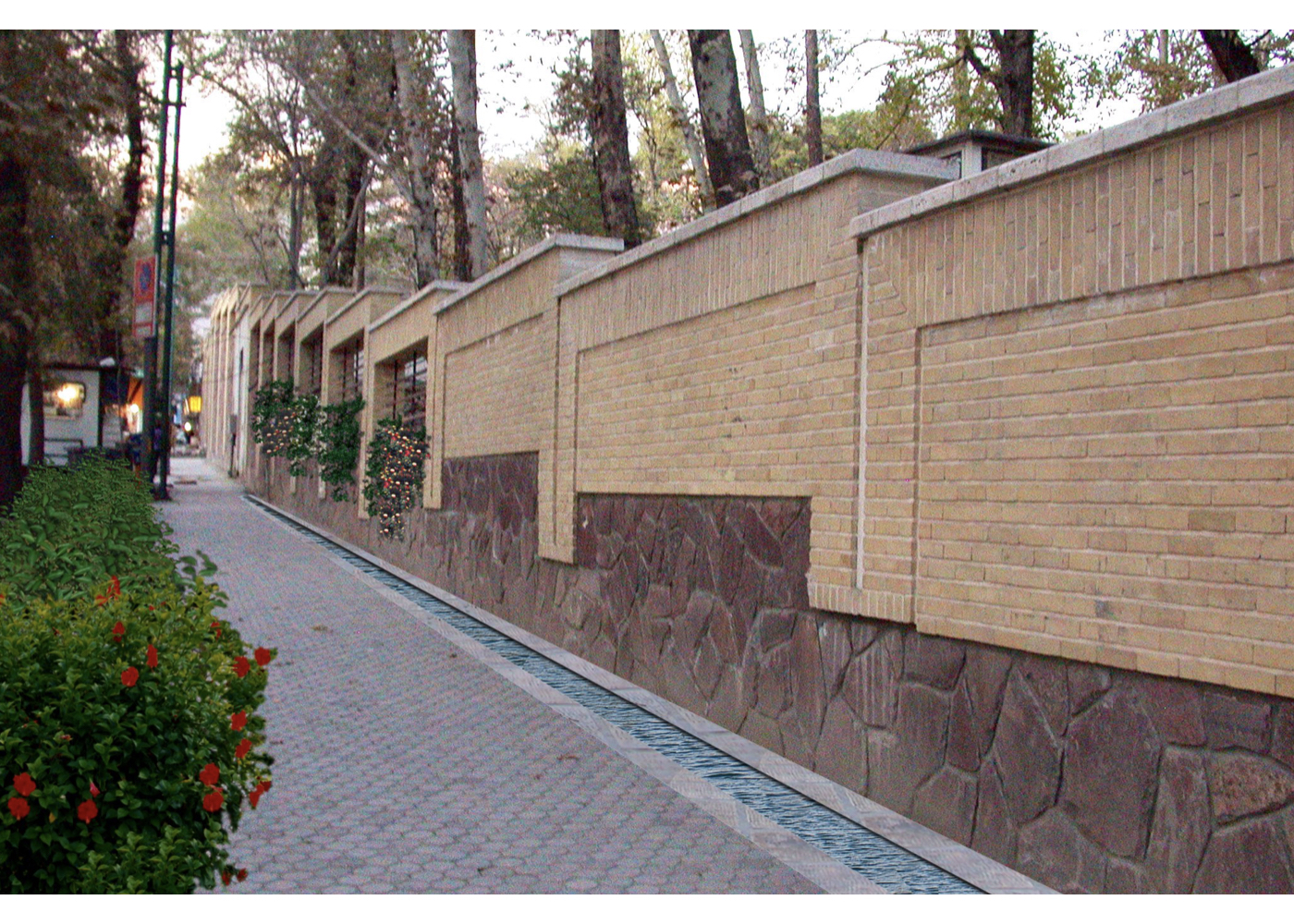

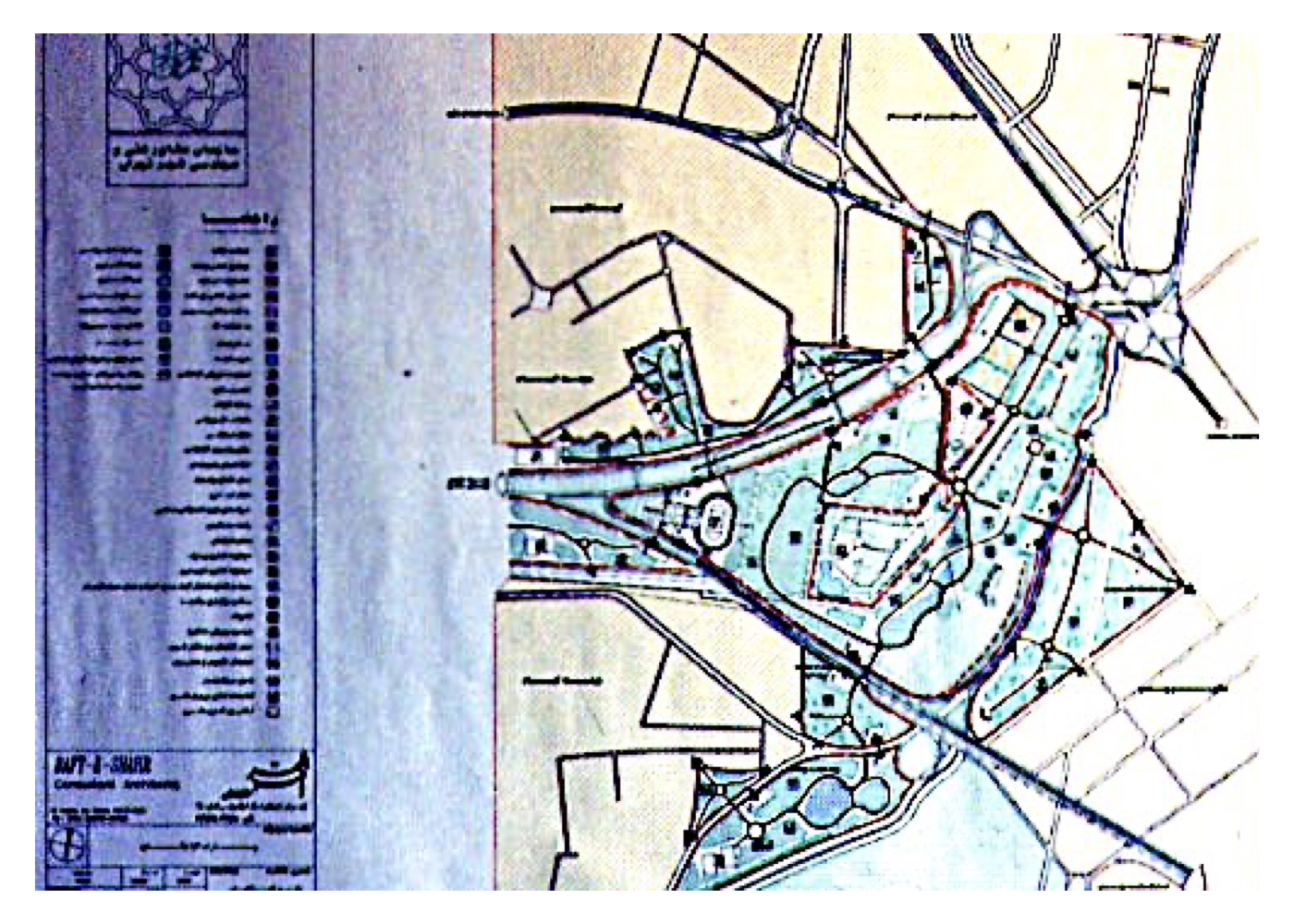

Urban – Environmental Design of the National Oil Company Garden

Summary of Proposal:

Preventing the gradual destruction of a historic garden and its qanat by designing an educational–hospitality complex for the National Oil Company

Background:

This small garden, which contained a qanat (traditional underground aqueduct), mature trees, and an unstable structure, belonged to the National Iranian Oil Company.

In initial negotiations, it was agreed that the garden’s function would be redirected to activities aligned with the company’s needs. Following preliminary studies and in a meeting with the then Minister of Oil, the educational–hospitality use was selected as the most viable option to ensure the garden’s preservation.

Designated Functional Objectives:

1. Hosting guests of the National Oil Company

2. Providing training for company managers

3. Holding contract signings and official meetings

The proposal included:

1. Landscape restoration of the garden

2. Revitalization of the qanat and its emergence point

3. Structural reinforcement and architectural enhancement of the existing building

4. Construction of a new hospitality facility

5. Building a training center and conference hall

6. Provision of appropriate parking facilities

Important Note:

This project exemplifies how a compatible new use can align with the ecological and spatial capacity of a historic garden, where ownership by a stable and reputable institution enables both protection and maintenance funding.

Unfortunately:

After the plan’s completion, Tehran Metro Company constructed a station along the qanat route without coordination, disrupting the qanat’s flow and compromising its function.

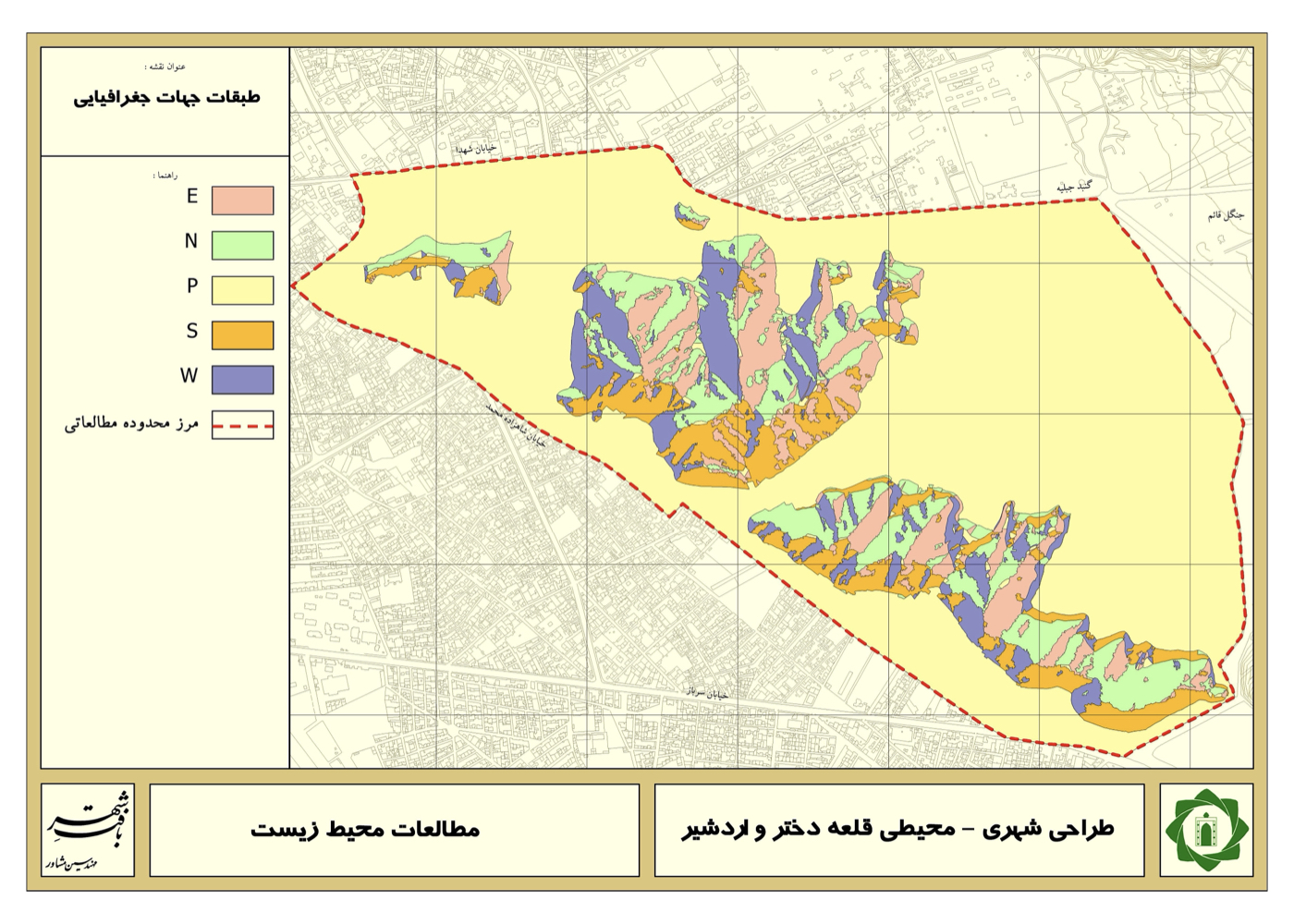

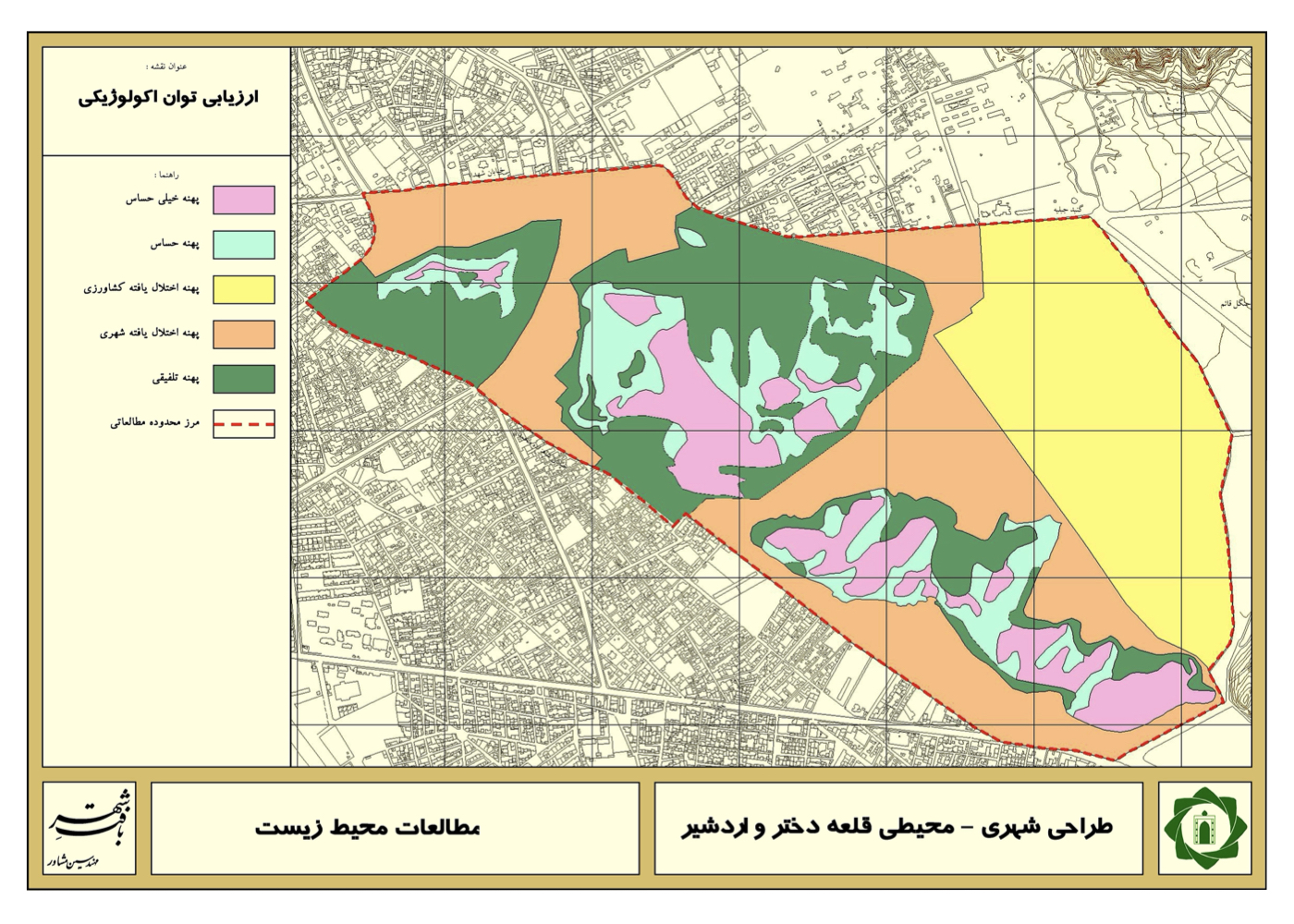

Plan for the Protection and Regeneration of Gardens and Farmlands (Strategic)

Summary of Proposal:

Formulating environmental policies and planning strategies for conserving and organizing gardens and farmlands, based on ecological zoning and environmental baseline studies.

Background:

Since the 1960s, protecting urban gardens has been an ongoing challenge for municipalities in cities like Tehran, Mashhad, Tabriz, and Shiraz. Master and detailed plans, as well as thematic studies, have largely failed to address the issue effectively.

Root Cause of Failure:

The primary failure was due to offering solutions rooted solely in urban planning without adequately integrating environmental considerations.

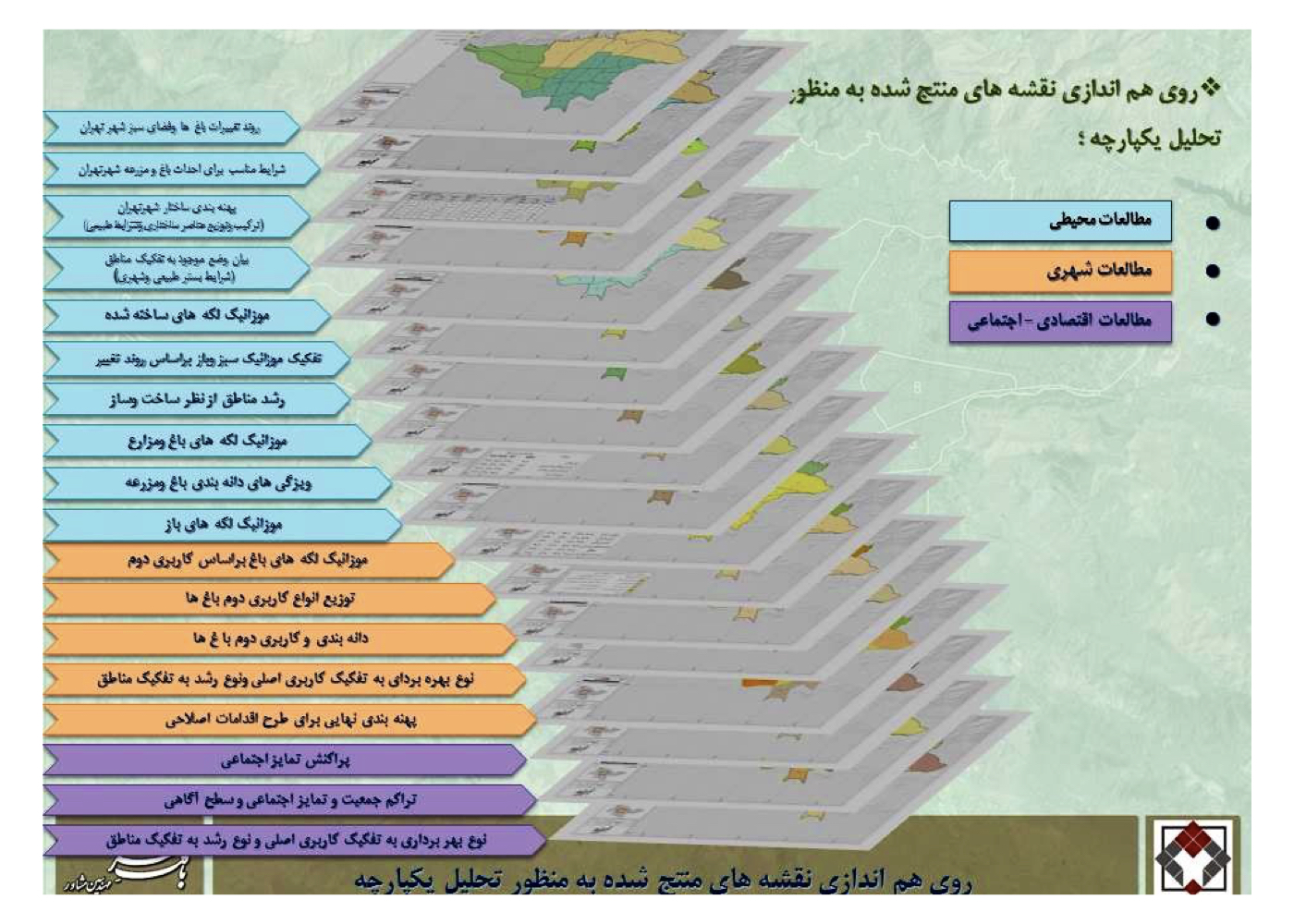

Tehran Municipality signed a contract with the Baft-E-Shahr consultant for this project and the study was structured around baseline research in:

1. Environment and landscape

2. Urban planning and legal frameworks

3. Urban economy

4. Acquired property rights and ownership

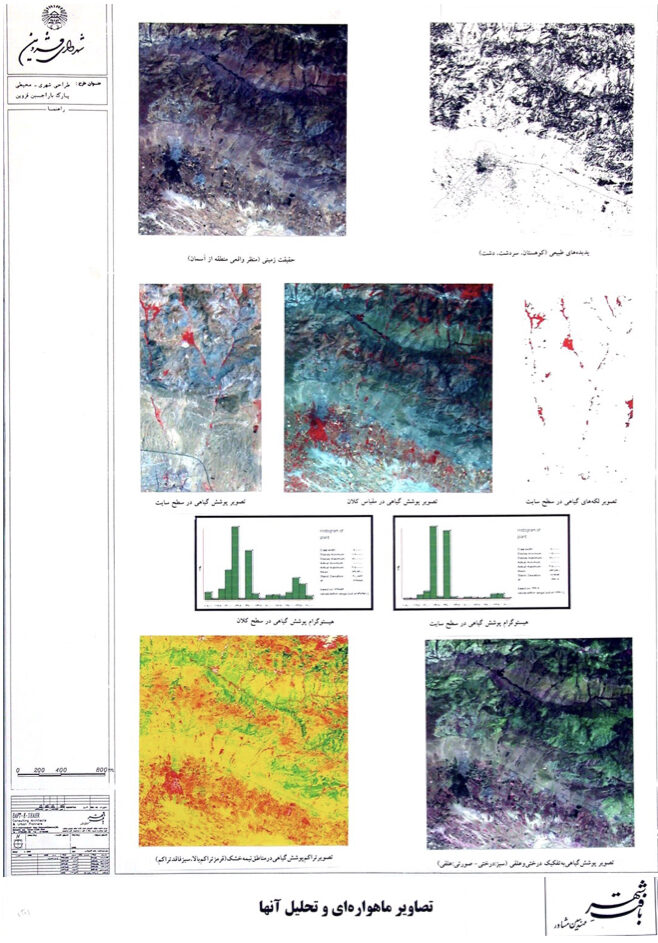

Innovative Feature of the Plan:

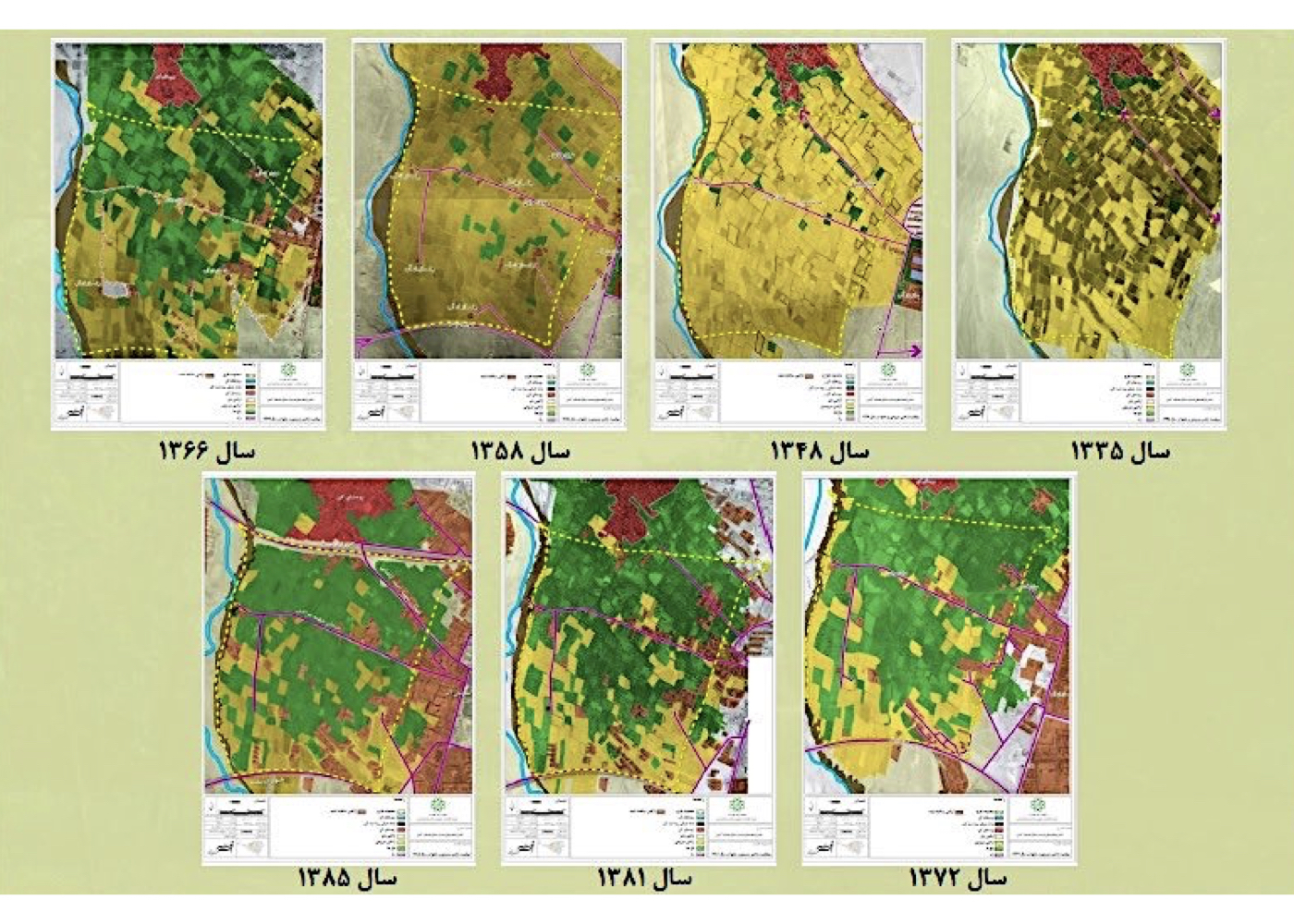

Due to the vast number and dispersion of gardens and farmlands, and the difficulty of site visits, this became the first urban planning project in Iran to employ satellite image analysis as a primary environmental and landscape study method. Satellite imagery was acquired and analyzed by experts, and the outcomes informed decisions across sectors including landscape, ecology, urban planning, and more.

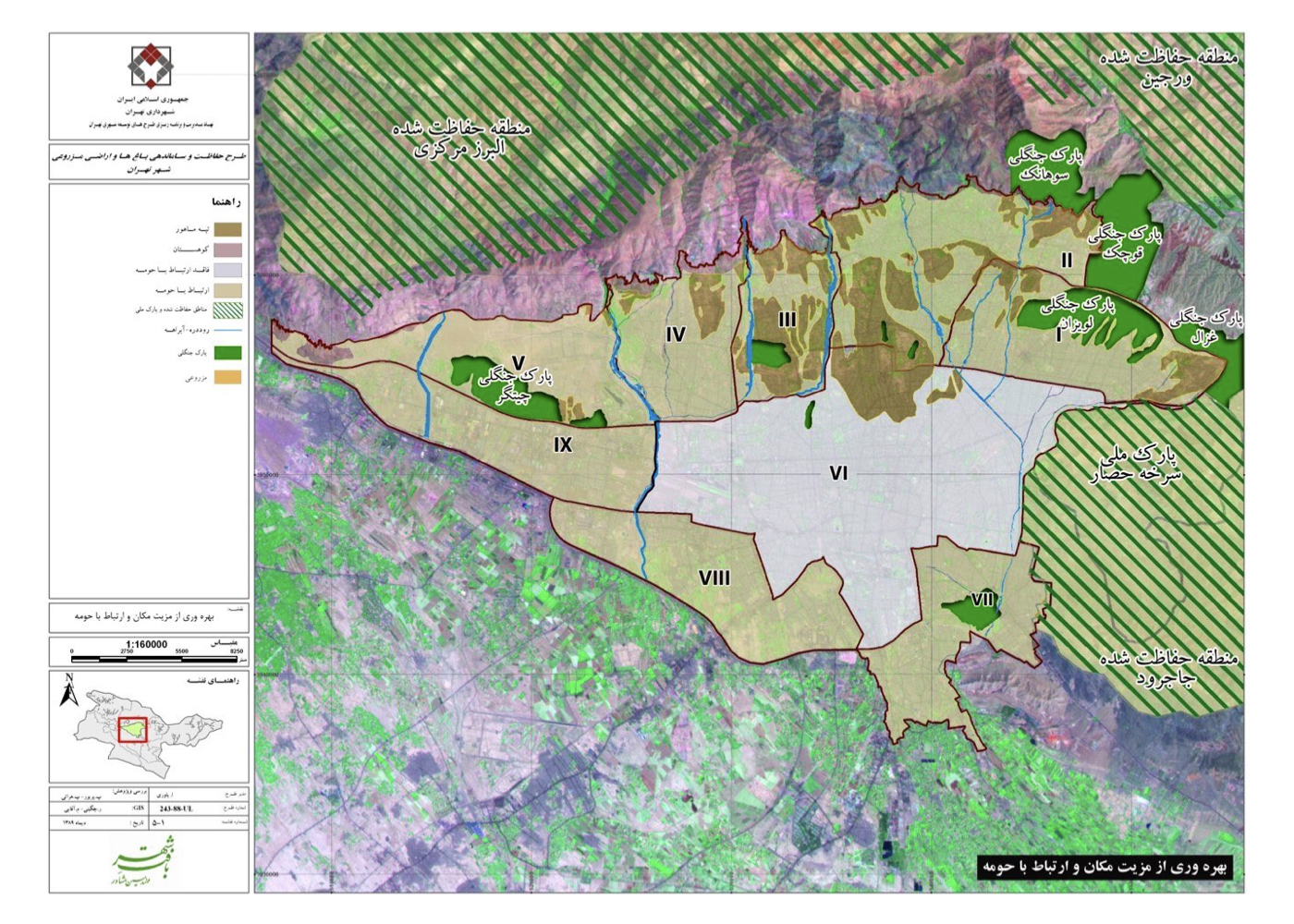

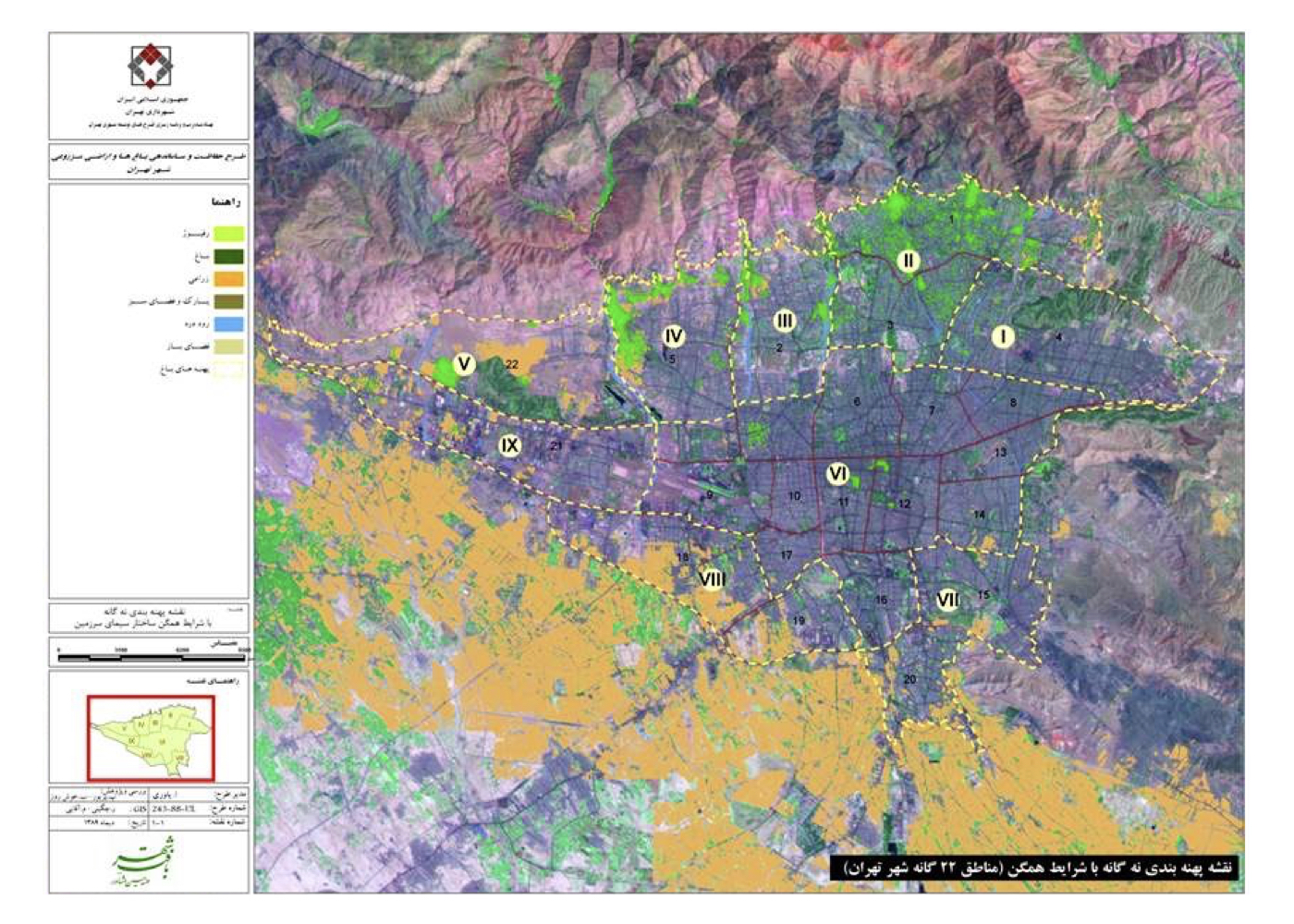

Summary of Ideas and Strategic Measures:

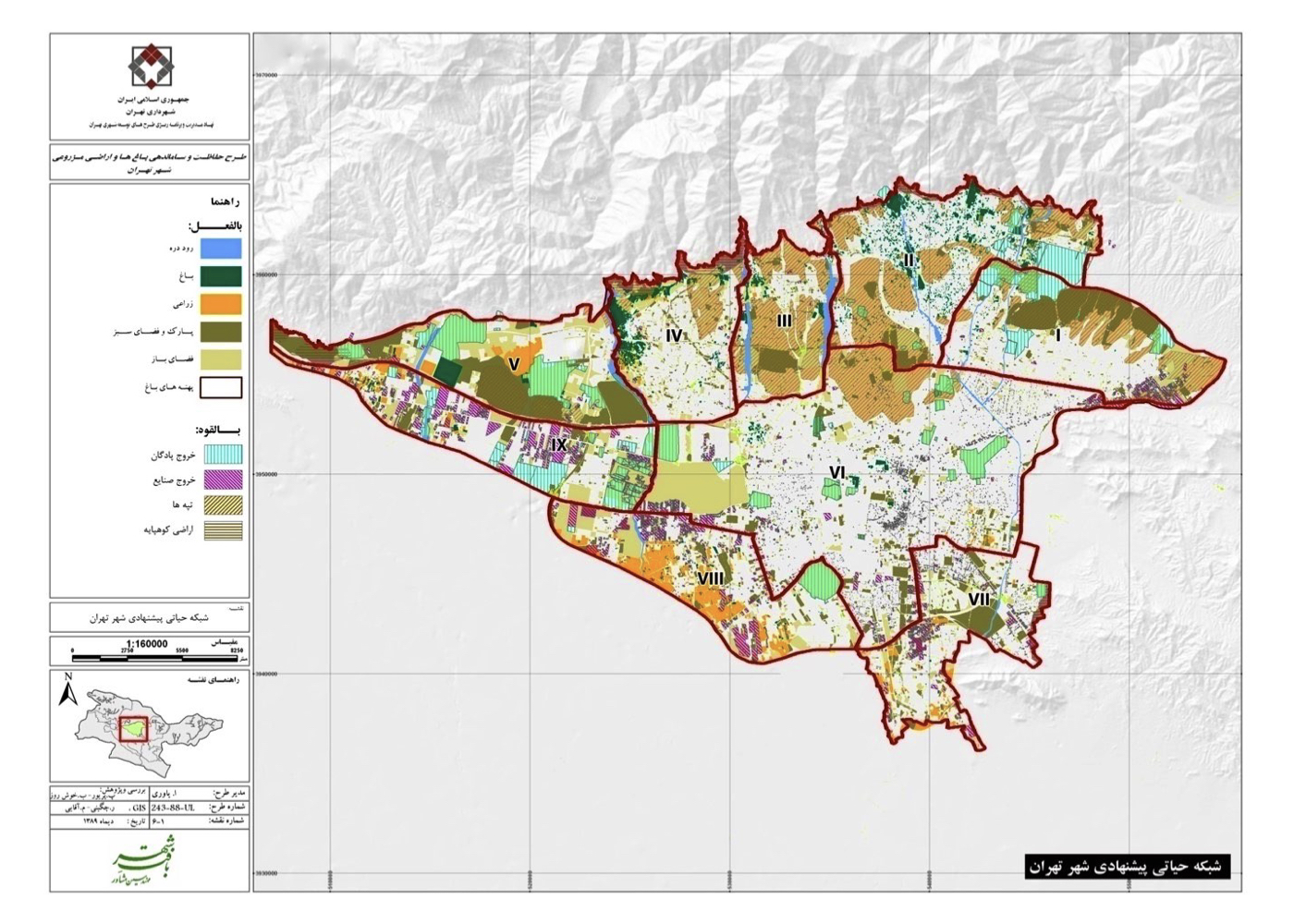

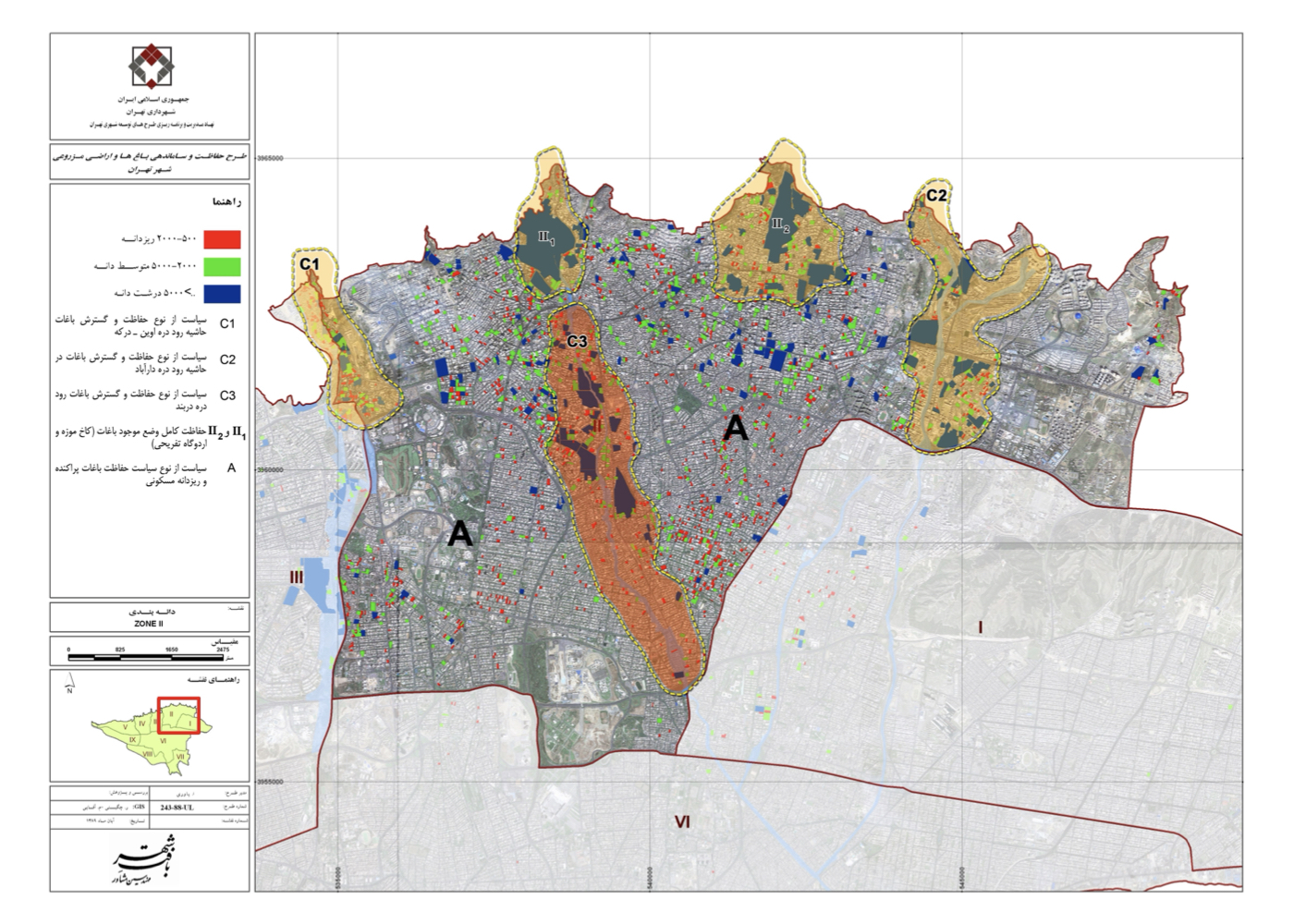

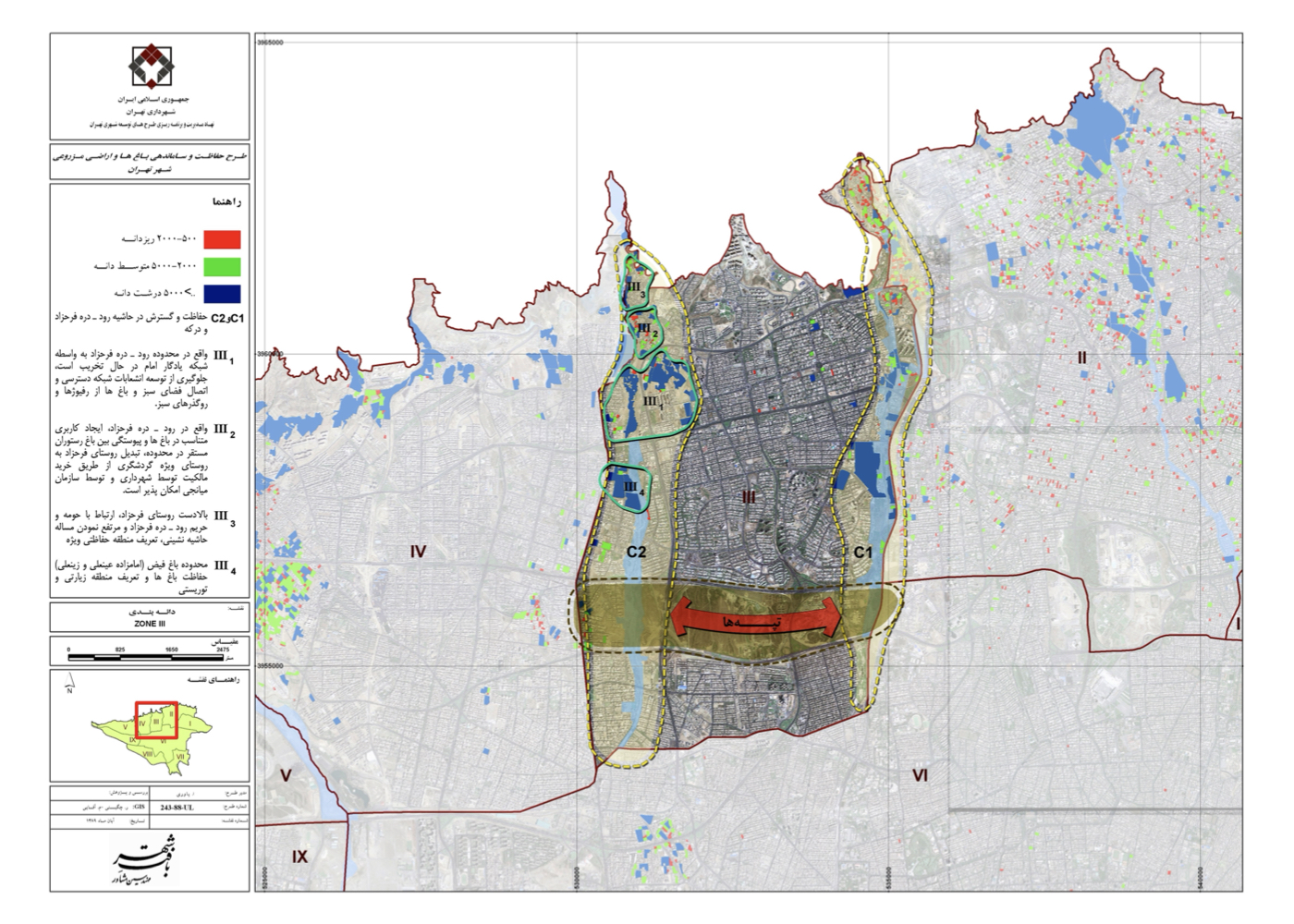

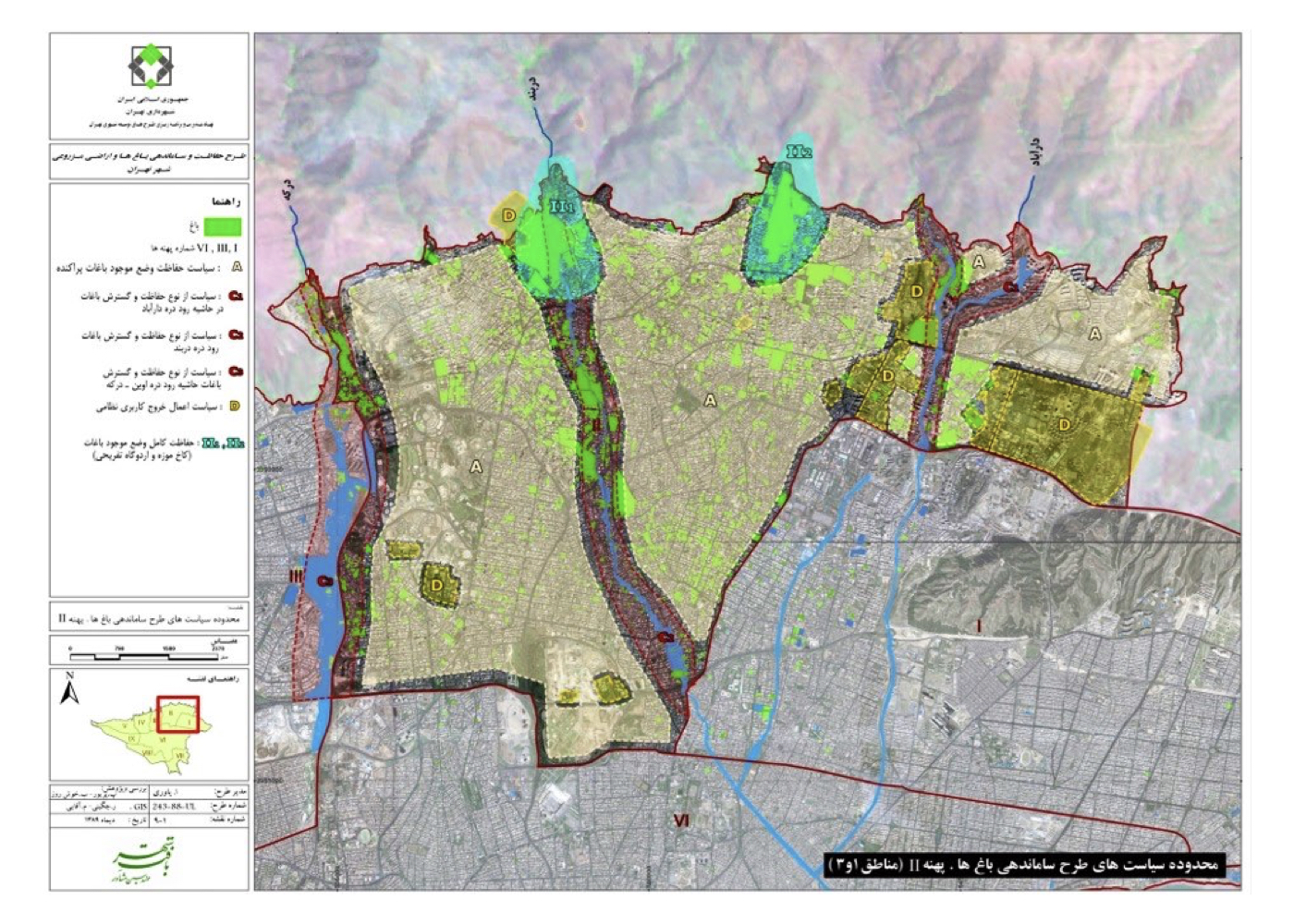

1. Dividing the 700 km² area of Tehran into 9 ecological zones

2. Defining sub-zones and special areas within each ecological zone

3. Providing zone-specific strategies for protection, improvement, and adaptive planning

Project Continuation Status:

The strategic phase of the plan was completed and approved, but its progression was halted due to a change in municipal leadership.

Additional Note:

One of the project’s lead experts, a faculty member at Tarbiat Modares University, later continued the project independently through a university contract — with the hope that it will yield beneficial results.

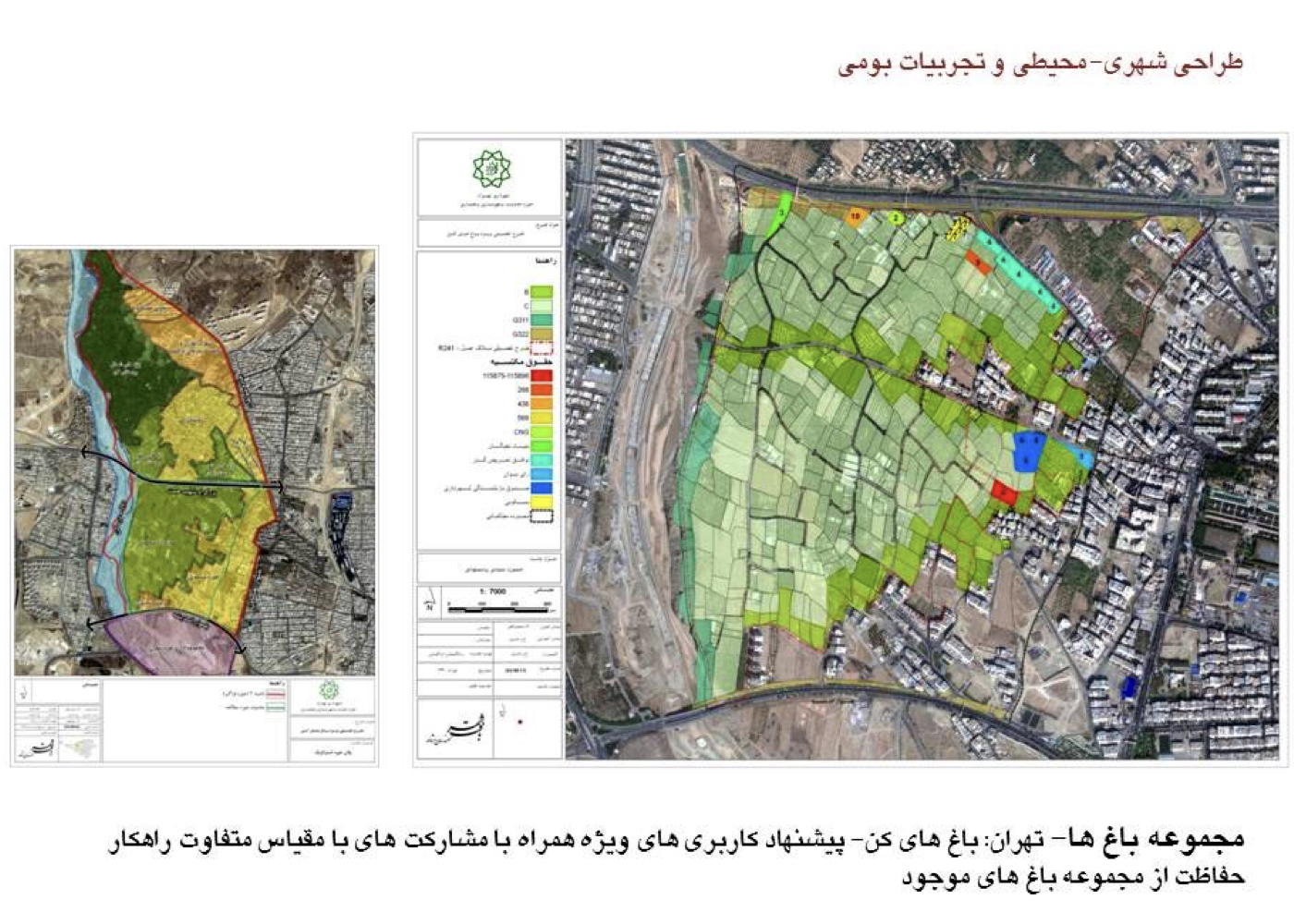

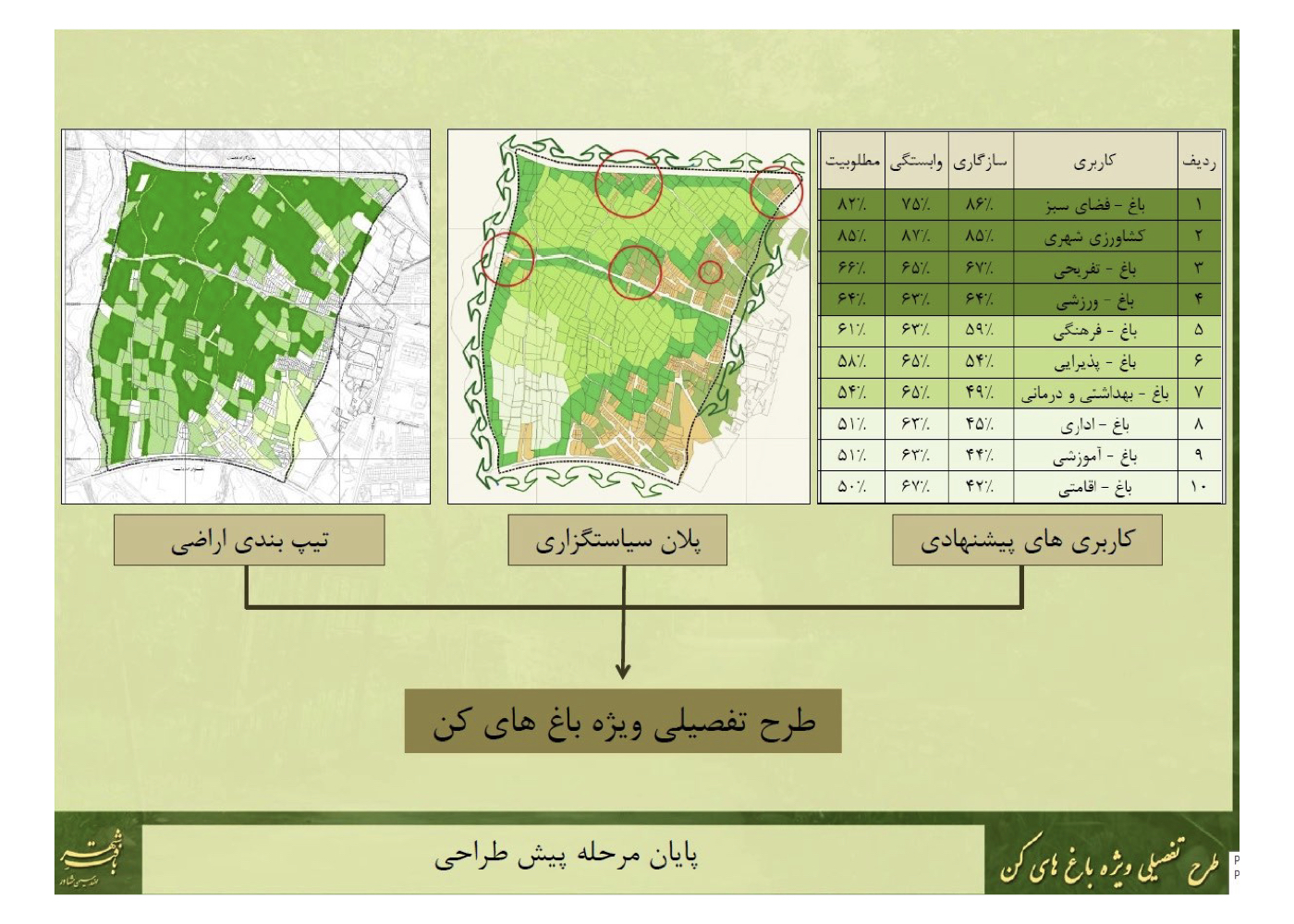

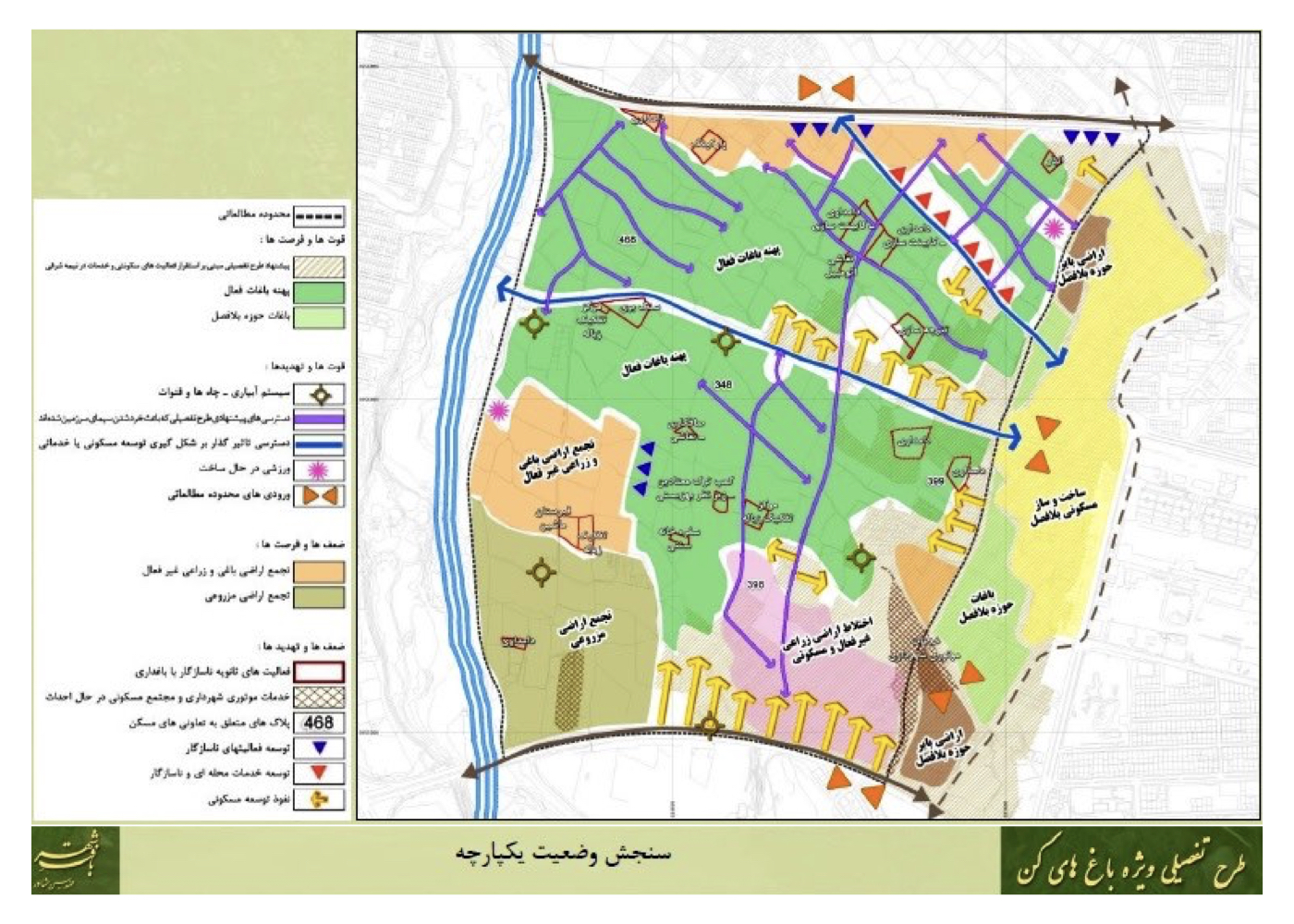

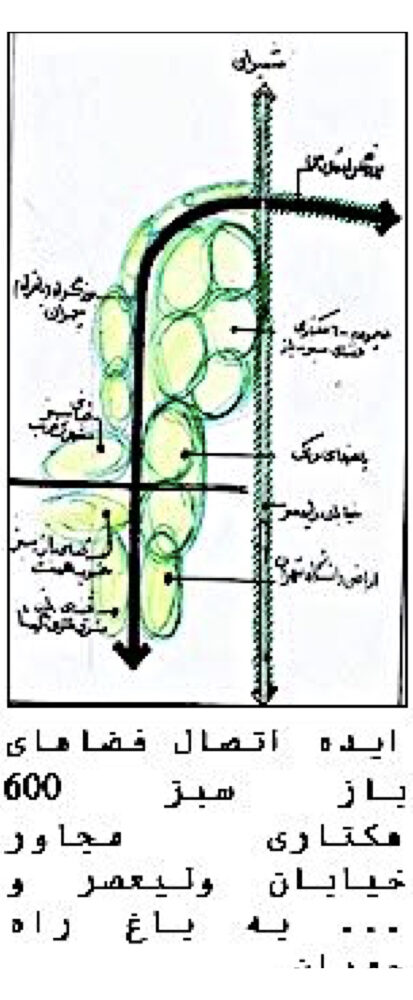

Special Plan for the Kan Gardens (Strategic)

Summary of Proposal:

Strategic protection and revitalization of the Kan Gardens, guided by environmental analysis and ecological landscape planning.

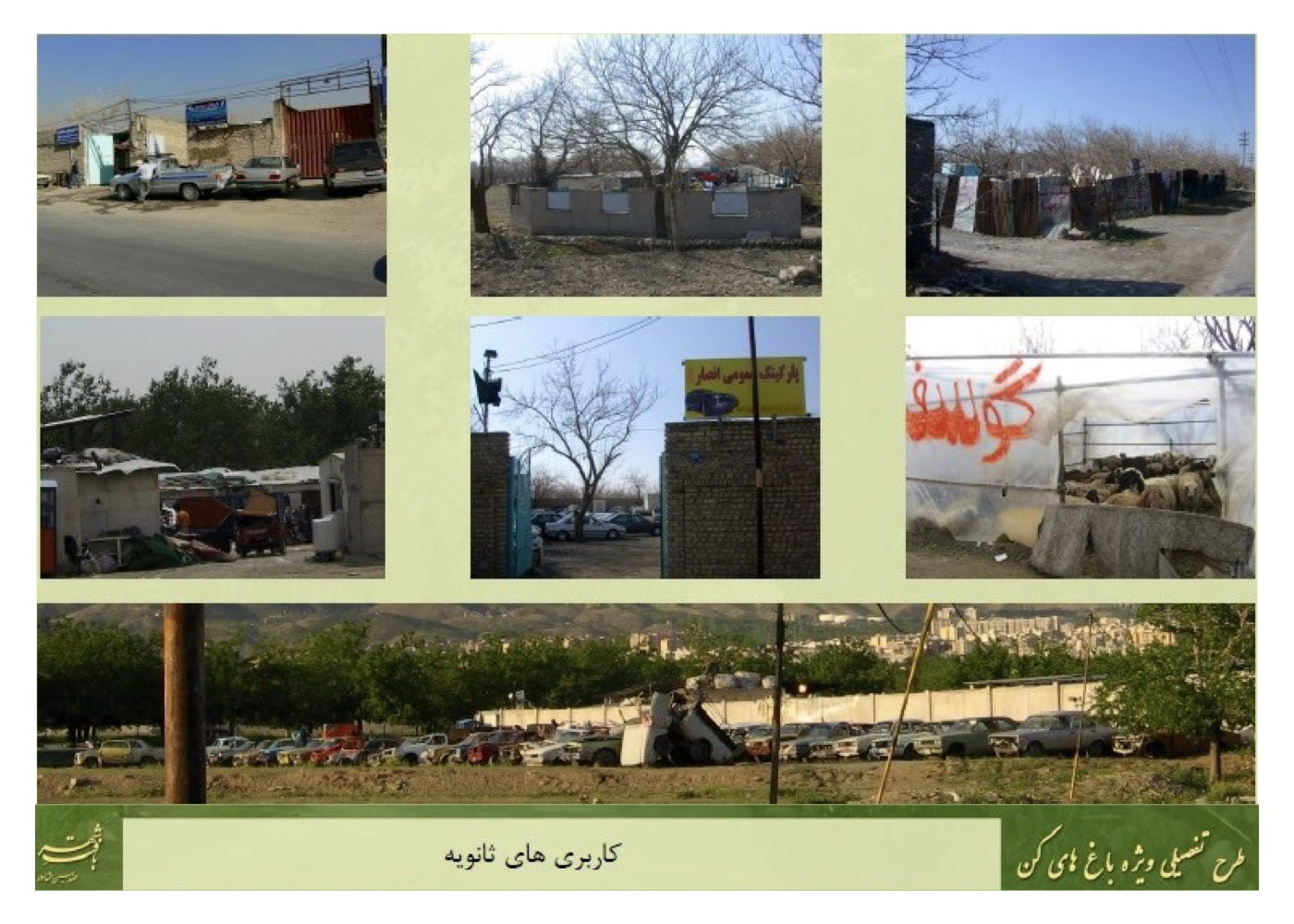

The total area of the northern, central, and southern segments exceeds 600 hectares. Hemmat Expressway was routed through the middle of the gardens, resulting in severe damage, disruption of irrigation systems, and accelerating land use changes. Further pressures from new urban roads and municipal land acquisition deals have worsened the destruction.

Study Area:

The study focused on the southern section, approximately 200 hectares in size.

Study Areas Covered:

Threats, limitations, opportunities, and capacities — with a special emphasis on green space preservation

Summary of Strategies and Interventions:

1. Creating a landscape matrix to reconnect the northern and southern garden zones

2. Reorganizing the Hemmat Highway edge to minimize ecological fragmentation

3. Enhancing the interface with the Kan River to restore water dynamics and landscape continuity

4. Redirecting construction patterns in favor of riparian green space restoration

5. Establishing water collection basins to support upstream infiltration and replenish aquifers

6. Redesigning streets like Andisheh and Ta’avon to better align with ecological and urban structure

Key Priorities for Pre-Design Phase:

1. Secure and sustainable water supply

2. Access and connectivity

3. Parcel patterning and land ownership regulation

4. Ecological quality and vegetation density

5. Spatial coherence of garden areas

A priority matrix was prepared at the end of the pre-design phase to guide future implementation.

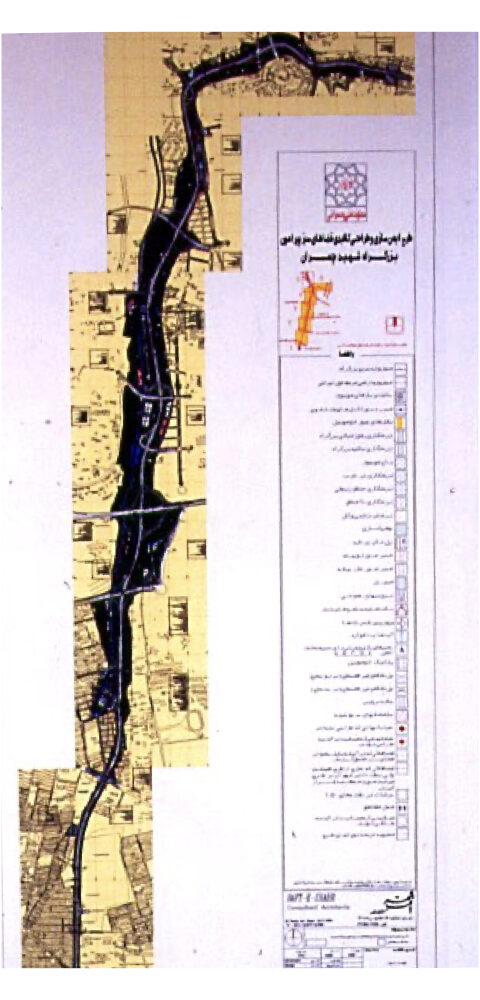

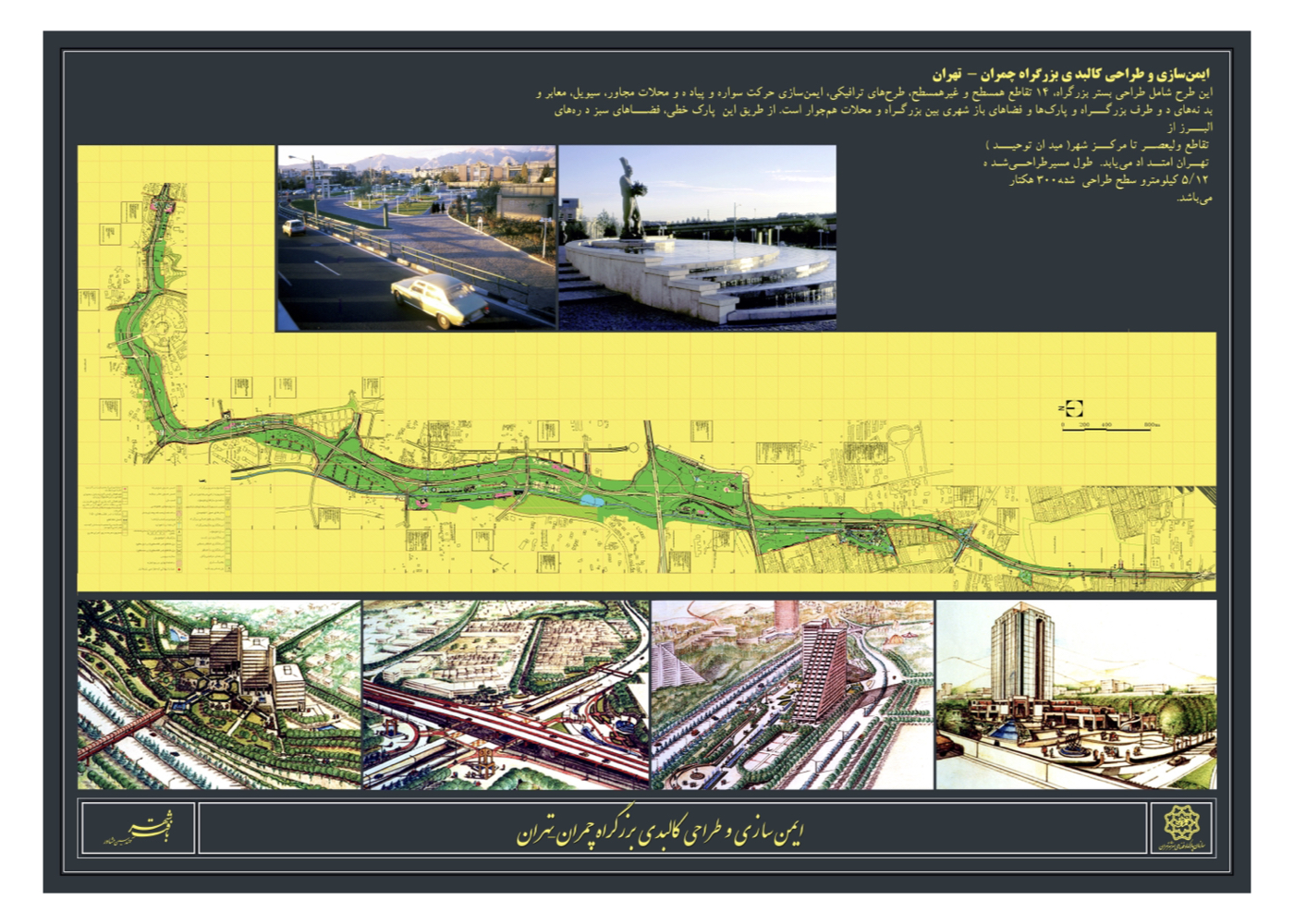

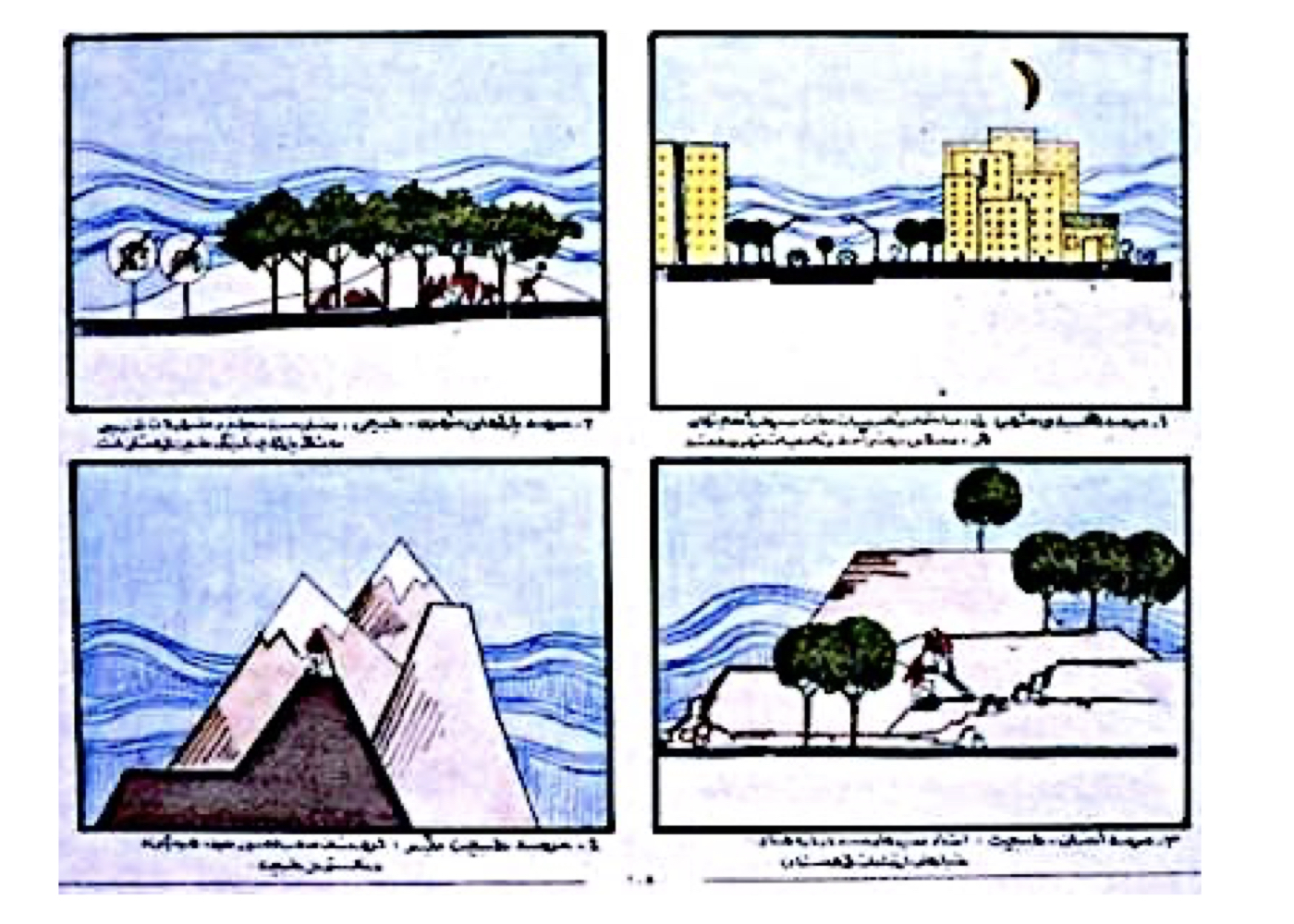

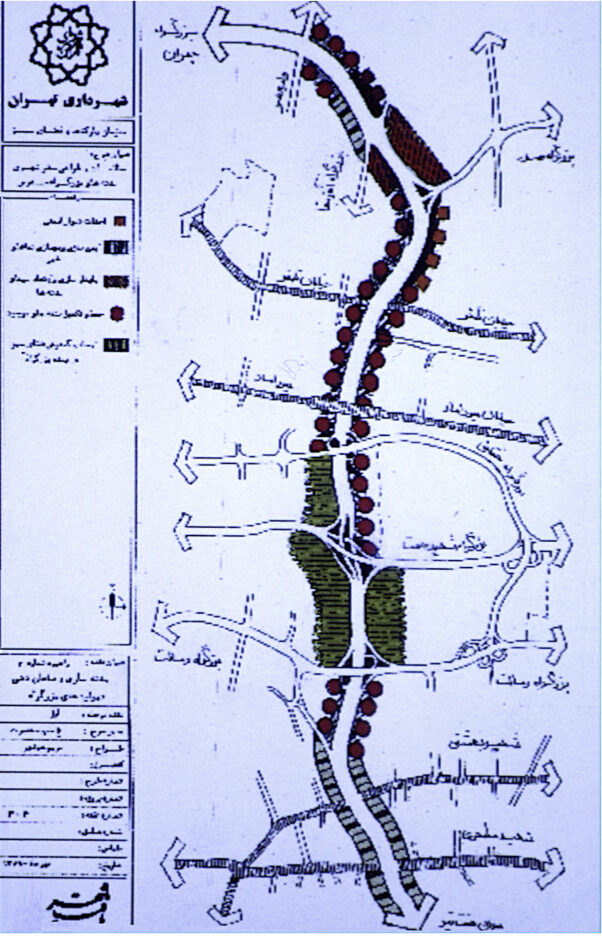

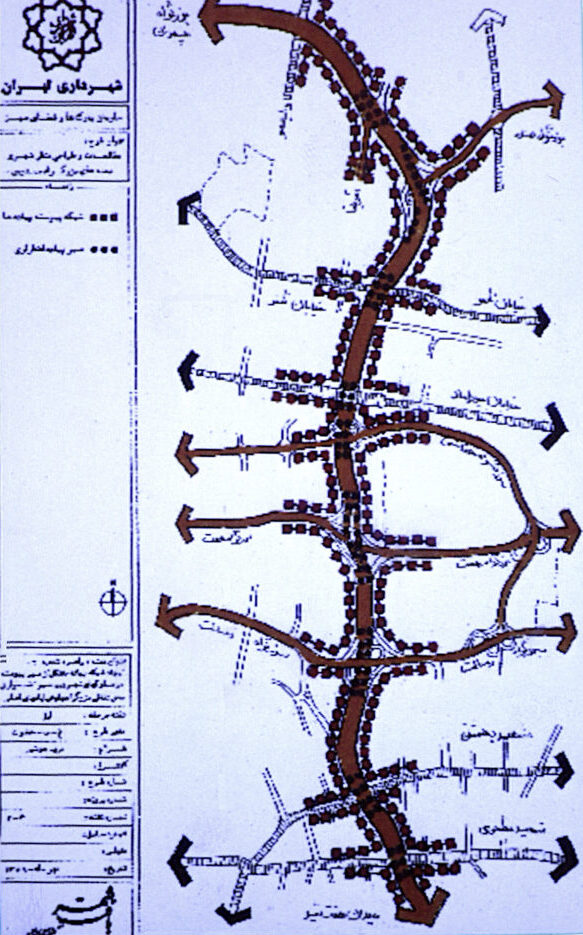

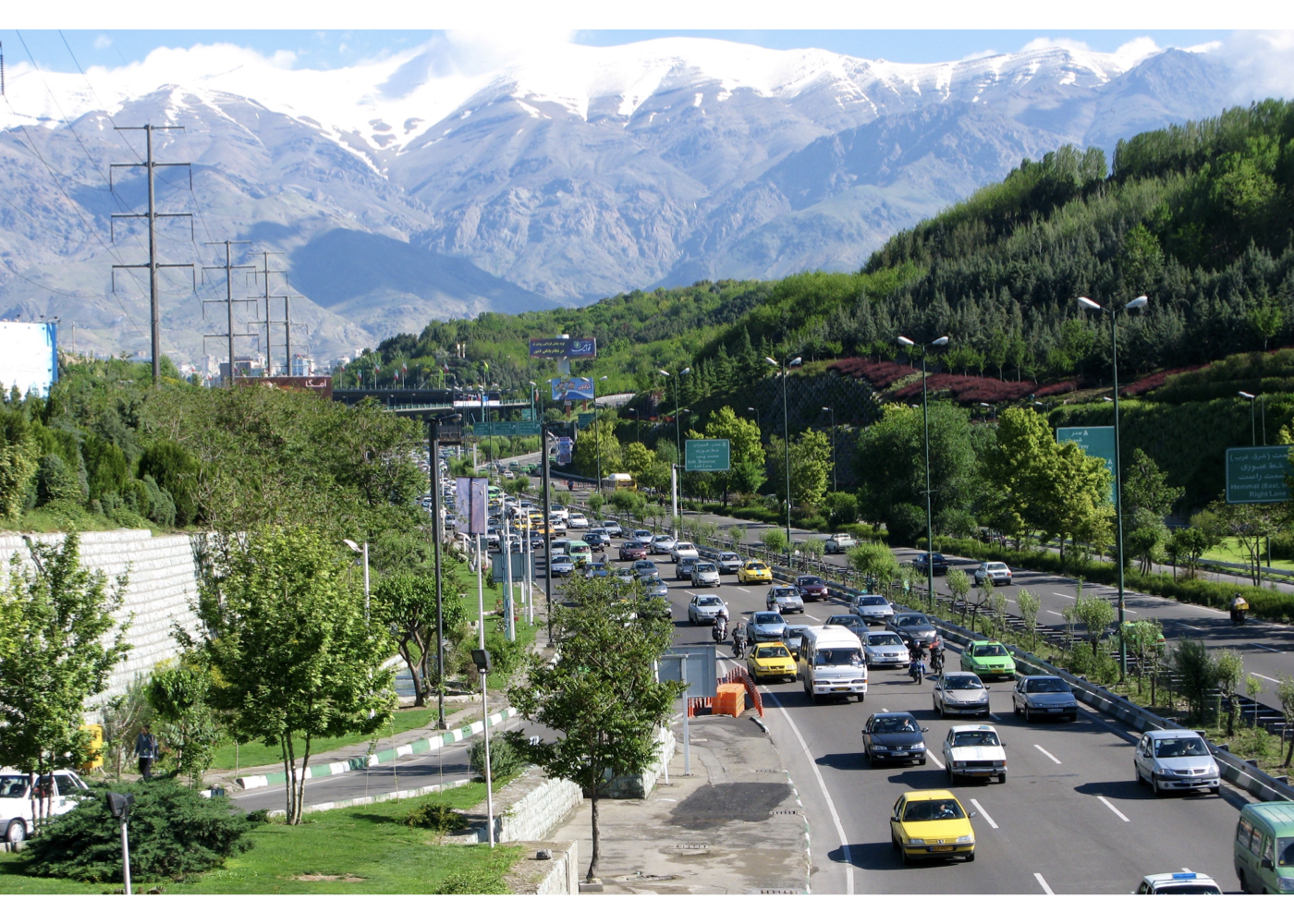

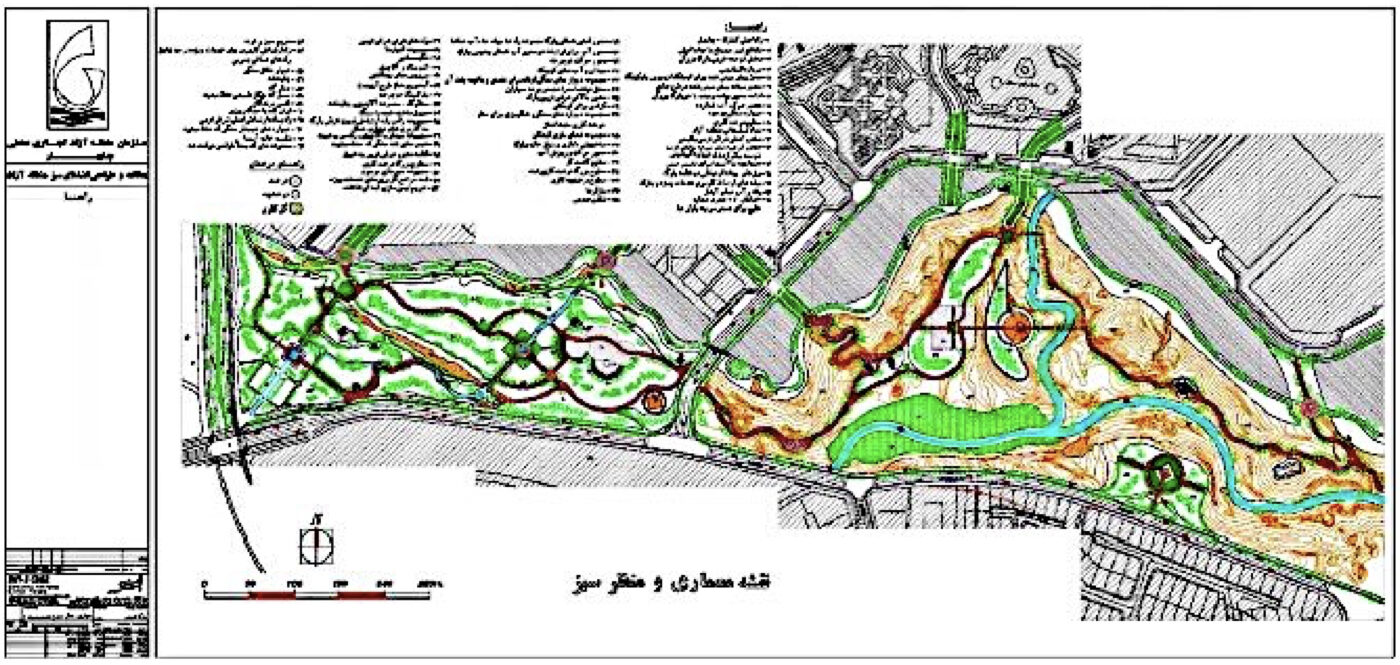

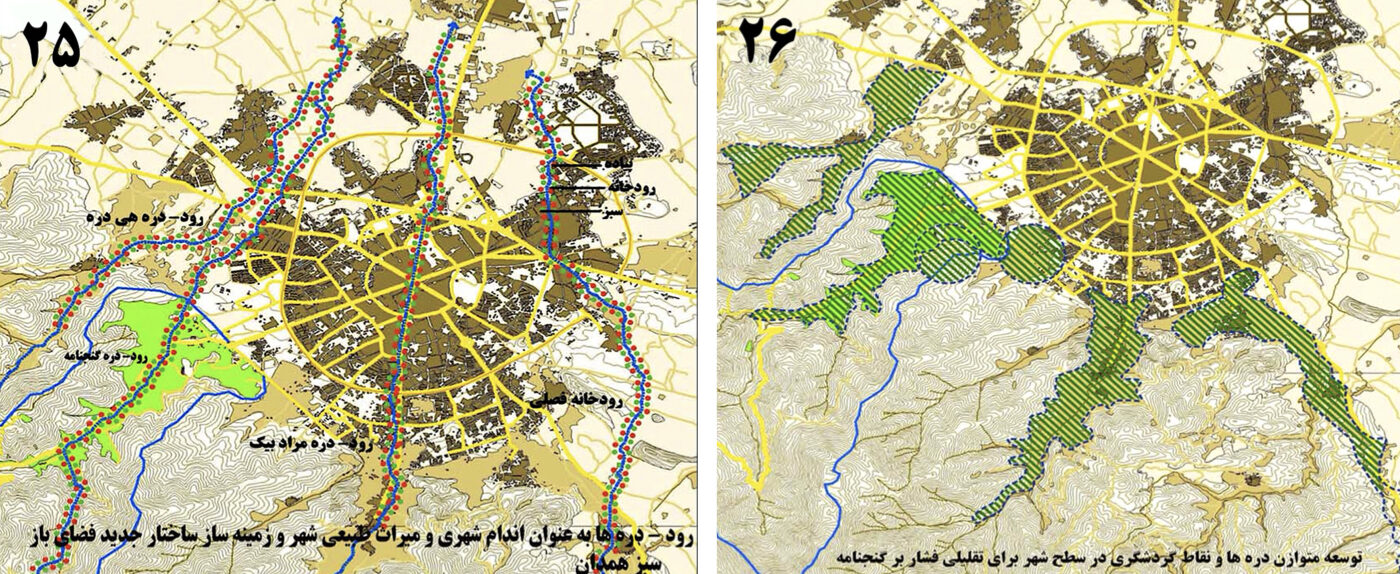

Physical and Environmental Design of the Chamran Highway Corridor (Strategic – Phases I & II)

Summary of Proposal:

Reviving the greenway spirit and extending the lush landscape of northern Tehran into the urban fabric of southern districts

Background:

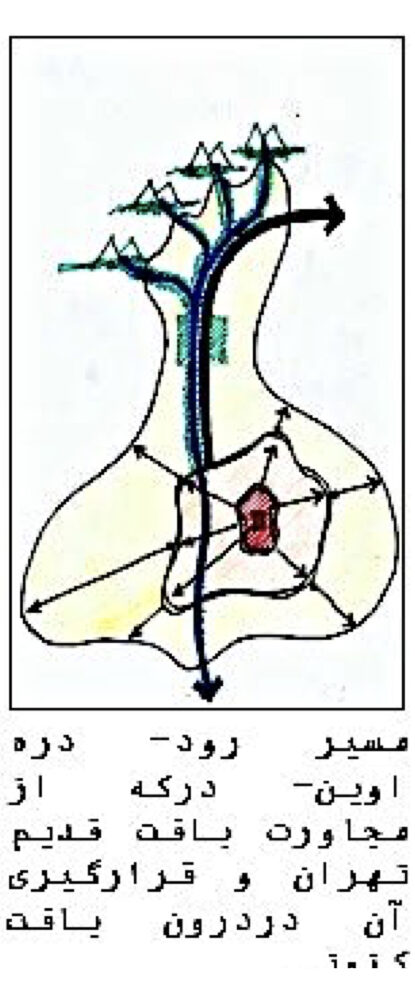

Chamran Highway was constructed in the 1960s as a major north–south axis in Tehran. It was originally called “Parkway” due to its path through Vanak Gardens and the Ovin–Darakeh orchards to the north. A regulation was established requiring a 35-meter buffer zone on both sides of the highway, yet implementation faced challenges, especially from nearby garden owners and residents. Aerial surveys were conducted via helicopter alongside detailed field assessments. Chamran Highway spans 12.5 km across several municipal districts. Due to differing perspectives among city officials, the corridor was divided into five zones, each overseen by an executive manager.

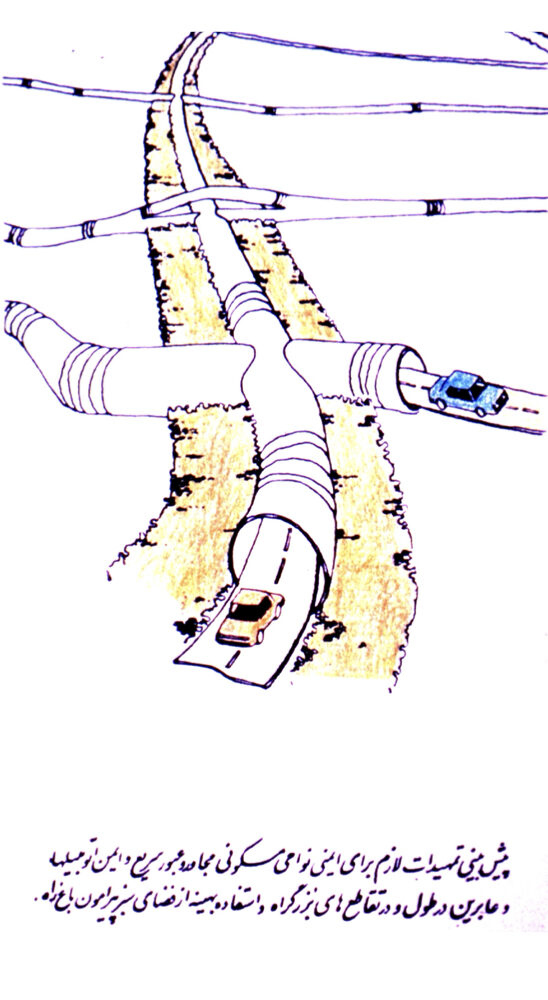

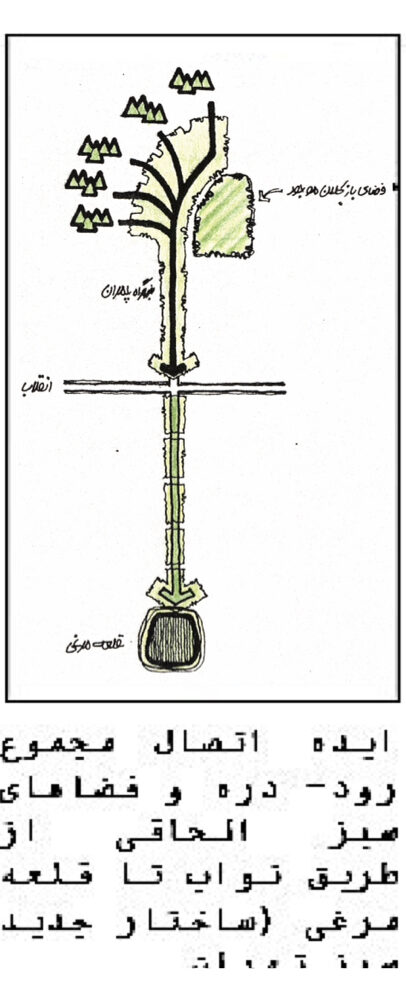

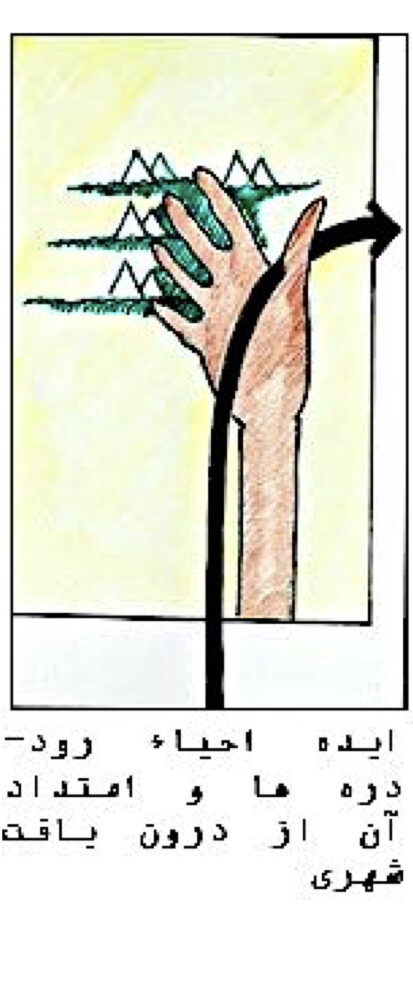

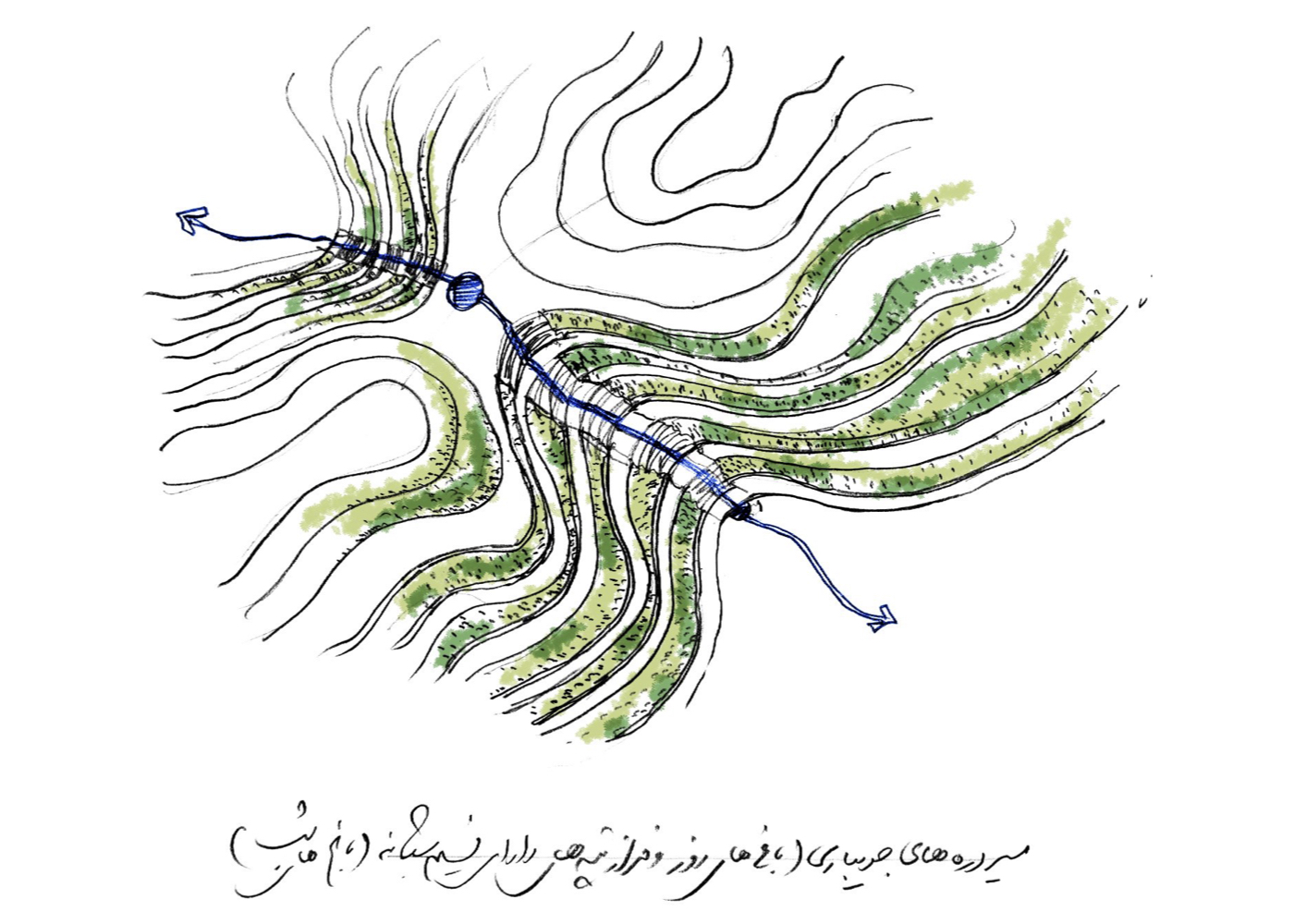

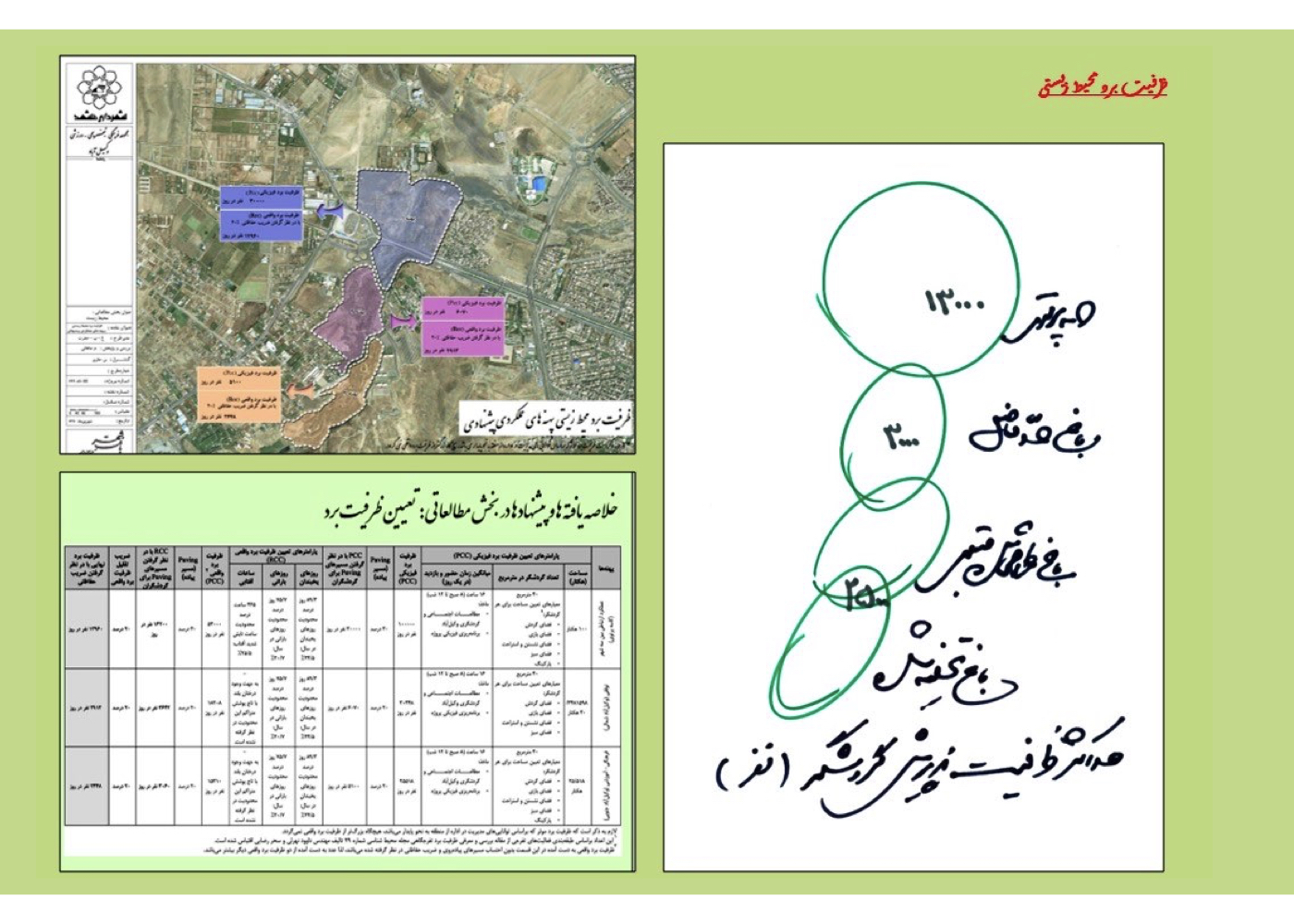

The “Green Palm of Tehran” Concept:

In the attached sketch, mountain ridges are depicted as fingers, and river–valleys as the spaces between — forming the metaphorical “green palm” of Tehran.

Summary of Key Ideas and Strategies:

1. The highway was once at the city’s edge but now lies at its center.

2. It runs parallel to the Ovin–Darakeh river-valley, both influencing and being influenced by this natural corridor.

3. Proximity to historic gardens and the river grants it ecological and cultural significance.

4. At its junction with Valiasr Street (formerly Pahlavi), it interfaces with institutional gardens, hospitals, and exhibition grounds totaling around 600 hectares.

5. Linking these sites can create a continuous green corridor from Vanak Gardens to Towhid Square.

6. Continuing to Ghal’e Morghi (200 hectares), the area could host an urban green campus.

7. This green axis, from the Alborz foothills to Tehran’s southern edge, would form an ecological backbone for the city.

Another Core Idea of the Plan:

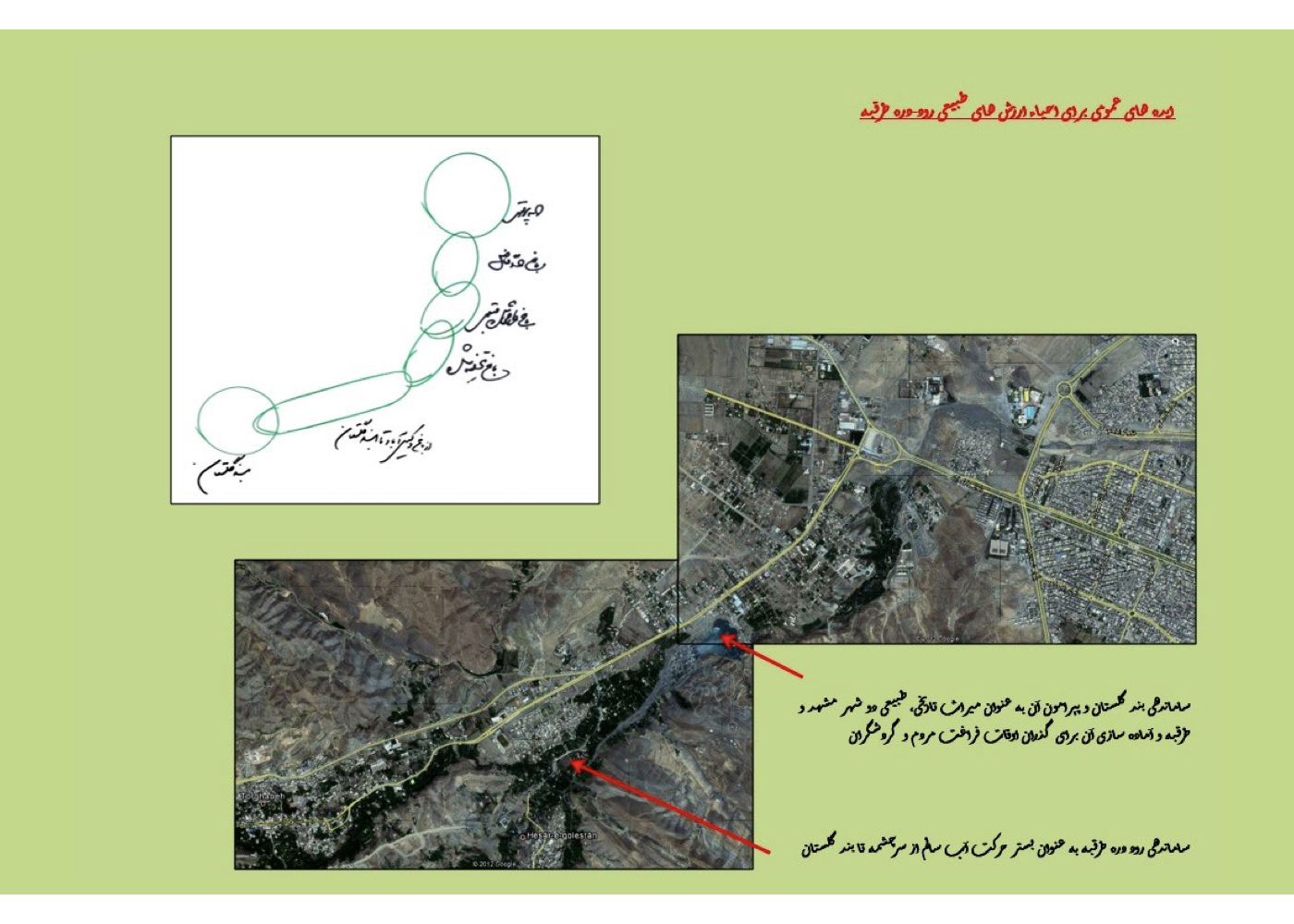

A paradigm shift in naming and managing Tehran’s seasonal waterways — from “canal” (masil) to “river–valley” (rud–darreh)

Benefits of This Conceptual Shift:

1. Recognizing river–valleys as critical ecological assets

2. Reviving them as green ecological corridors from the mountains into urban neighborhoods

3. Purging pollutants and physically integrating valleys into city life

River–Valleys Considered for Ecological Integration:

Darabad, Golabdarreh, Ovin, Darakeh, Farahzad and Kan

Implementation Status:

1. Strategic and Phase I & II plans were approved.

2. Implementation deviated due to leadership change and new highway intersections and expo facilities.

3. Ghal’e Morghi was later turned into Velayat Park, but the Chamran–Navab green corridor concept was abandoned.

4. Hemmat and Hakim highways damaged the natural state of several valleys by crossing directly over them.

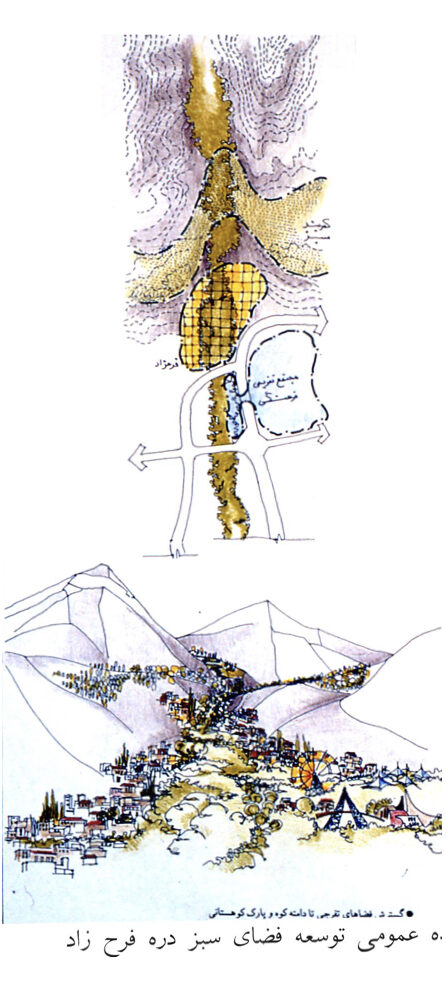

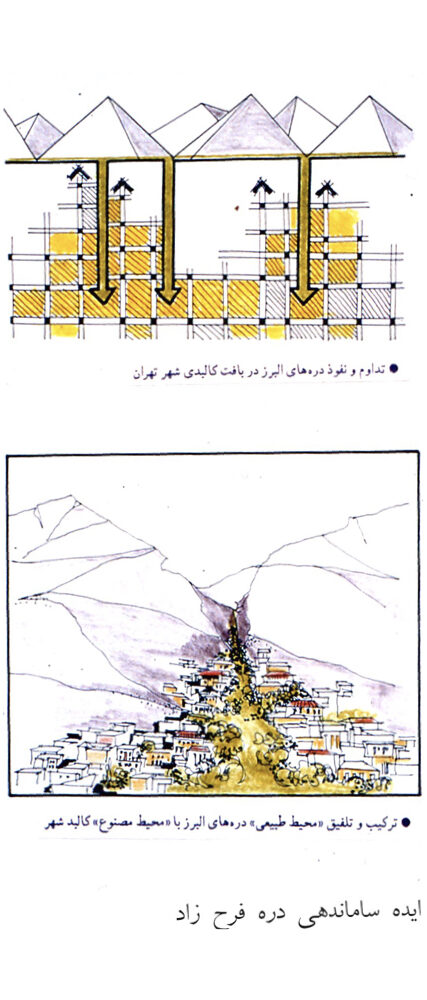

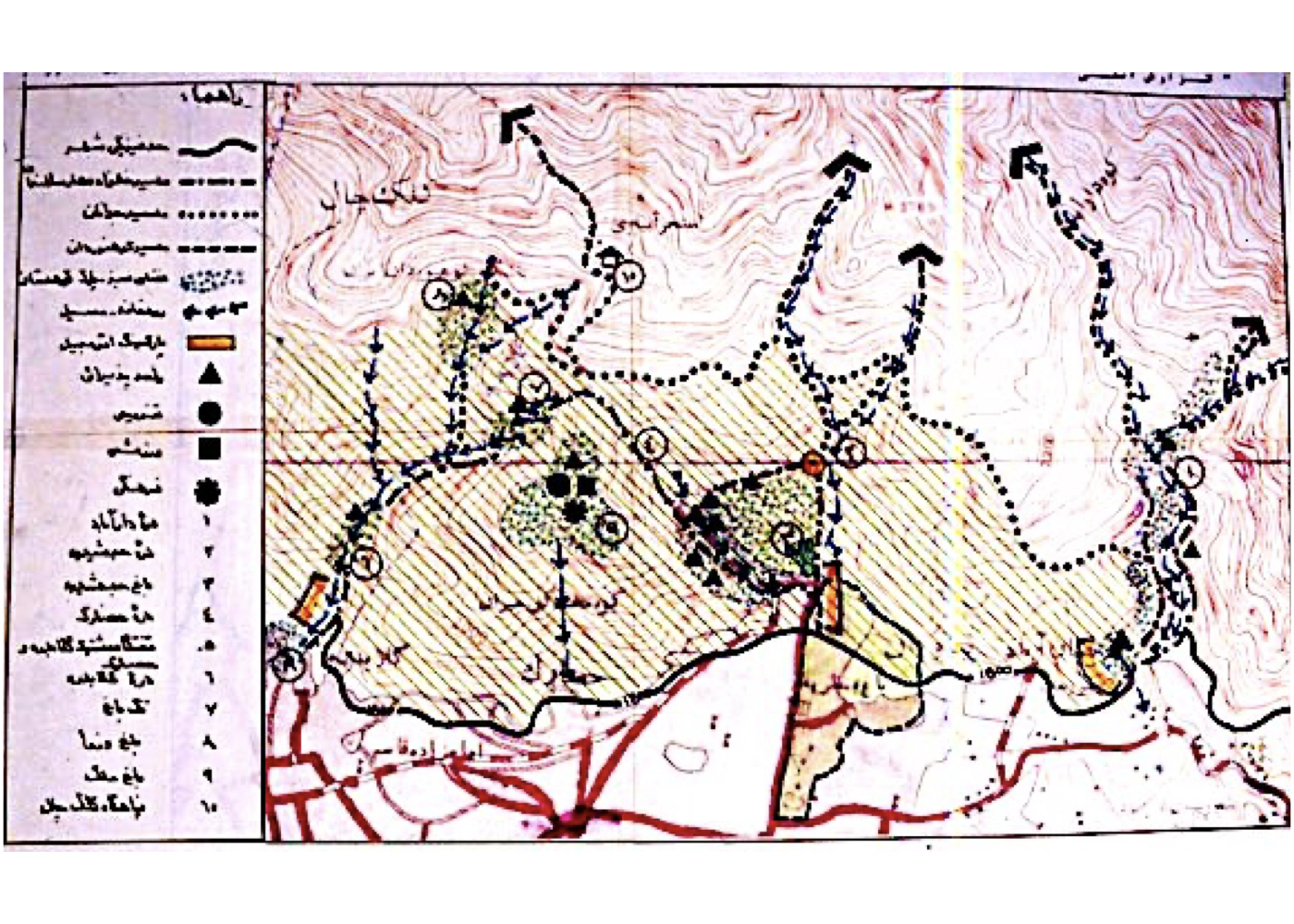

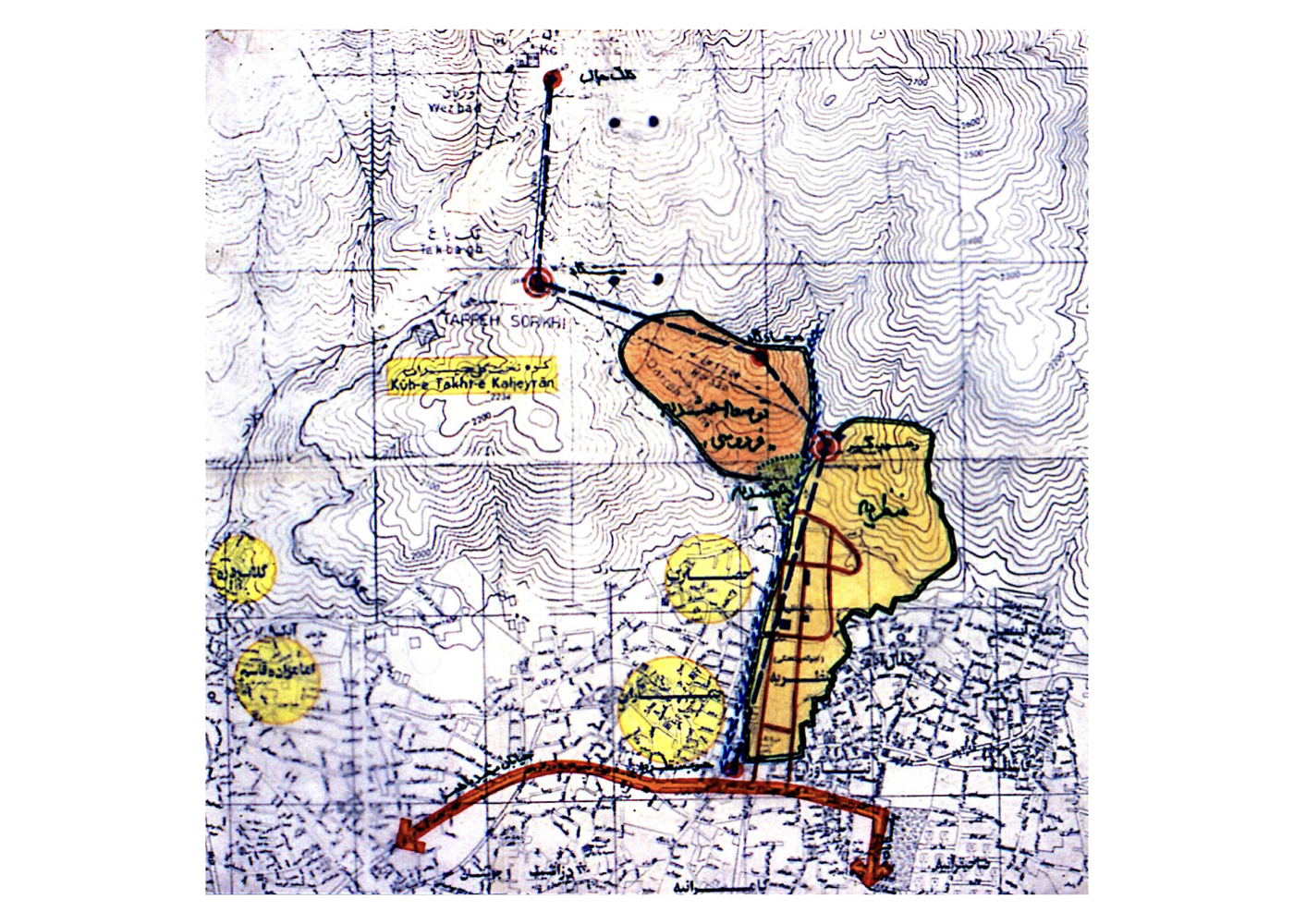

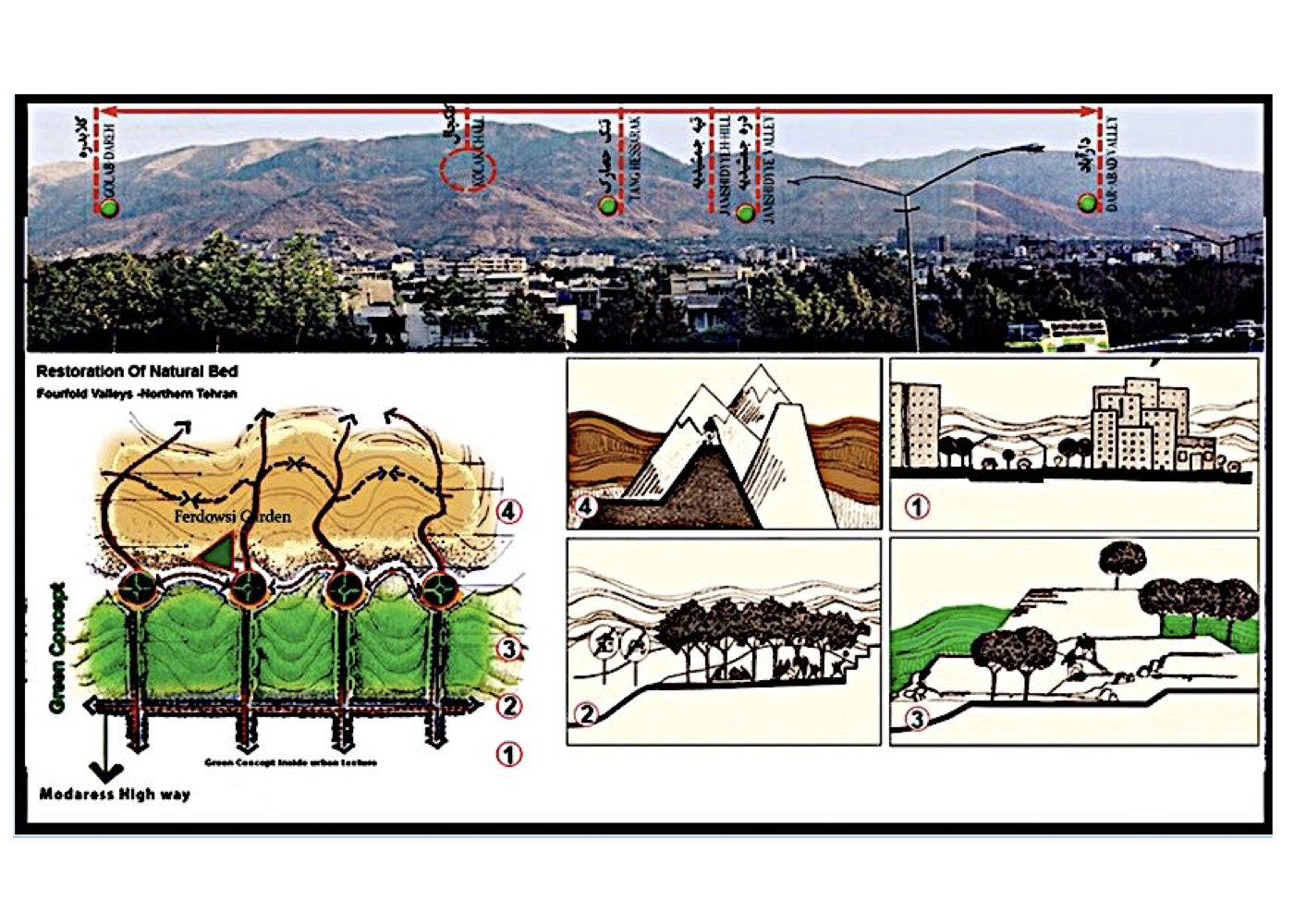

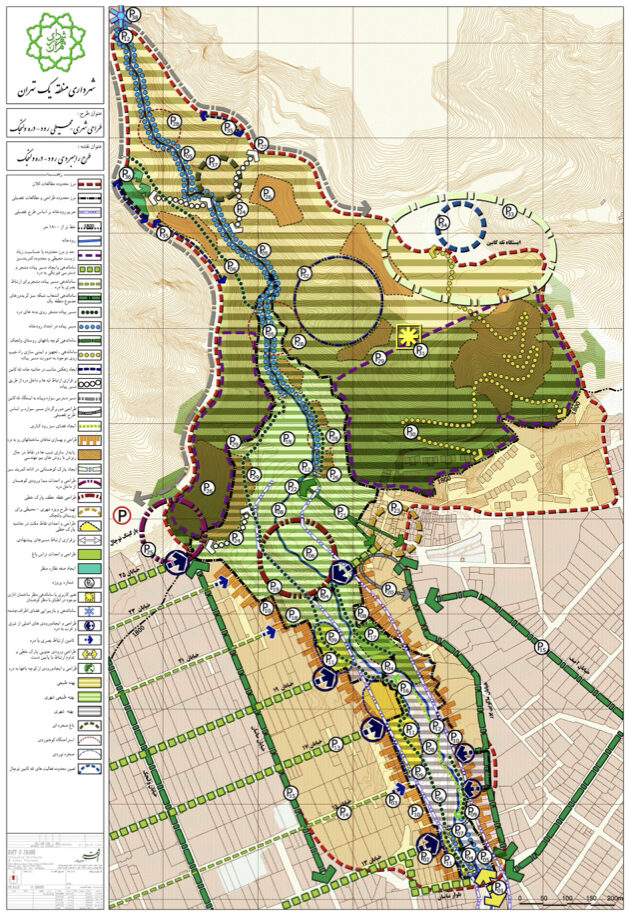

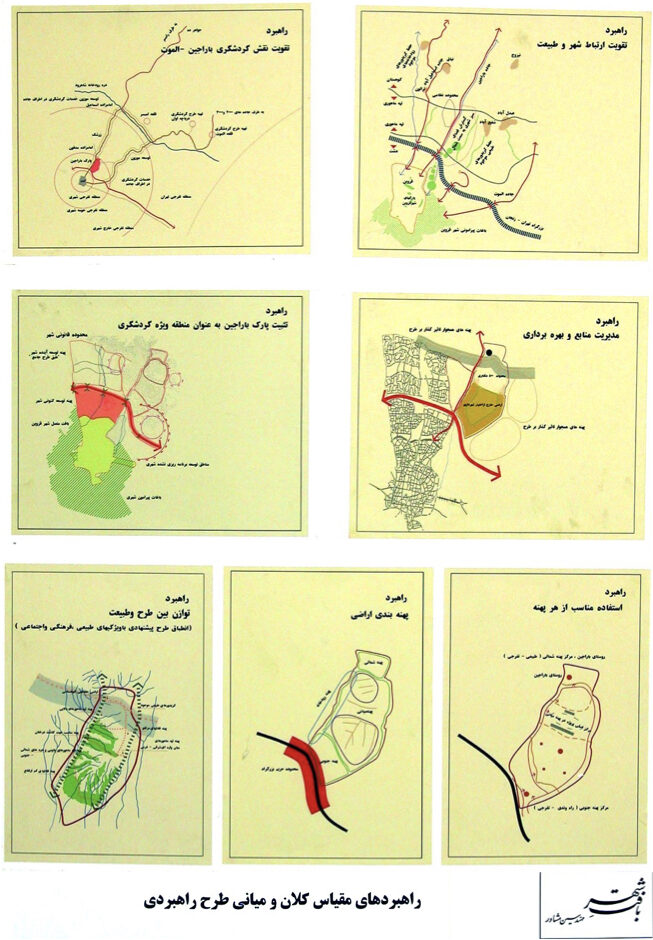

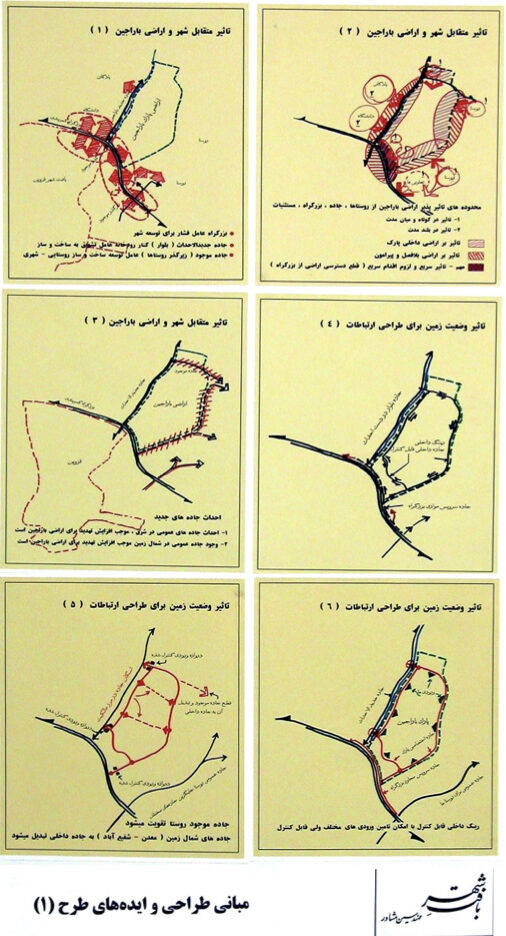

Urban – Environmental Design for the Kolakchal Valleys (Strategic)

Summary of Proposal:

Zoning the northern elevations of Tehran and providing protective strategies against rapid urban encroachment into the valleys.

Background:

In recent decades, explosive urban growth in Tehran and its neighboring cities has aggressively expanded into foothill areas, leading to the occupation of ridges, valleys, and lowland slopes, threatening these natural assets. During the design contract for Ferdowsi Garden, it was proposed to conduct a comprehensive environmental study of four valleys linked to Kalakchal.

The four valleys studied were:

Shahabad (Darabad), Jamshidieh, Tang-e-Hesarak and Golabdarreh – Together covering an area of approximately 12 km².

Main Objectives:

1. Establish a mountain design framework

2. Provide strategies to improve safety and environmental quality in Tehran’s northern highlands

Summary of Kalakchal Valley Environmental Design Strategies:

1. Zoning the mountainous and foothill areas into four zones:

A. Urban fabric

B. Mountain greenbelt

C. Active conservation

D. Pristine nature

2. Preventing urban expansion toward the mountains via designated buffer trails

3. Establishing a protective greenbelt in Zone 2

4. Valley Protection Strategies:

A. Repeal the law permitting construction up to 1800m elevation

B. Draft new legislation to stabilize the city’s northern boundary based on ecological criteria

C. Establish public gardens at valley entrances to prevent urban encroachment (e.g., Ferdowsi Garden as a prototype)

Implementation Status:

Ferdowsi Garden was studied and opened in 1996 as the first implemented phase of this strategic environmental initiative.