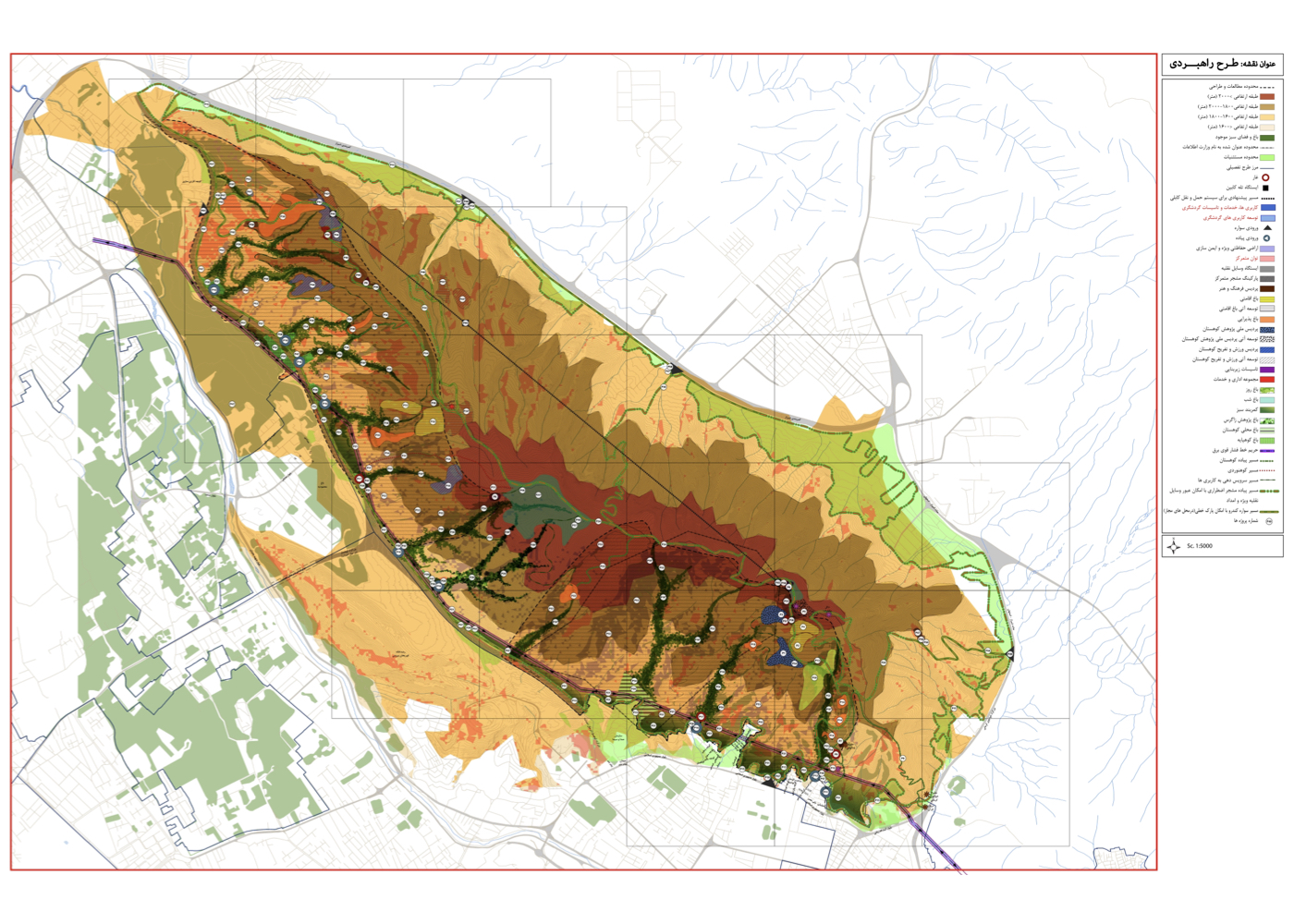

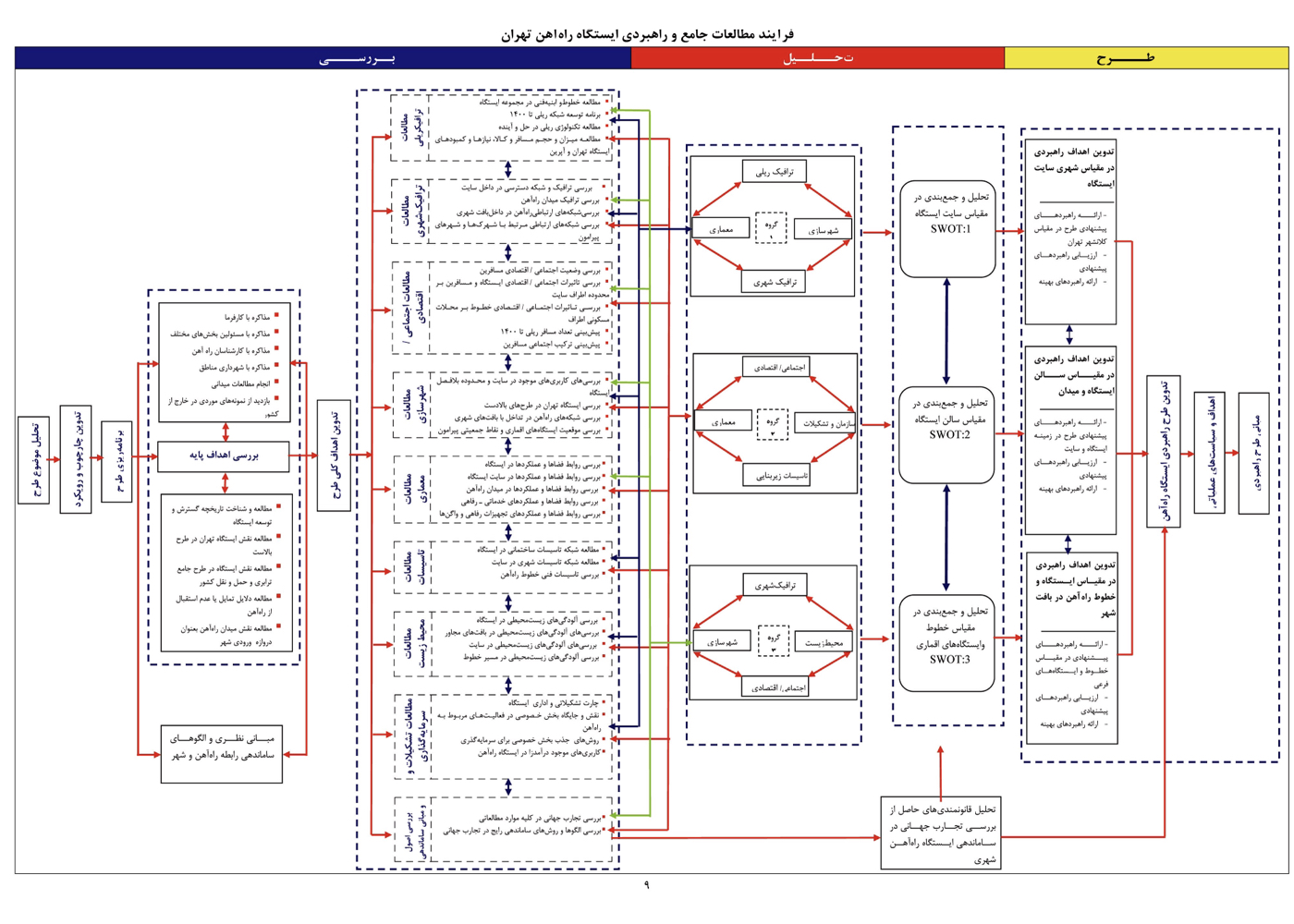

Urban-Environmental Design for Sustainable Urban Development

(Safeguarding, Revitalization and Responsibly Utilizing the Natural Assets of the City)

Preface:

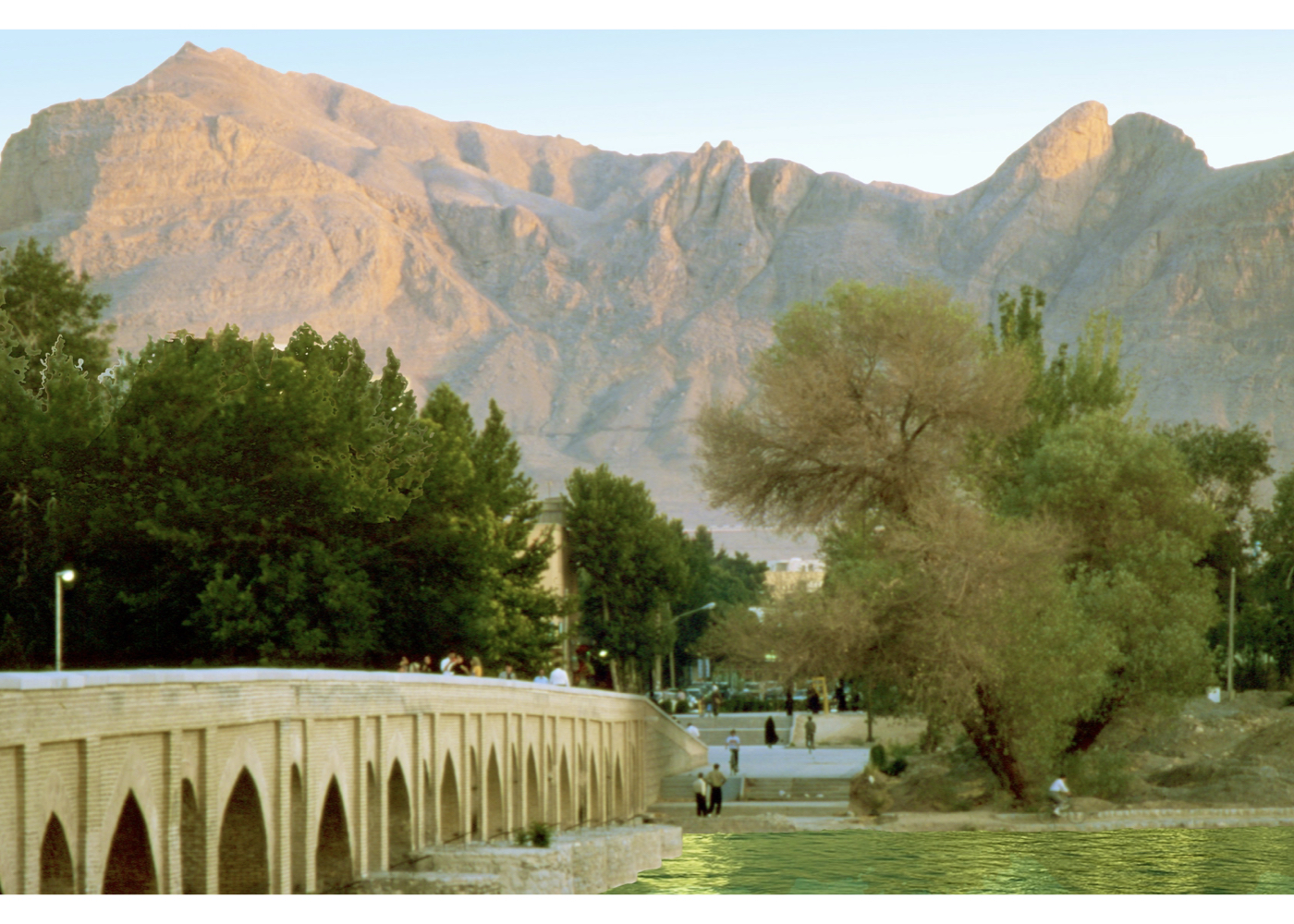

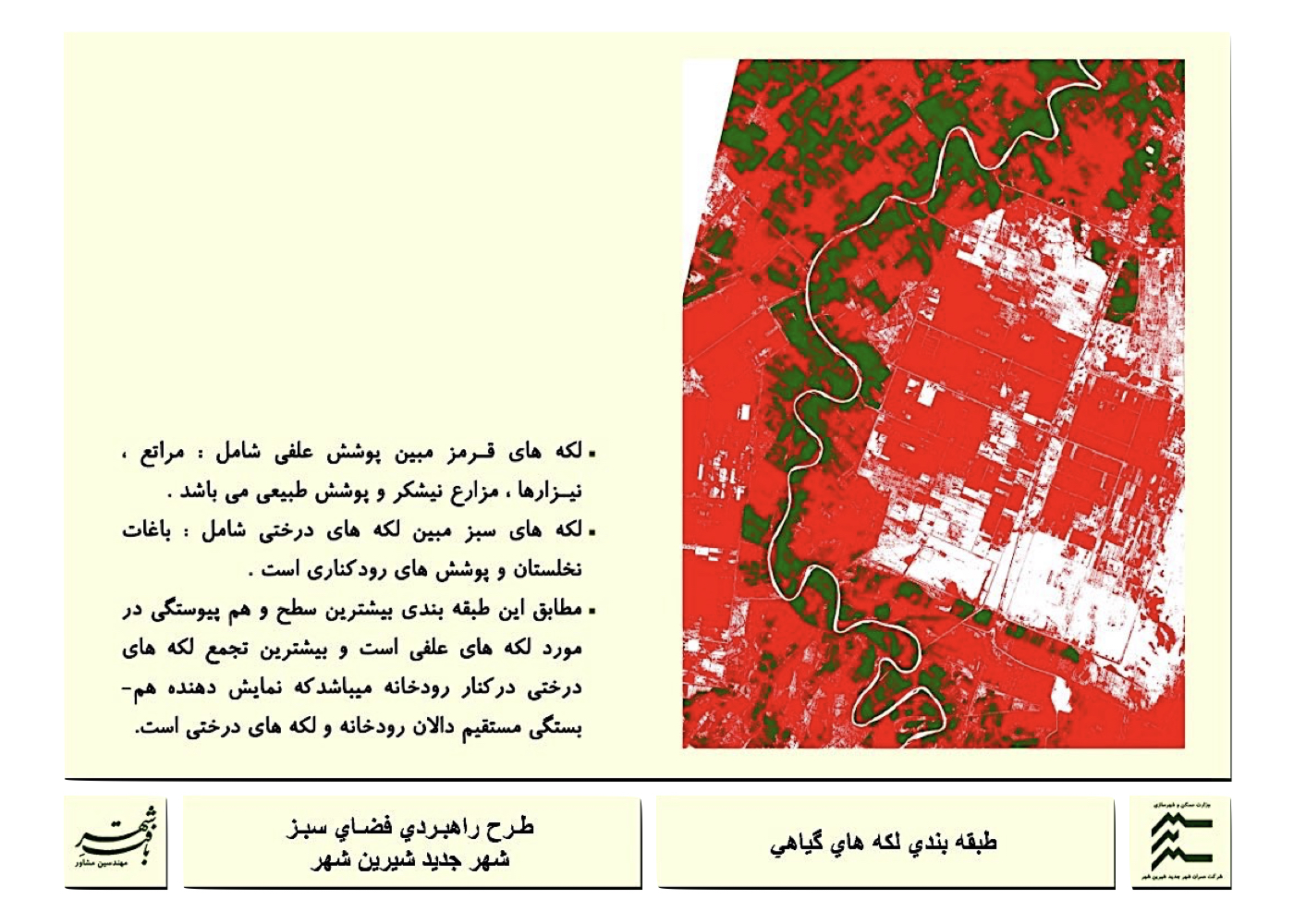

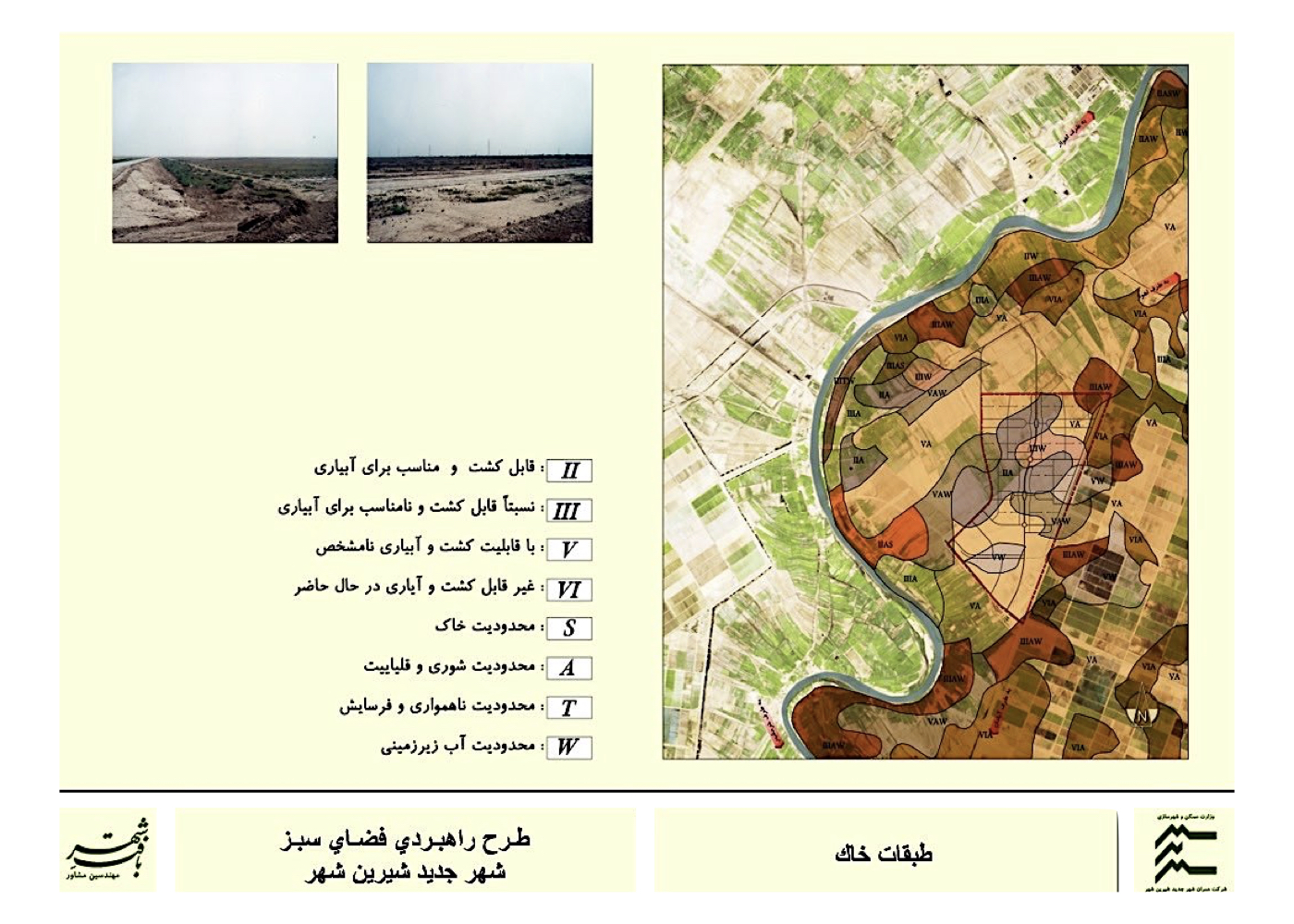

Our country lies in an arid, low-rainfall region with a vast desert at its center. The survival of many of our cities depends on one or more natural treasures, in mutual interaction with them.

Our wise ancestors, with deep knowledge of effective systems, structured the relationship between humans, cities, and the surrounding nature in an intelligent and forward-thinking manner—safeguarding natural assets while allowing for their use in line with ecological capacity, thus avoiding gradual degradation.

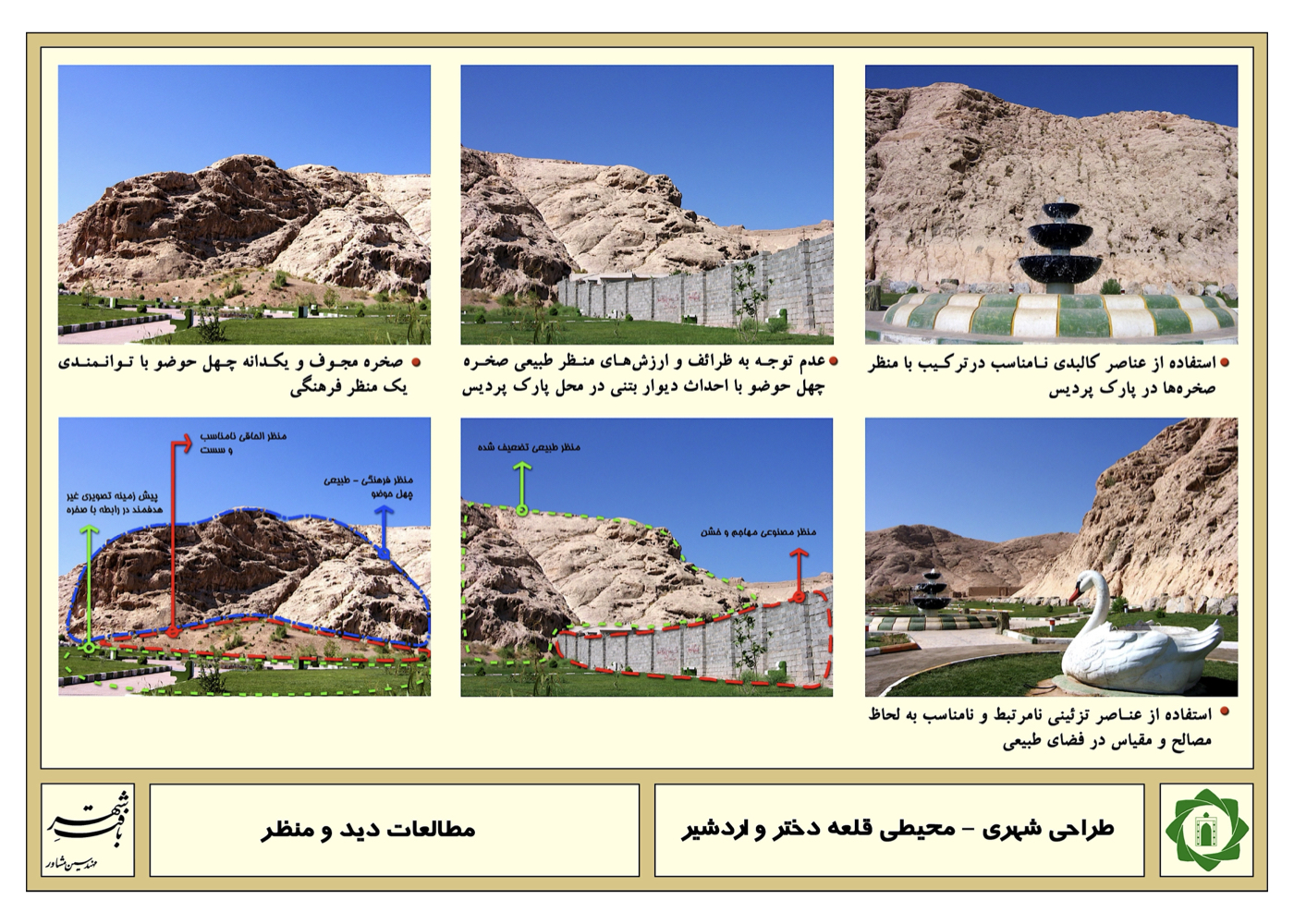

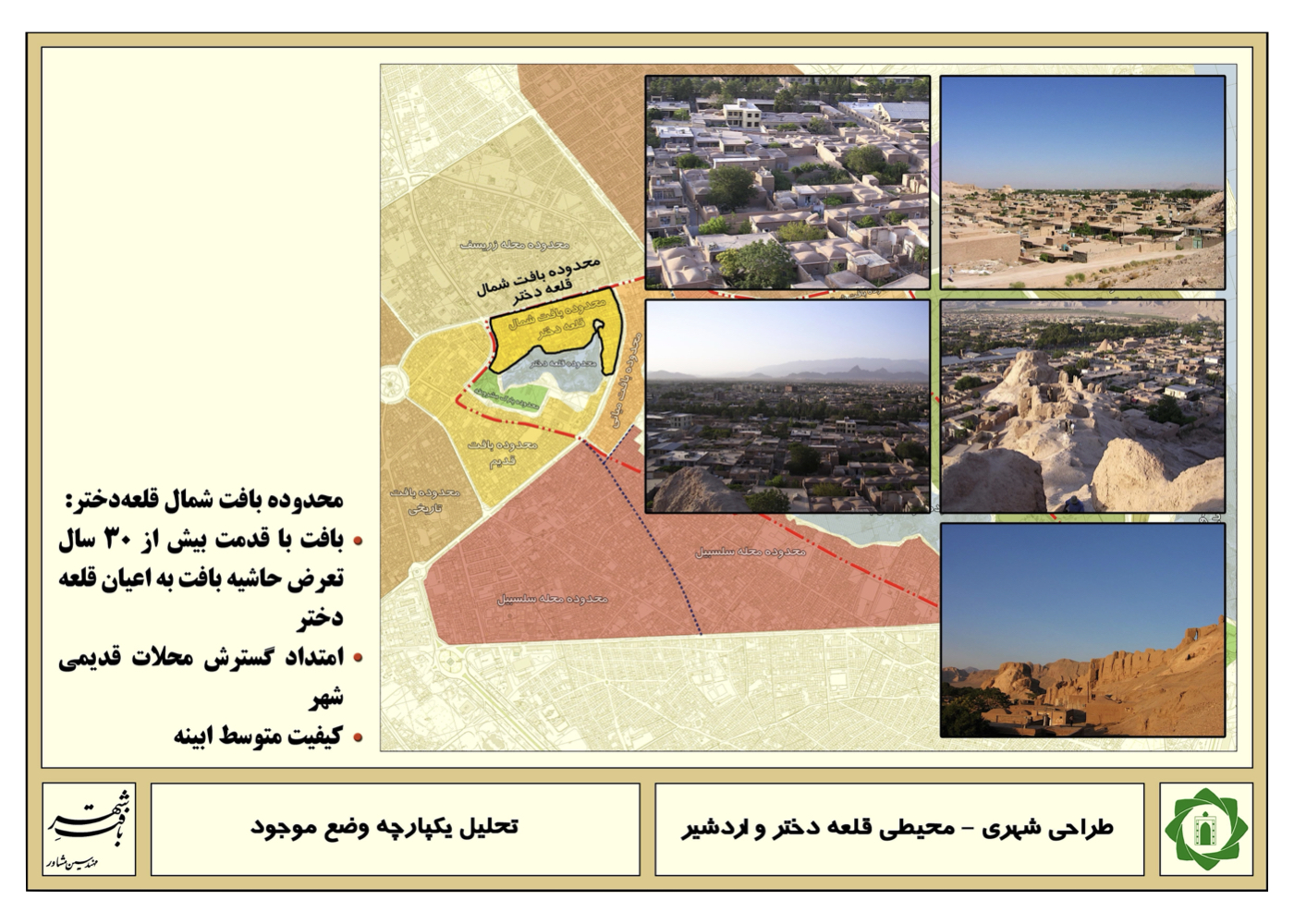

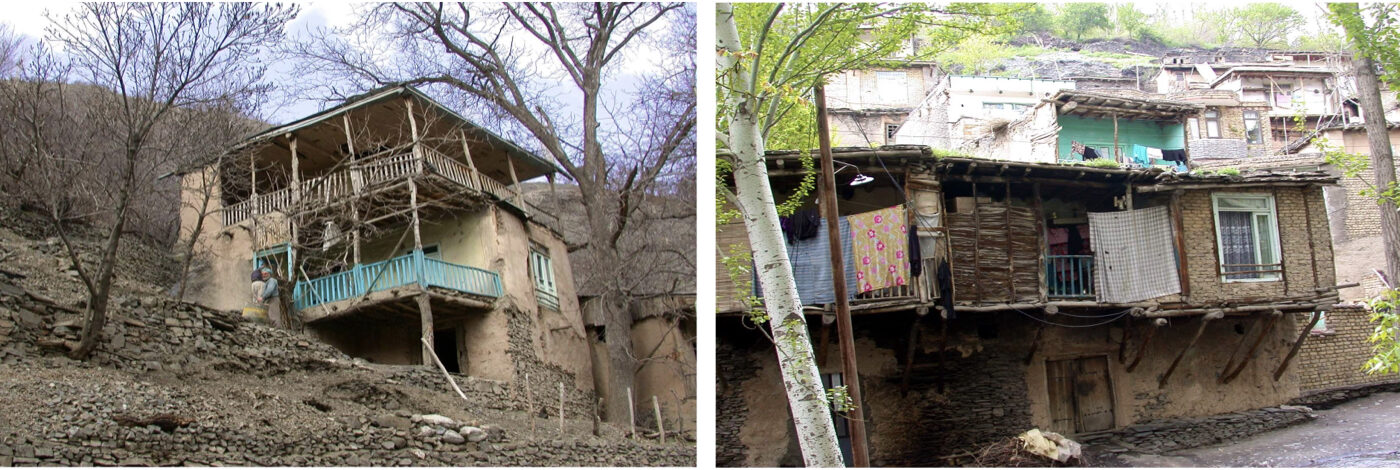

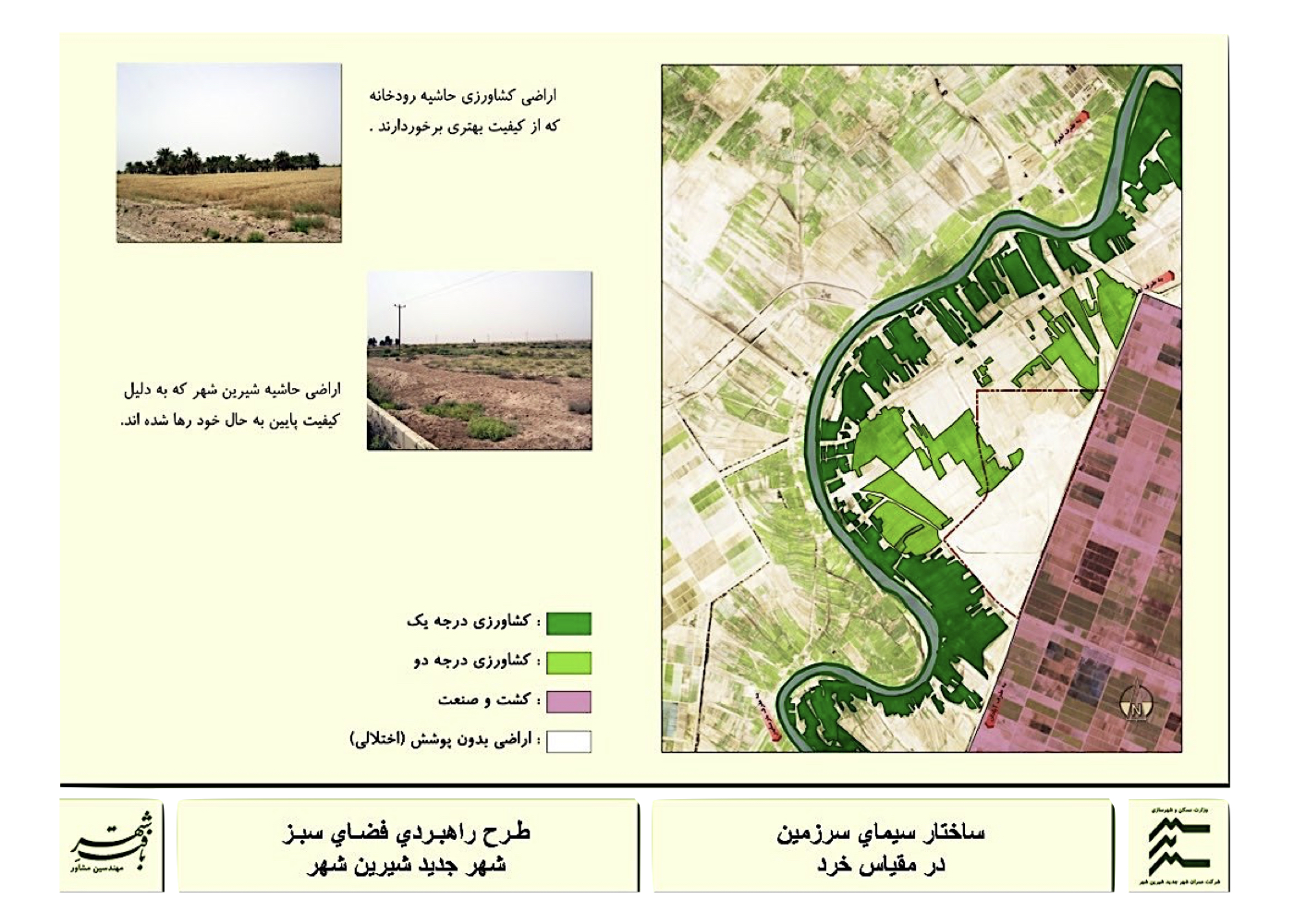

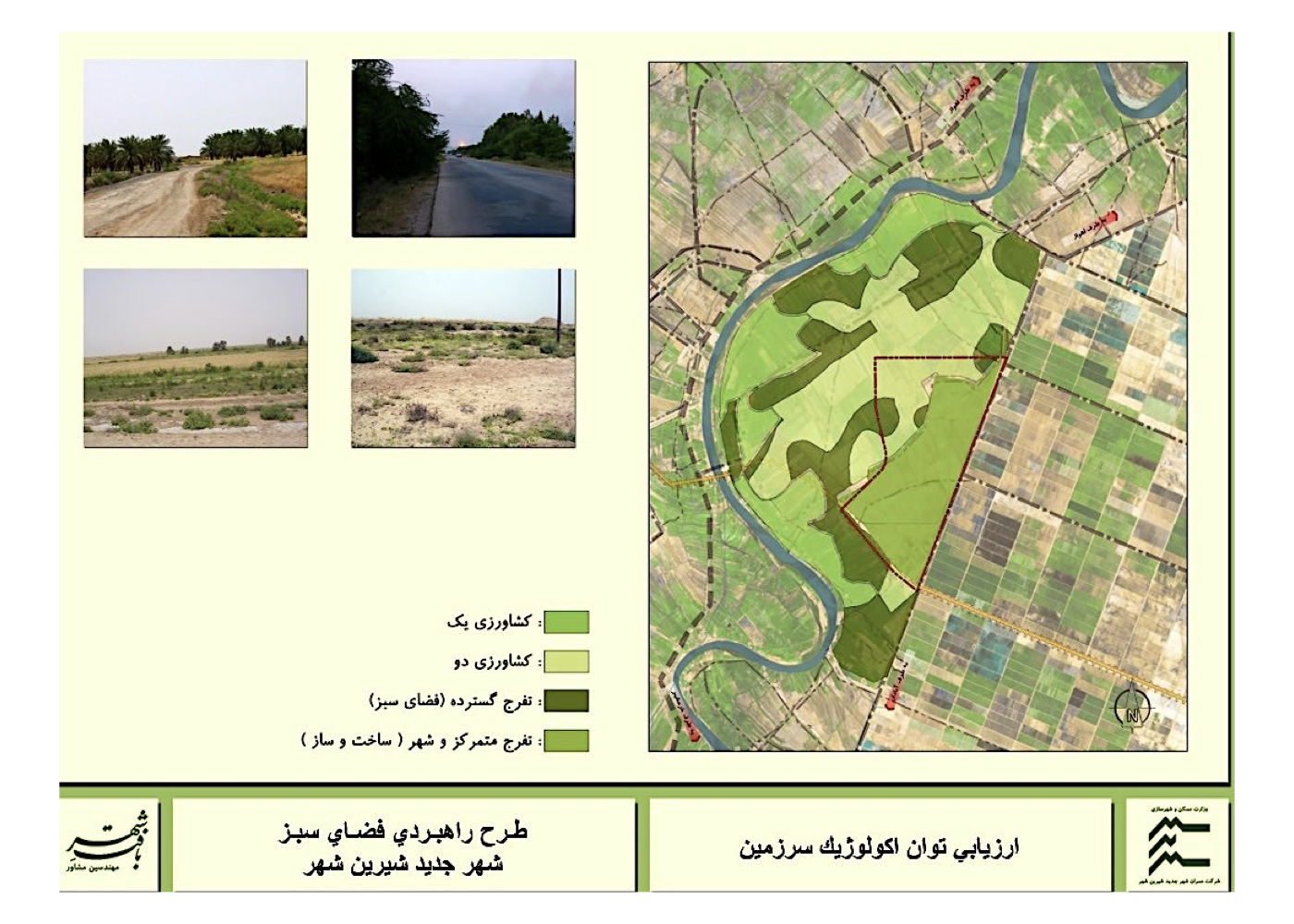

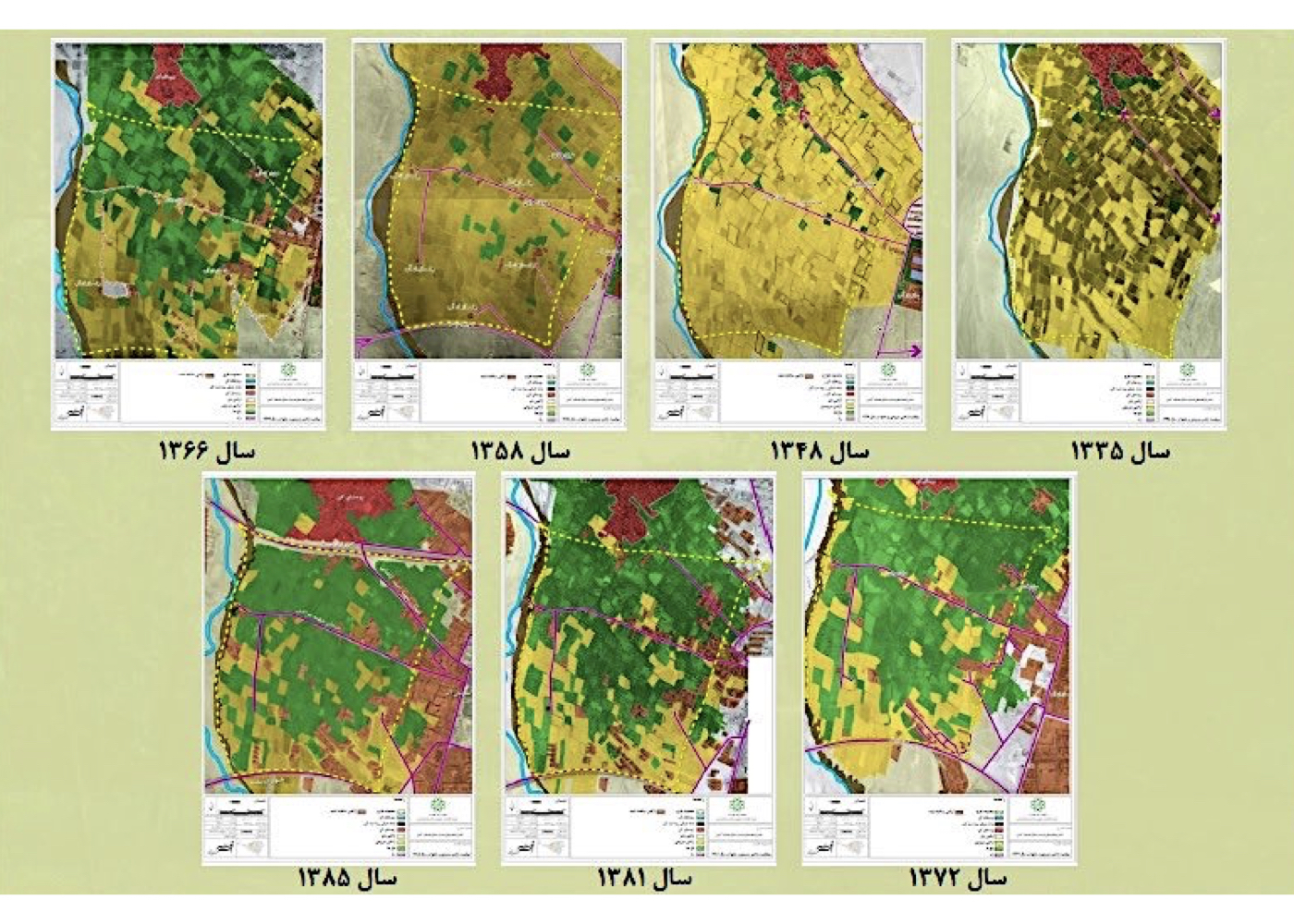

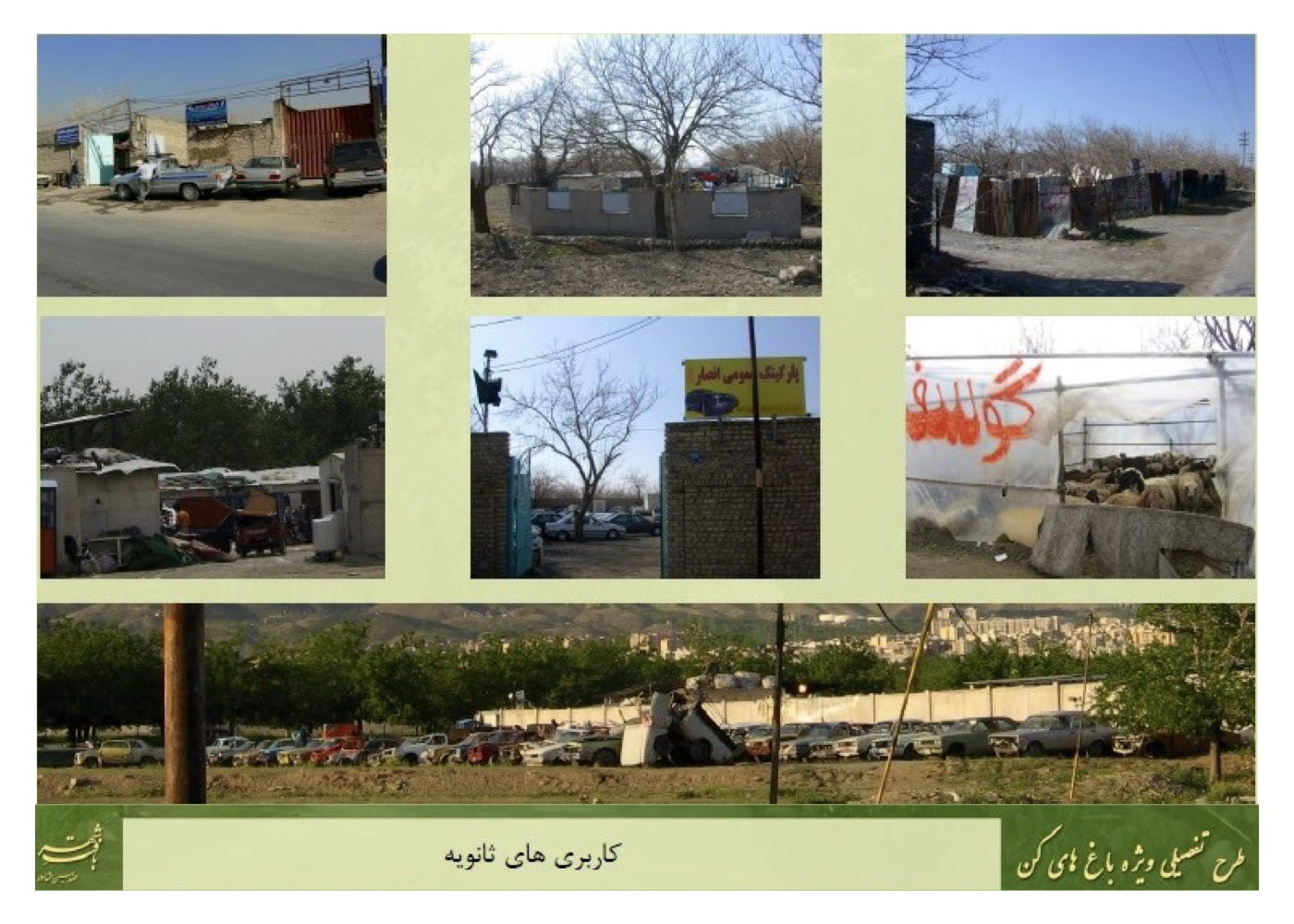

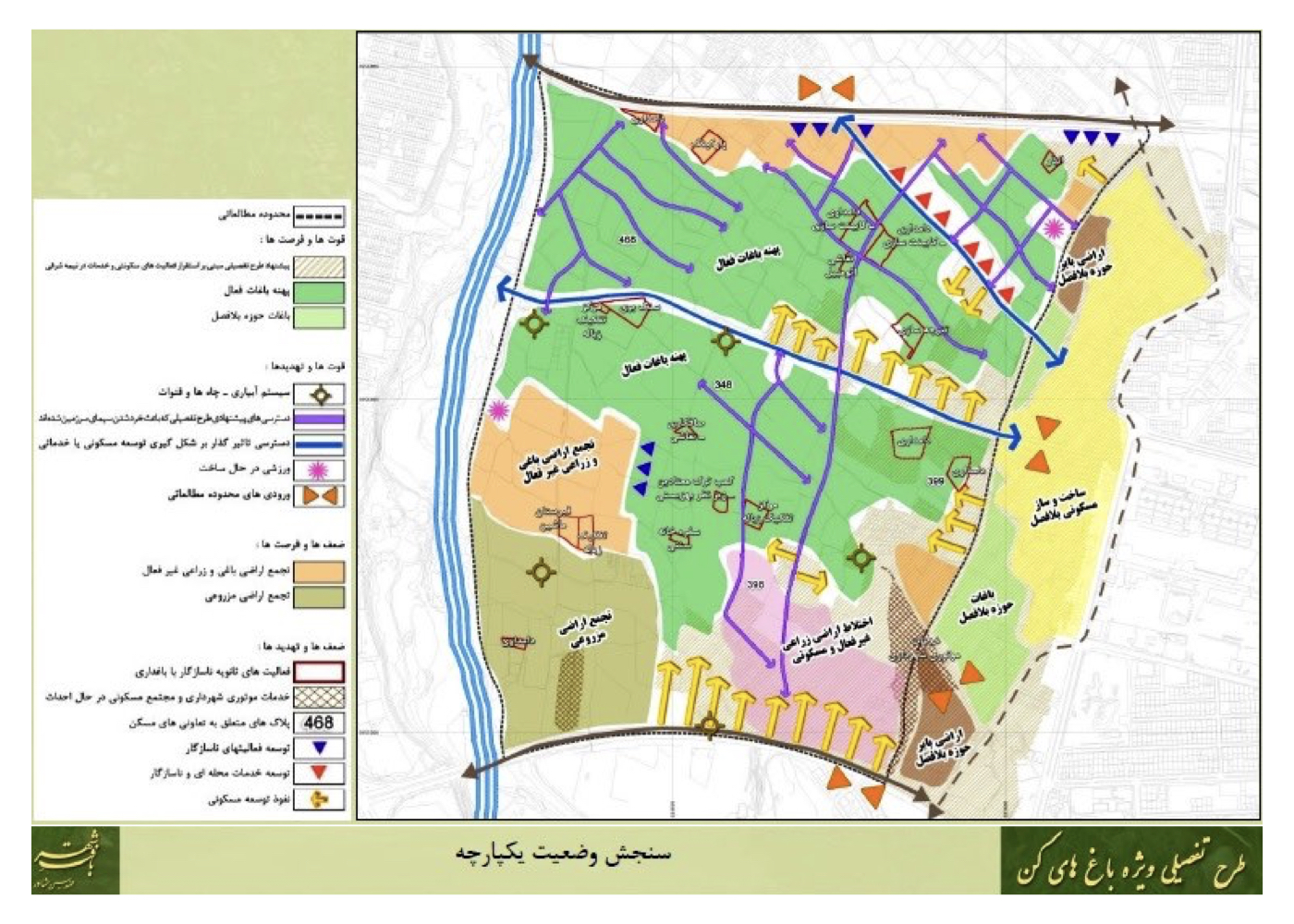

Until the past century, this balanced and sustainable relationship between city, people, and nature endured across our land. However, in recent decades, urban development plans have prioritized physical expansion, neglecting foresighted strategies to protect cities’ natural treasures. Especially in the last four decades, due to shortsighted and profit-driven management, the destruction of these valuable resources has accelerated. Examples include:

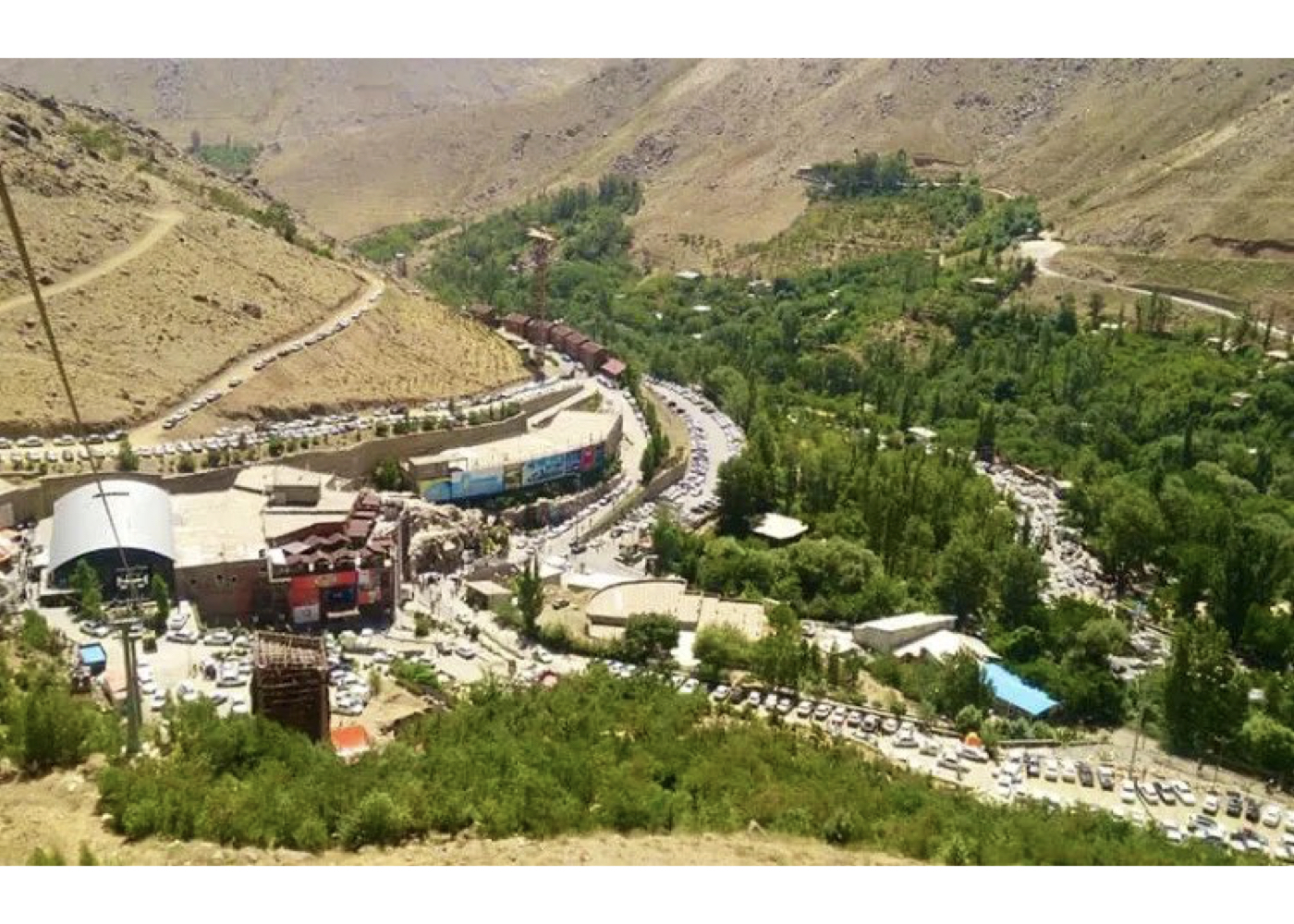

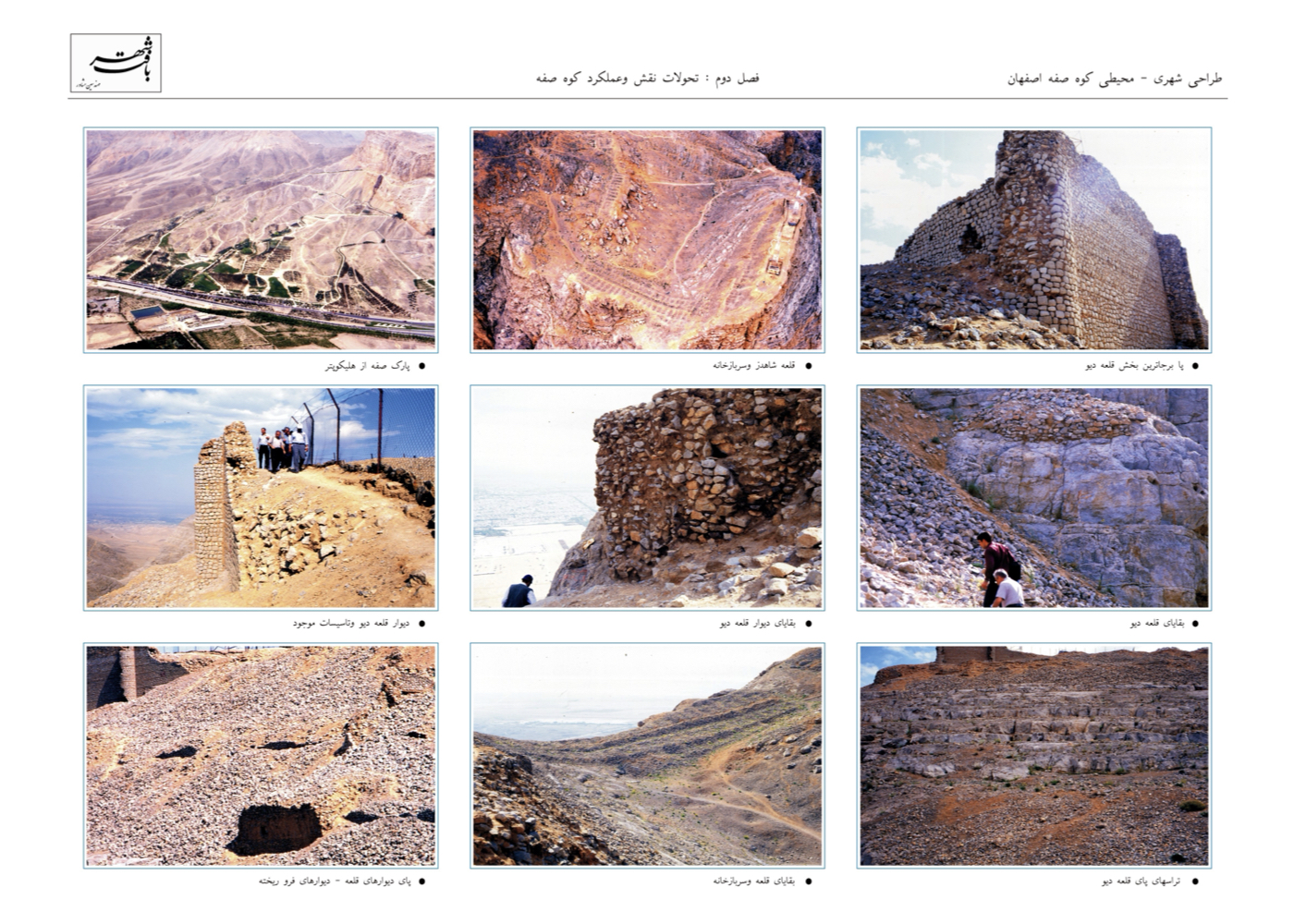

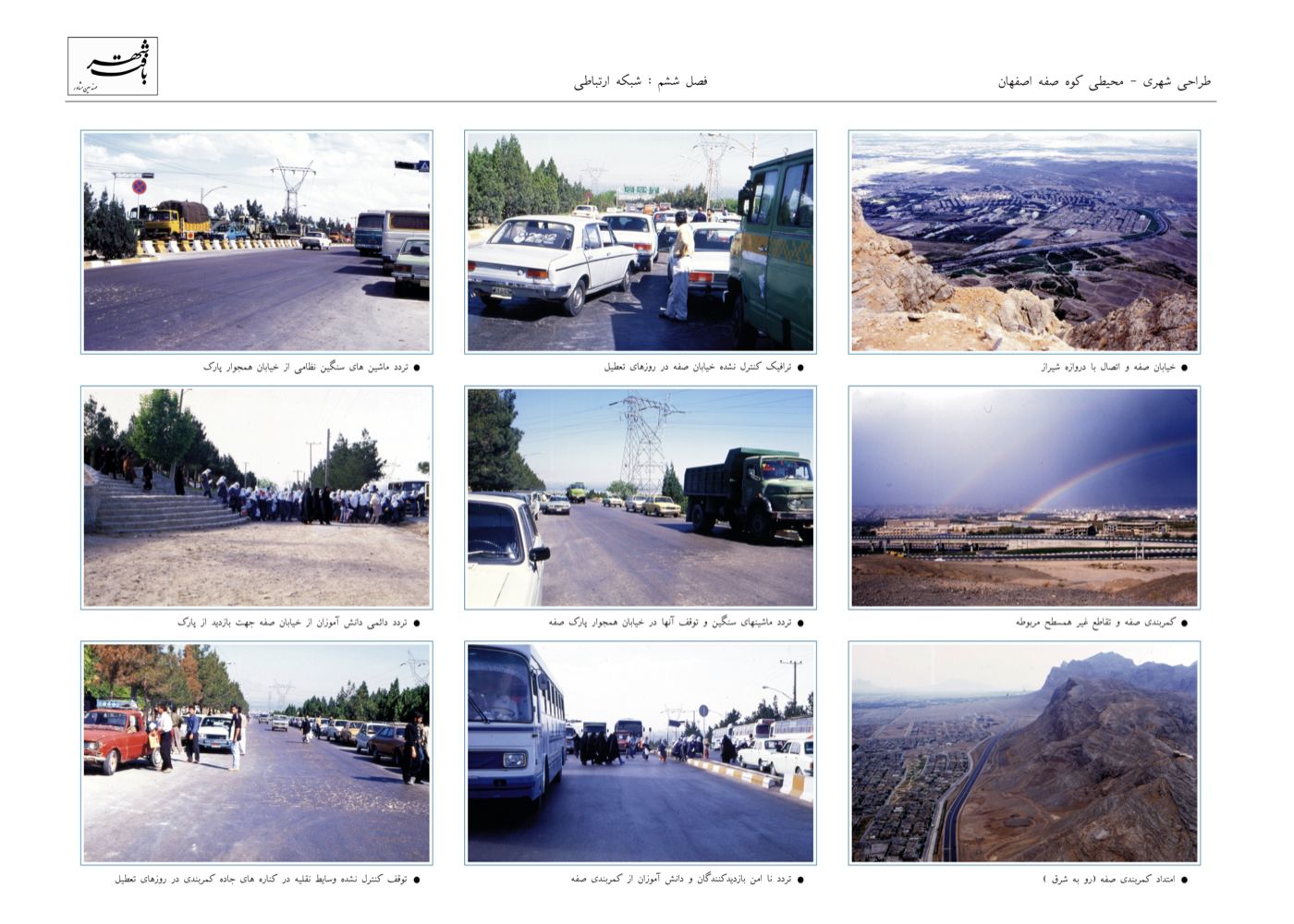

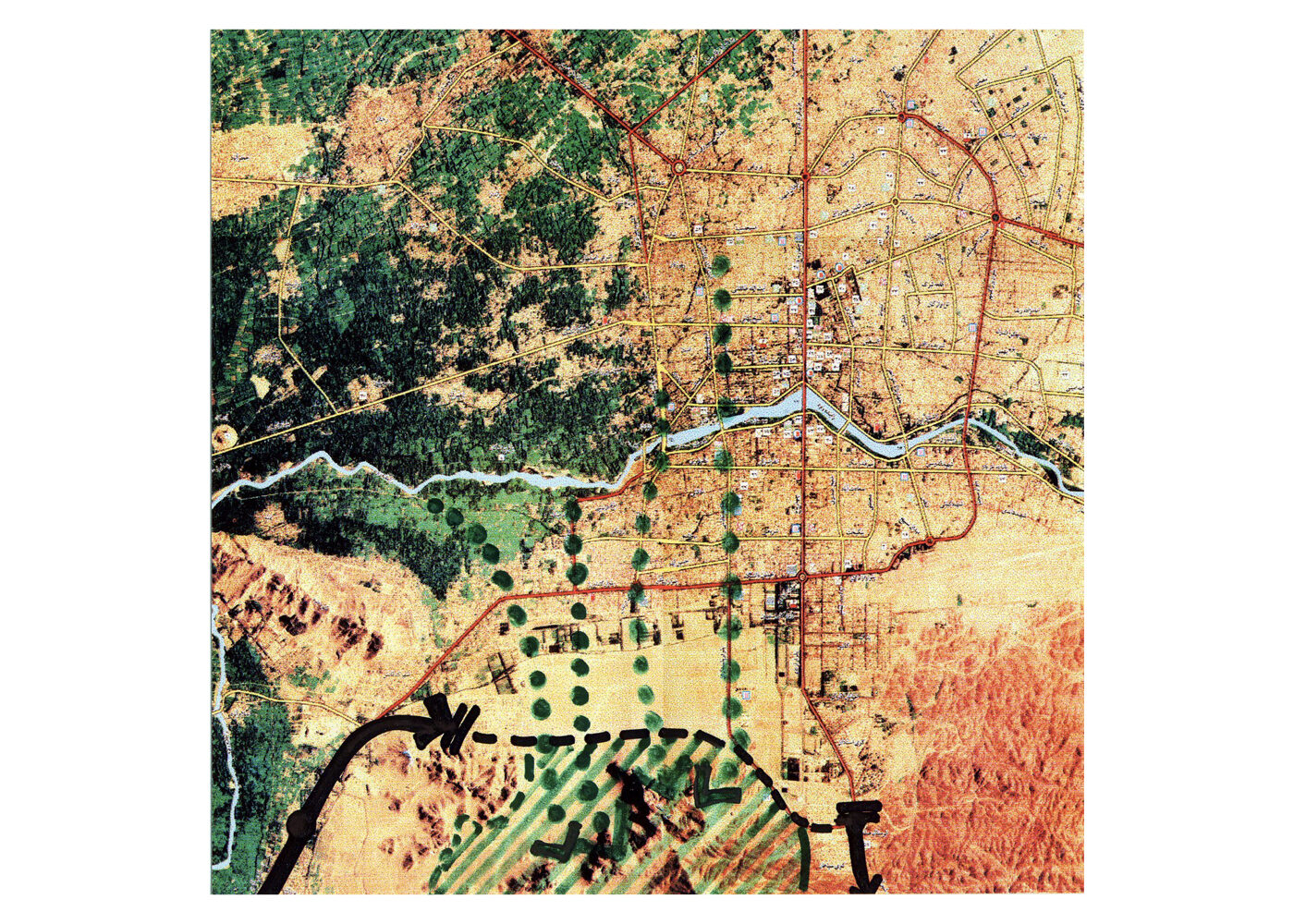

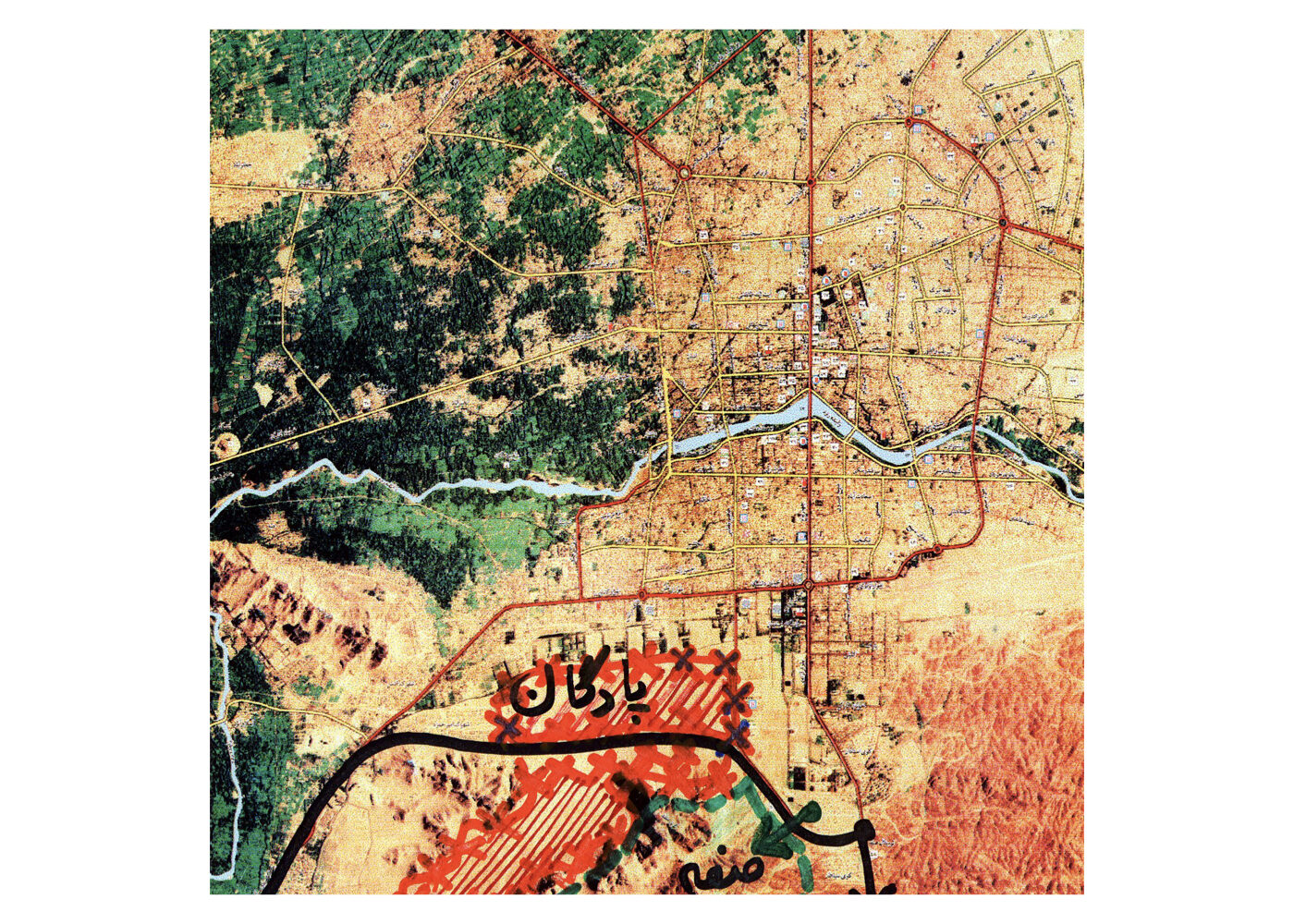

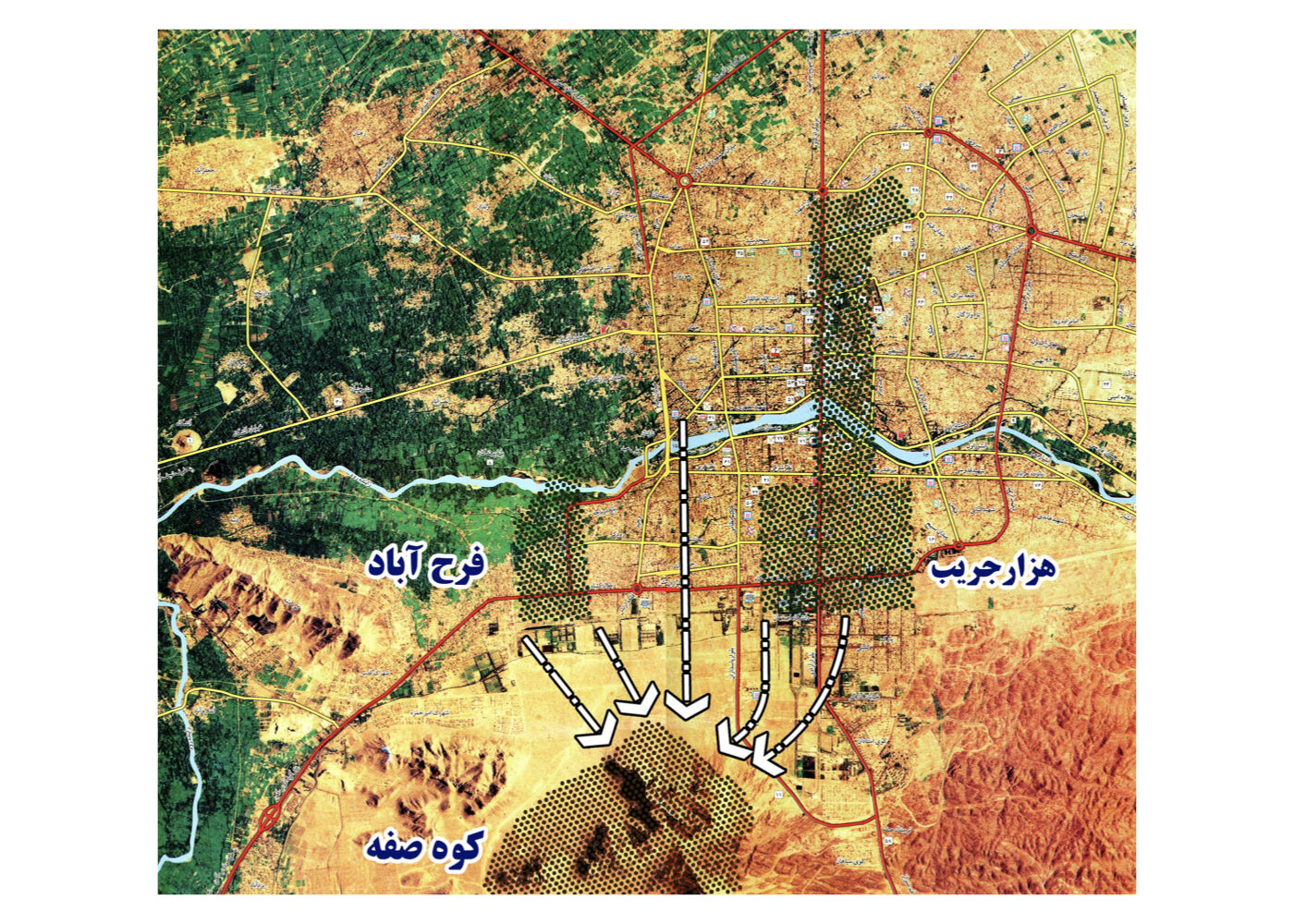

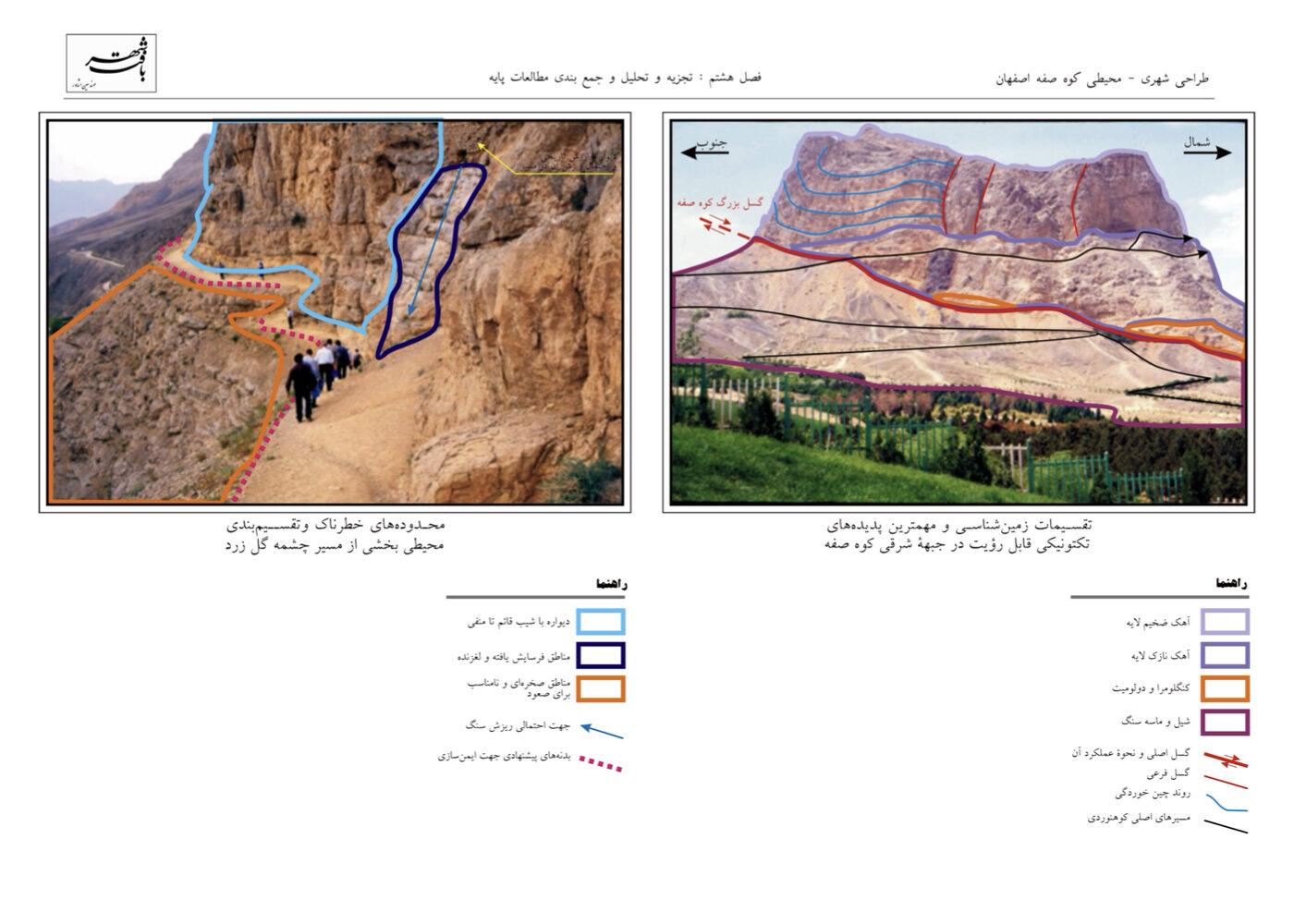

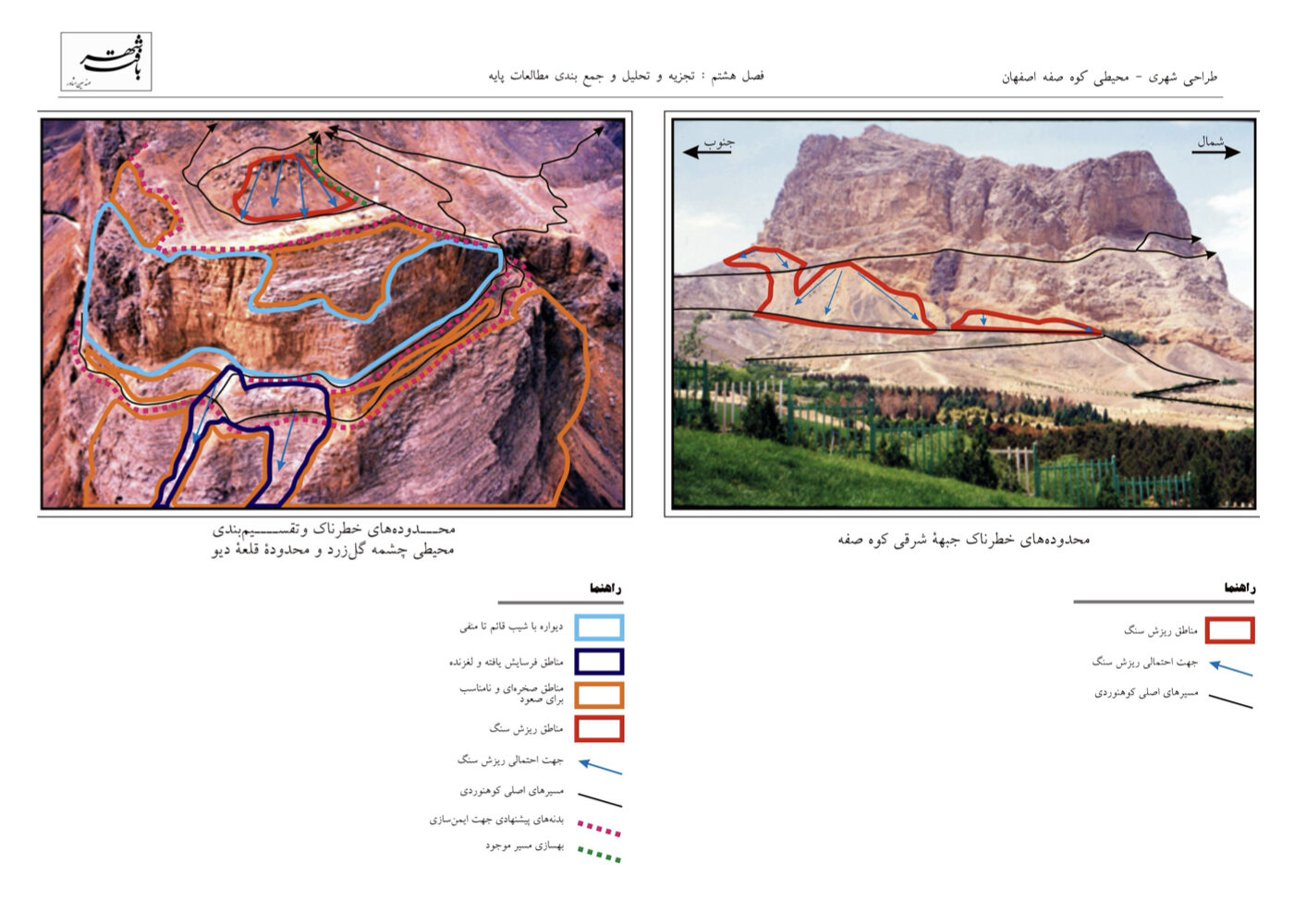

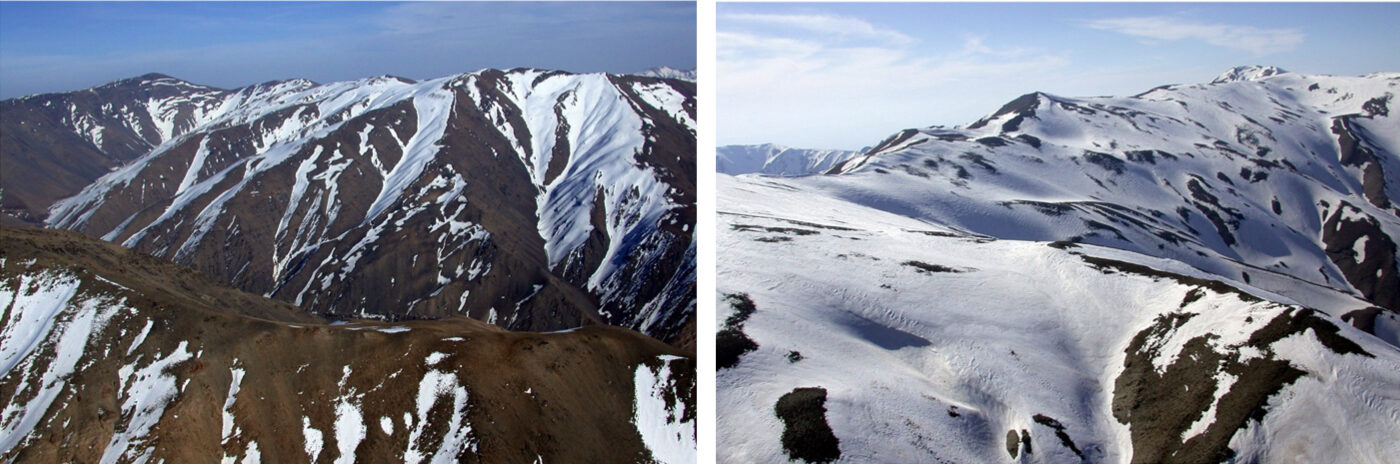

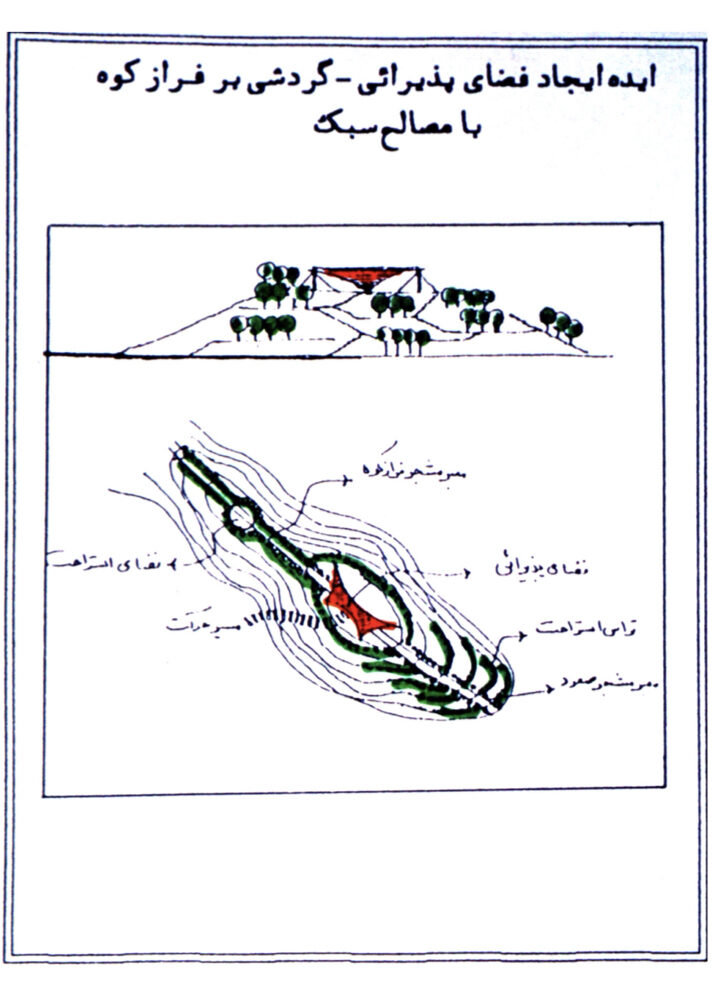

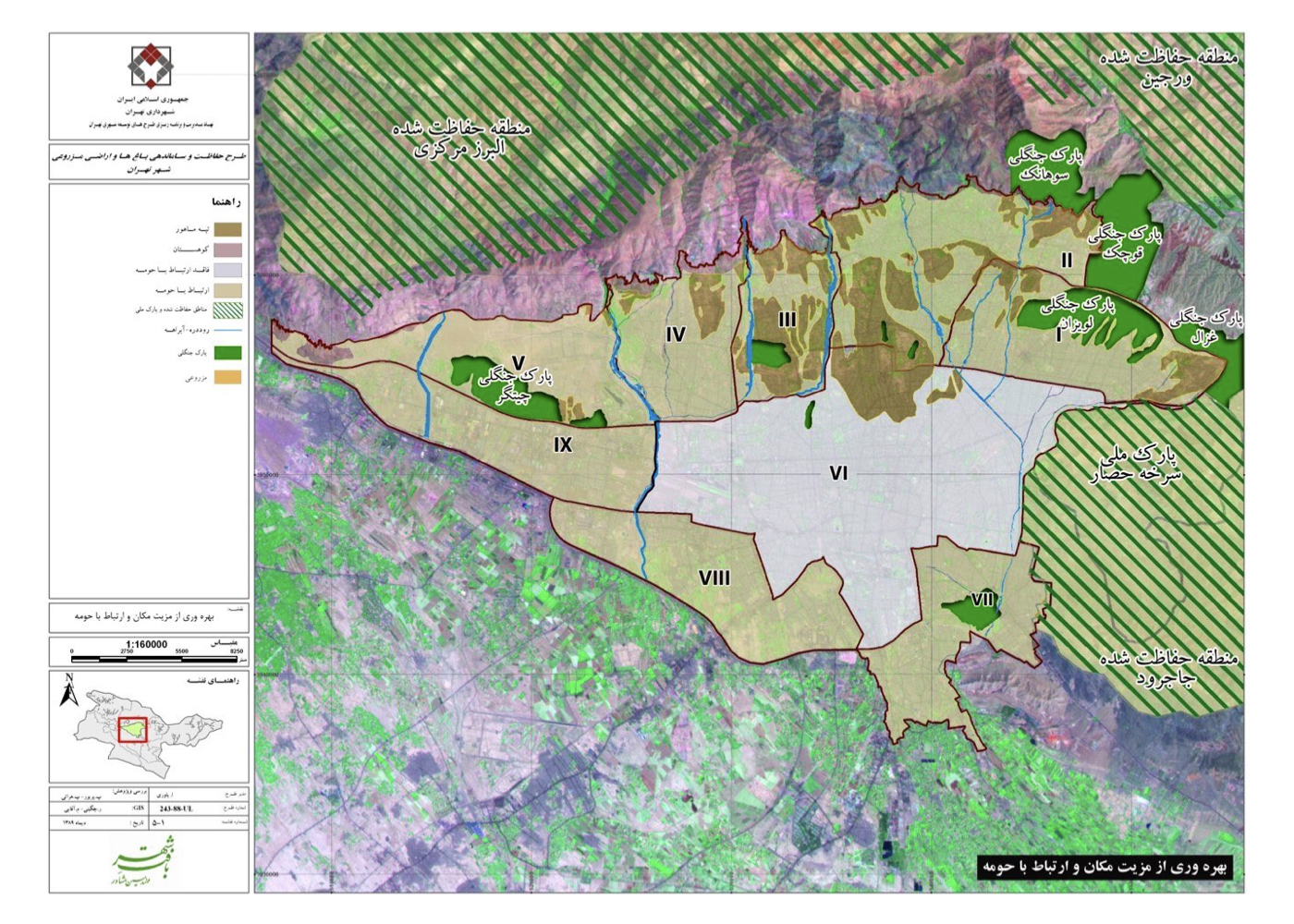

Mountains and hills: For urban expansion, these were designated for military, recreational, educational, and residential uses. Their slopes were carved for ease of construction, with excavated soil dumped into valleys and lowlands.

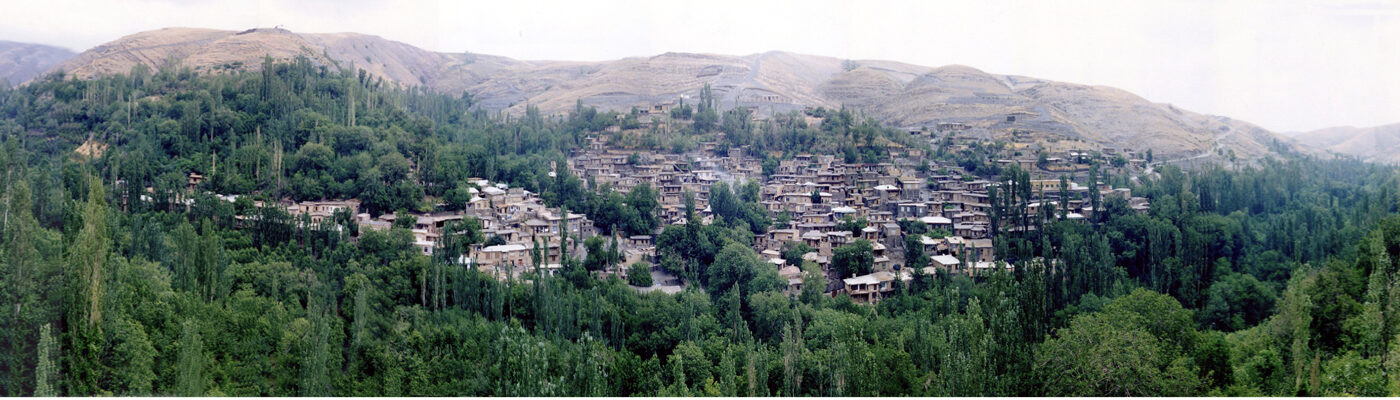

Foothill lands: Absorbed into the expanding urban fabric.

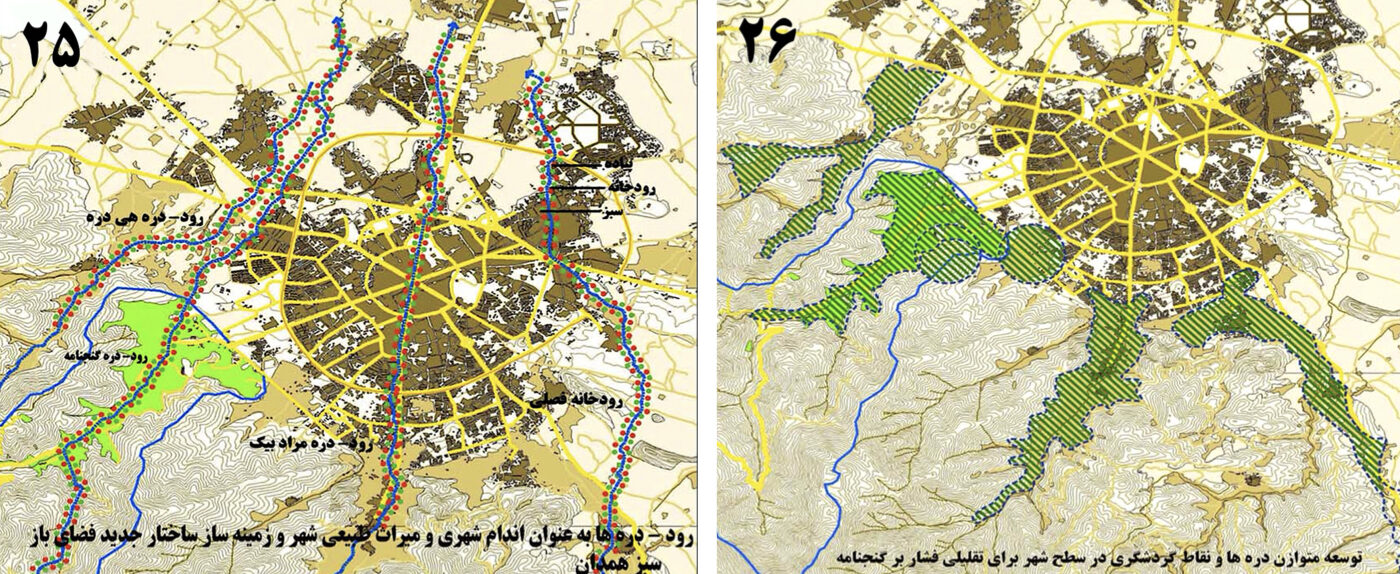

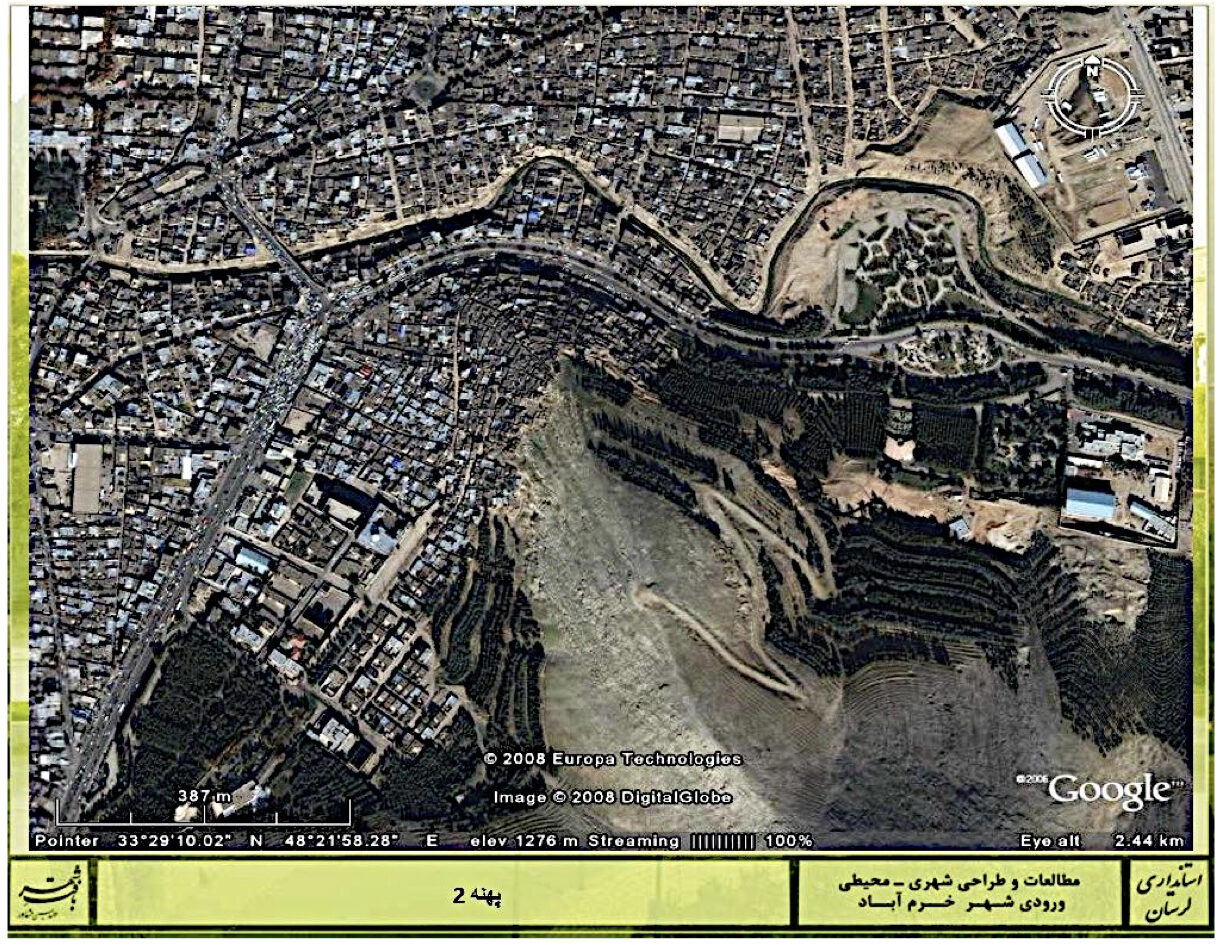

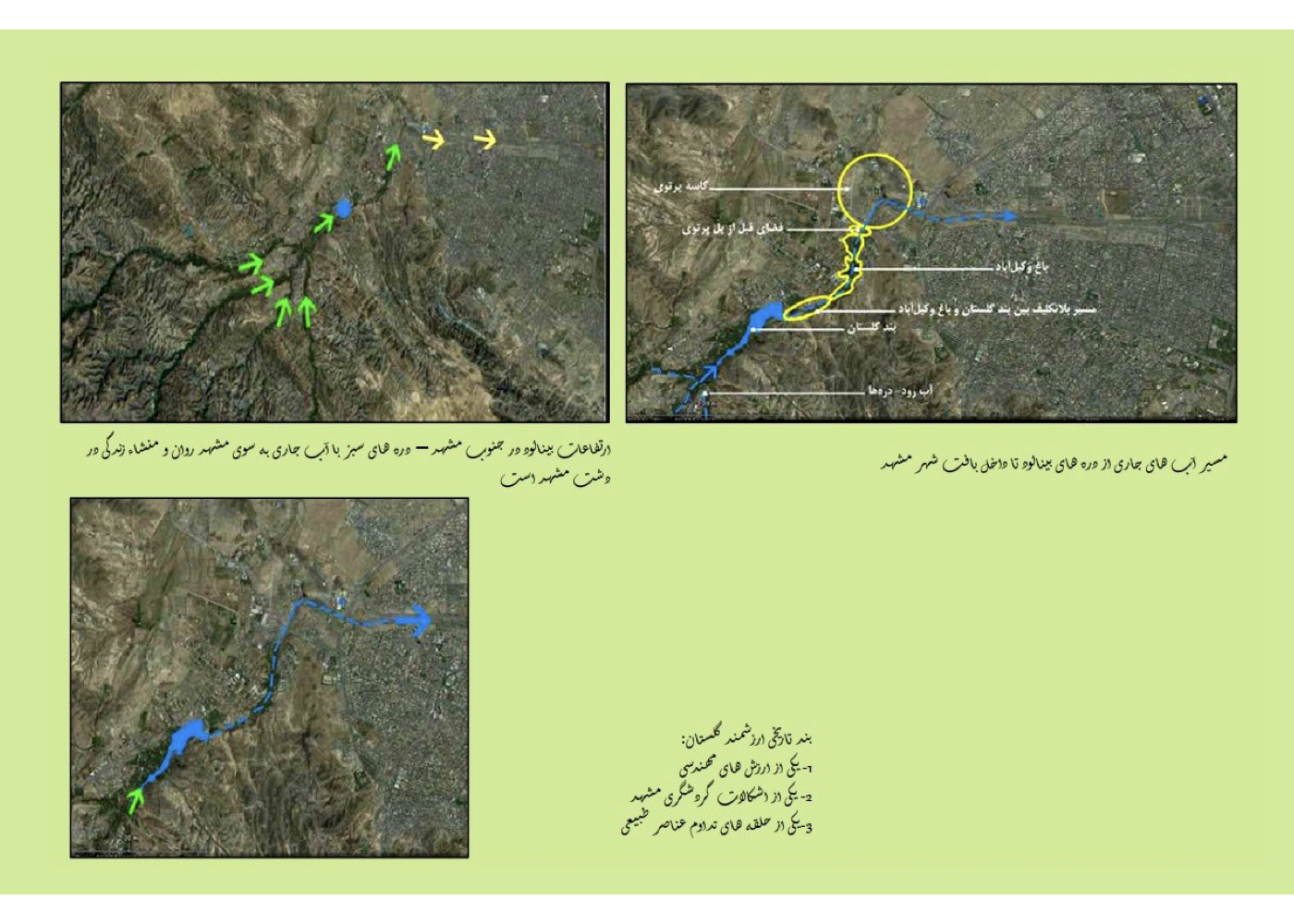

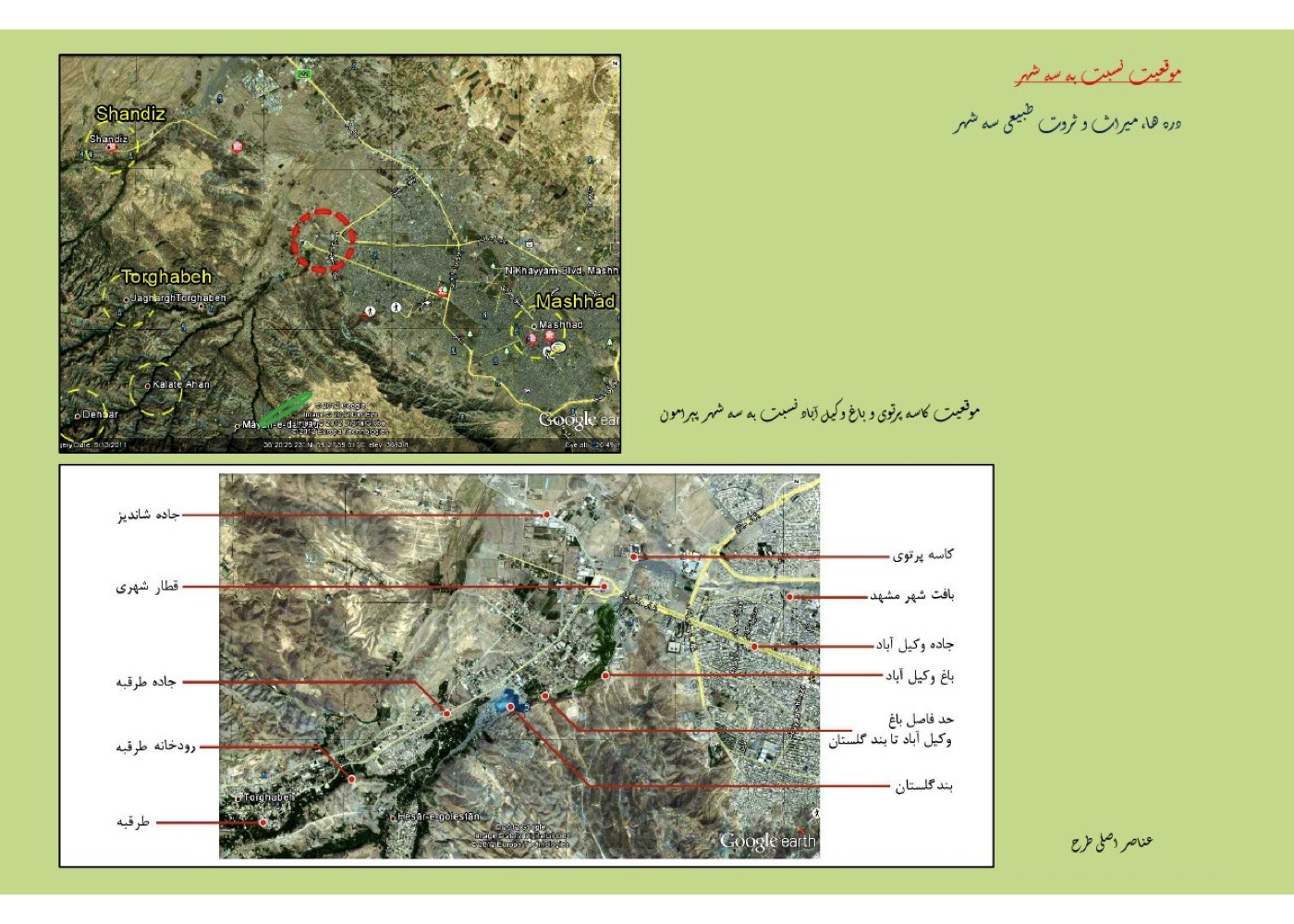

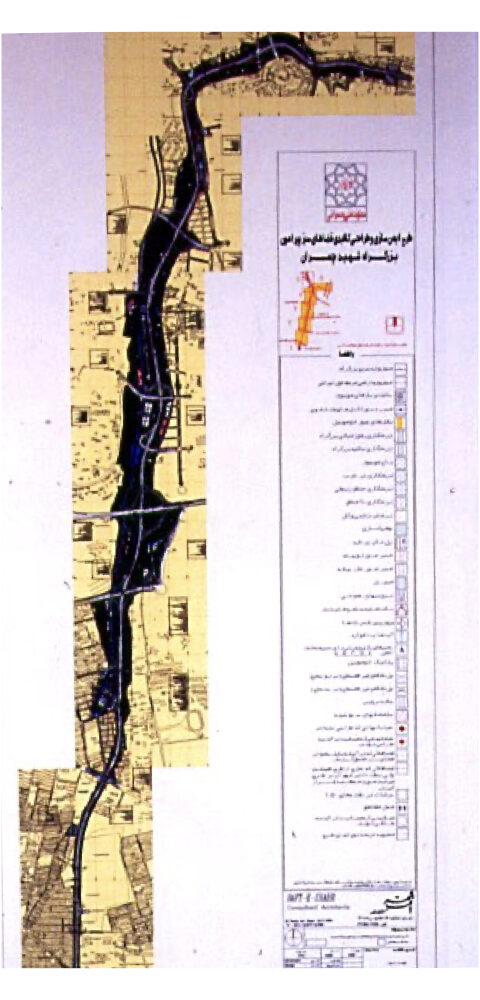

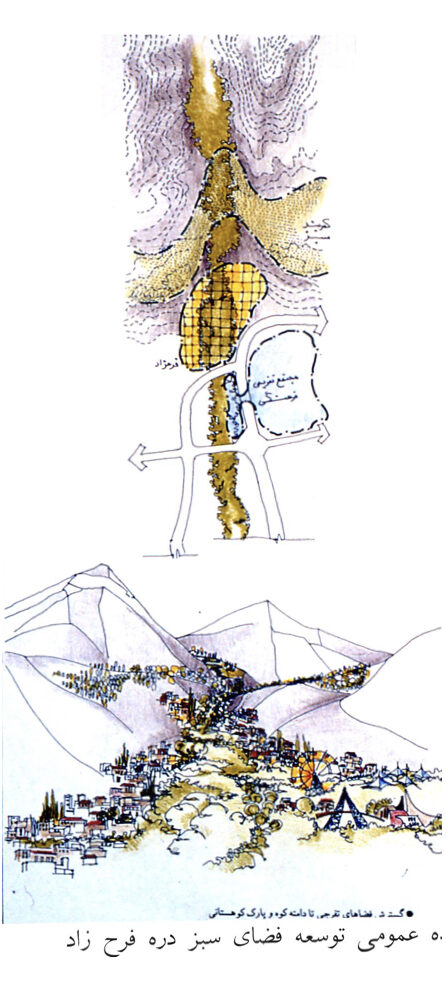

Valleys and their surroundings:Due to fertile soil and water access, initially transformed into private gardens, then into garden-villas, and ultimately apartment complexes.

Waterways: Filled with debris from hill excavation or eroded into instability.

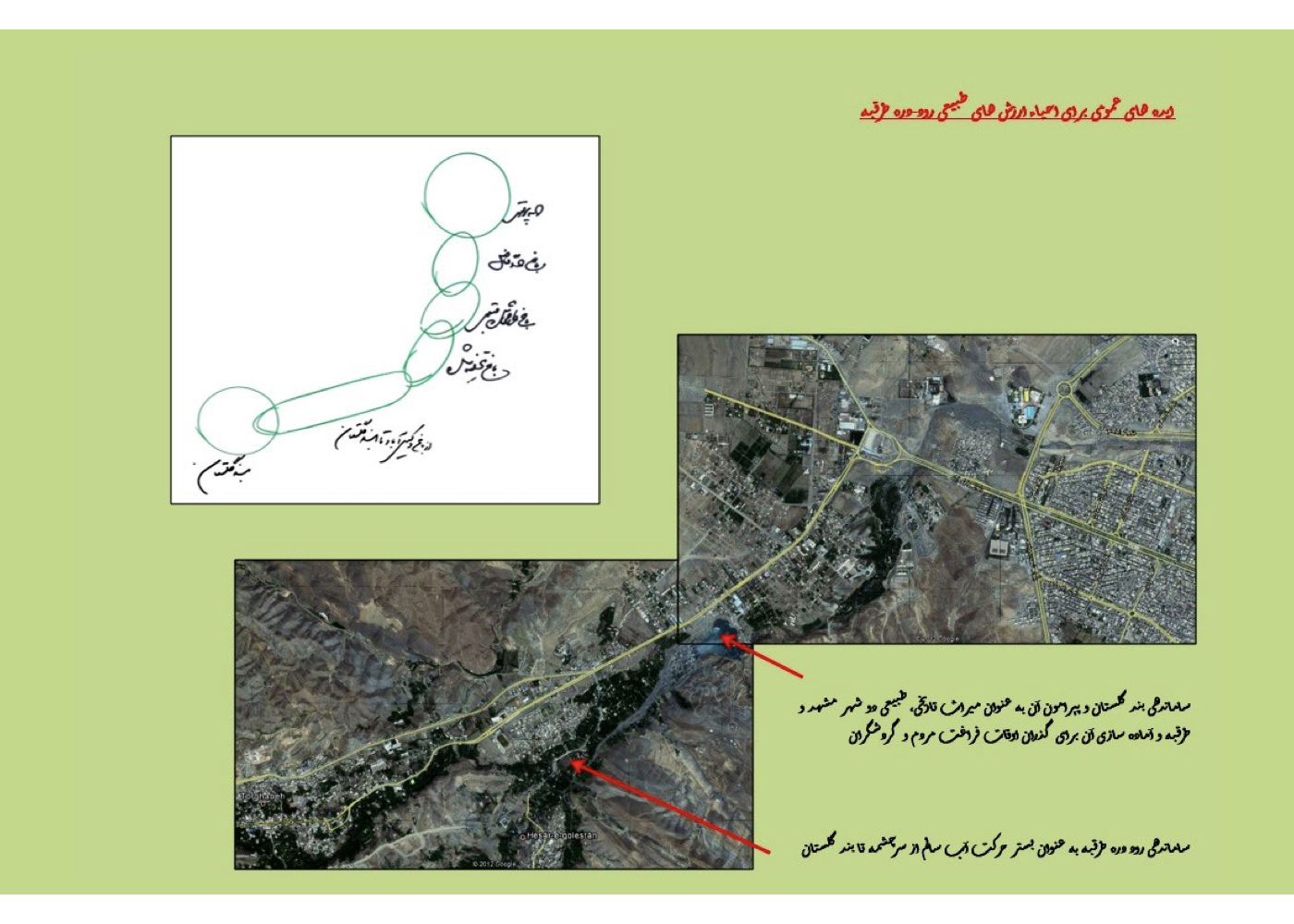

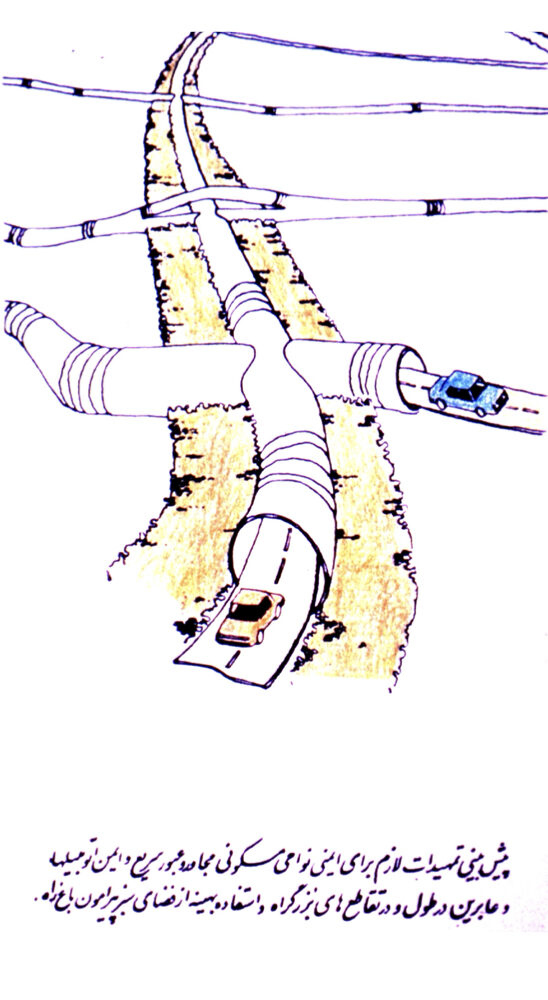

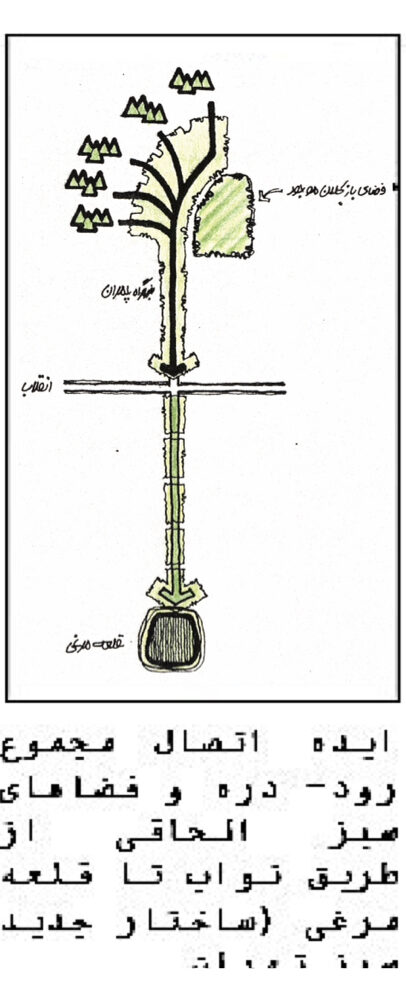

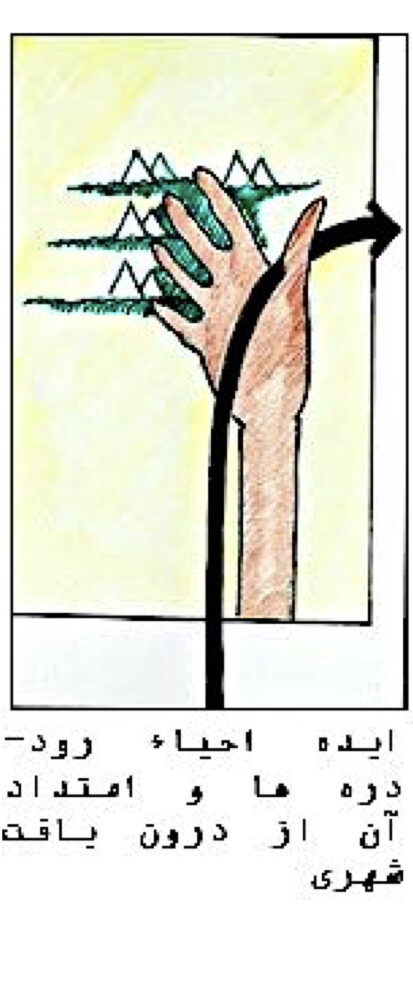

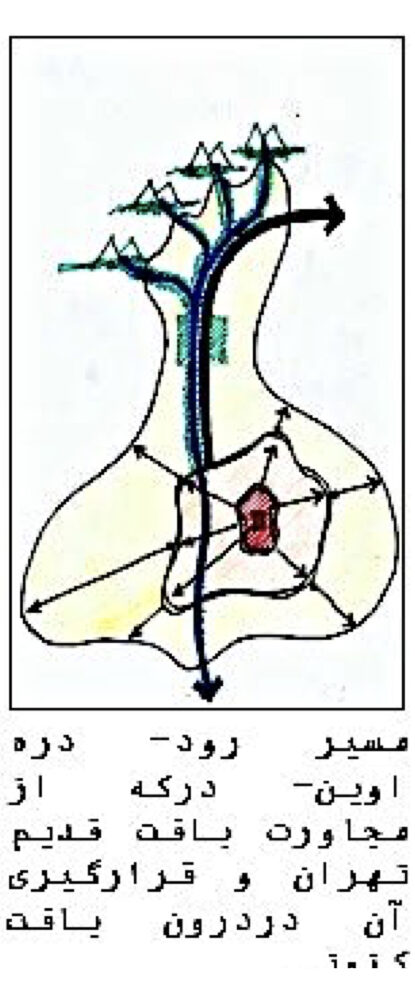

River-valleys: By enforcing regulations without environmental considerations (lacking a forward-looking perspective on the environment), their natural beds were replaced with concrete channels. These paths turned into waste disposal sites and conduits for polluted water. The remaining land on both sides of the channels was converted into roadways and subsequently sold off.

Rivers:Without complete urban wastewater systems, sewage was discharged directly into rivers, turning them into polluted conduits to lakes and seas.

Springs: Legal and illegal upstream construction has degraded water quality and polluted spring sources.

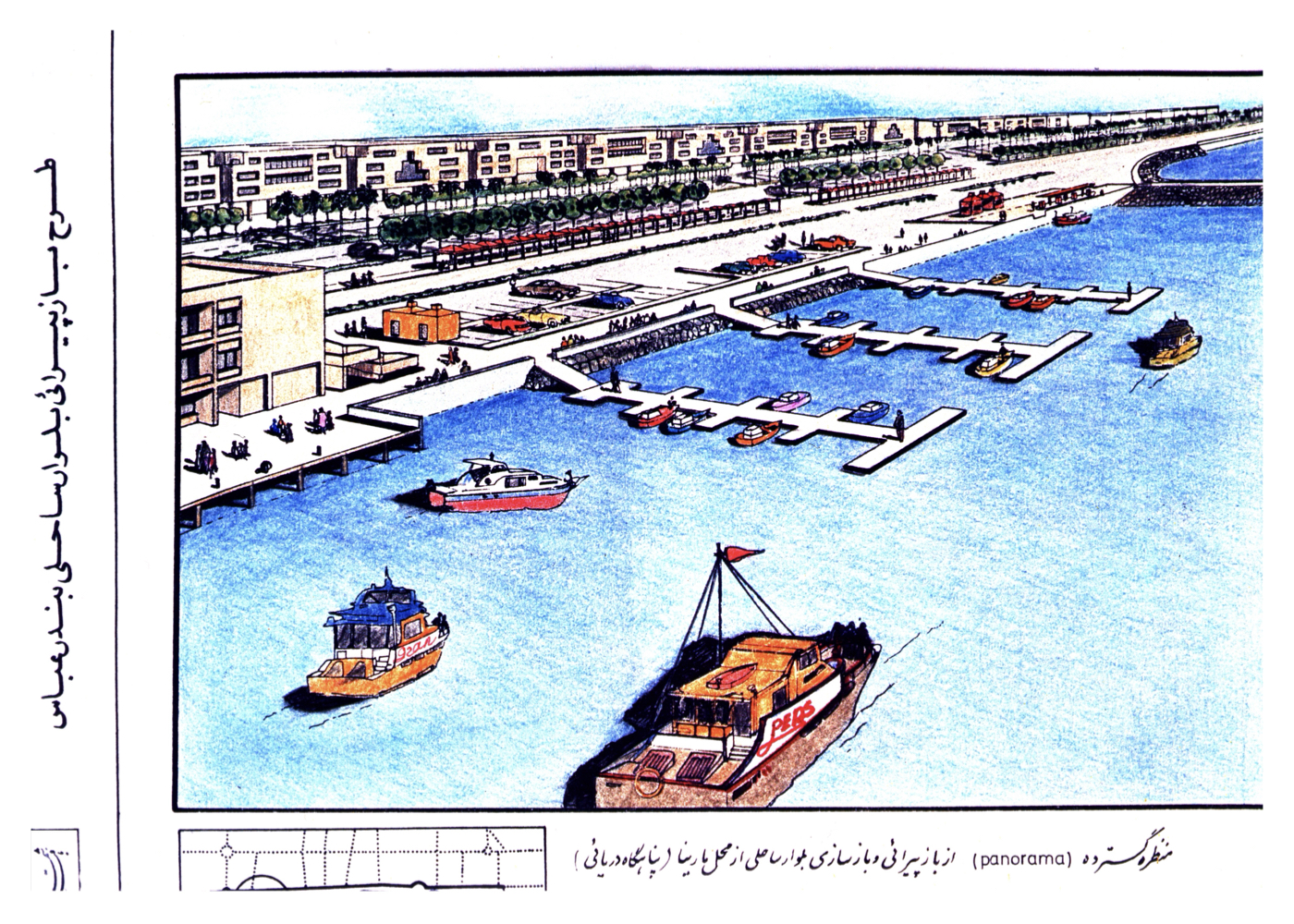

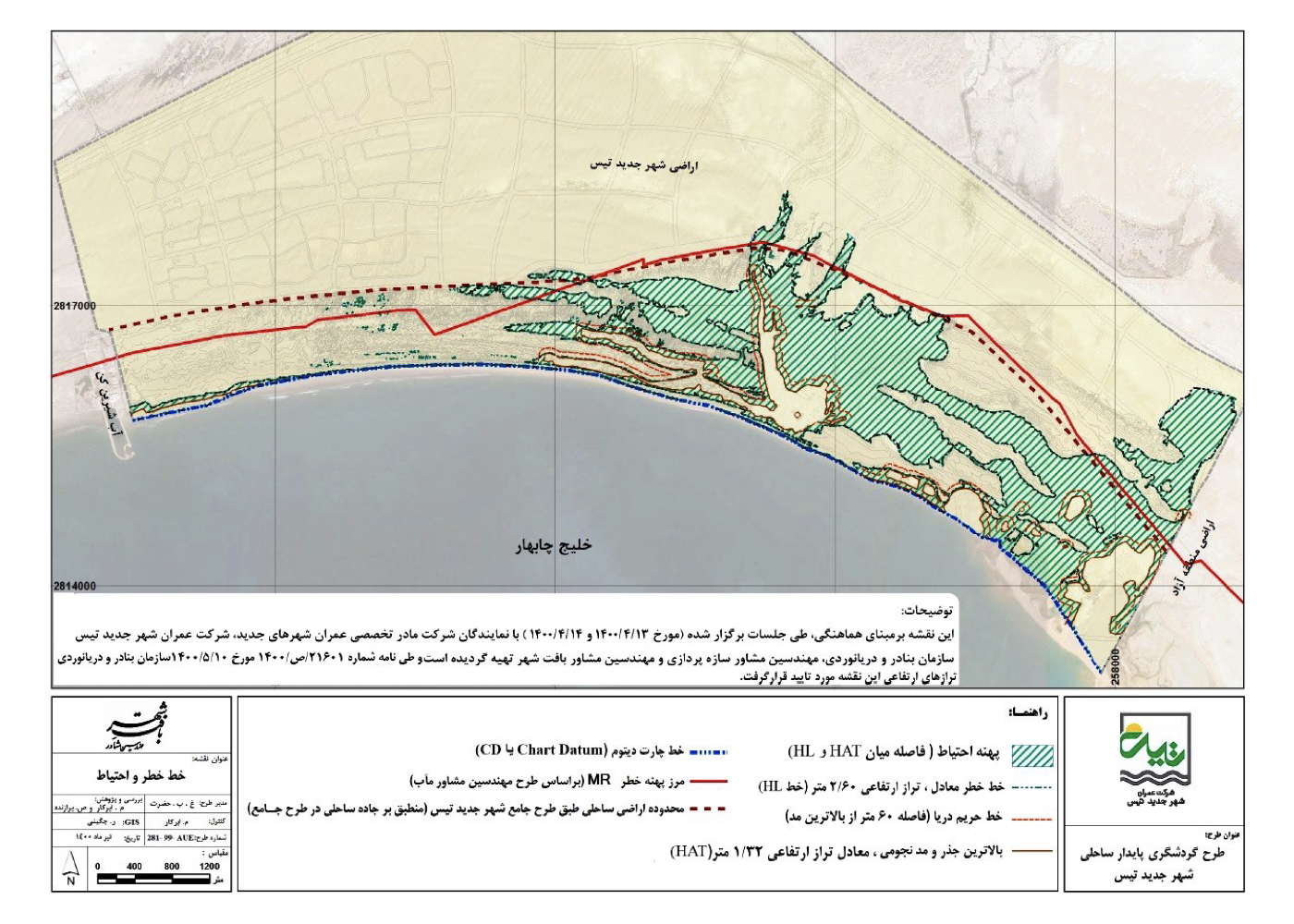

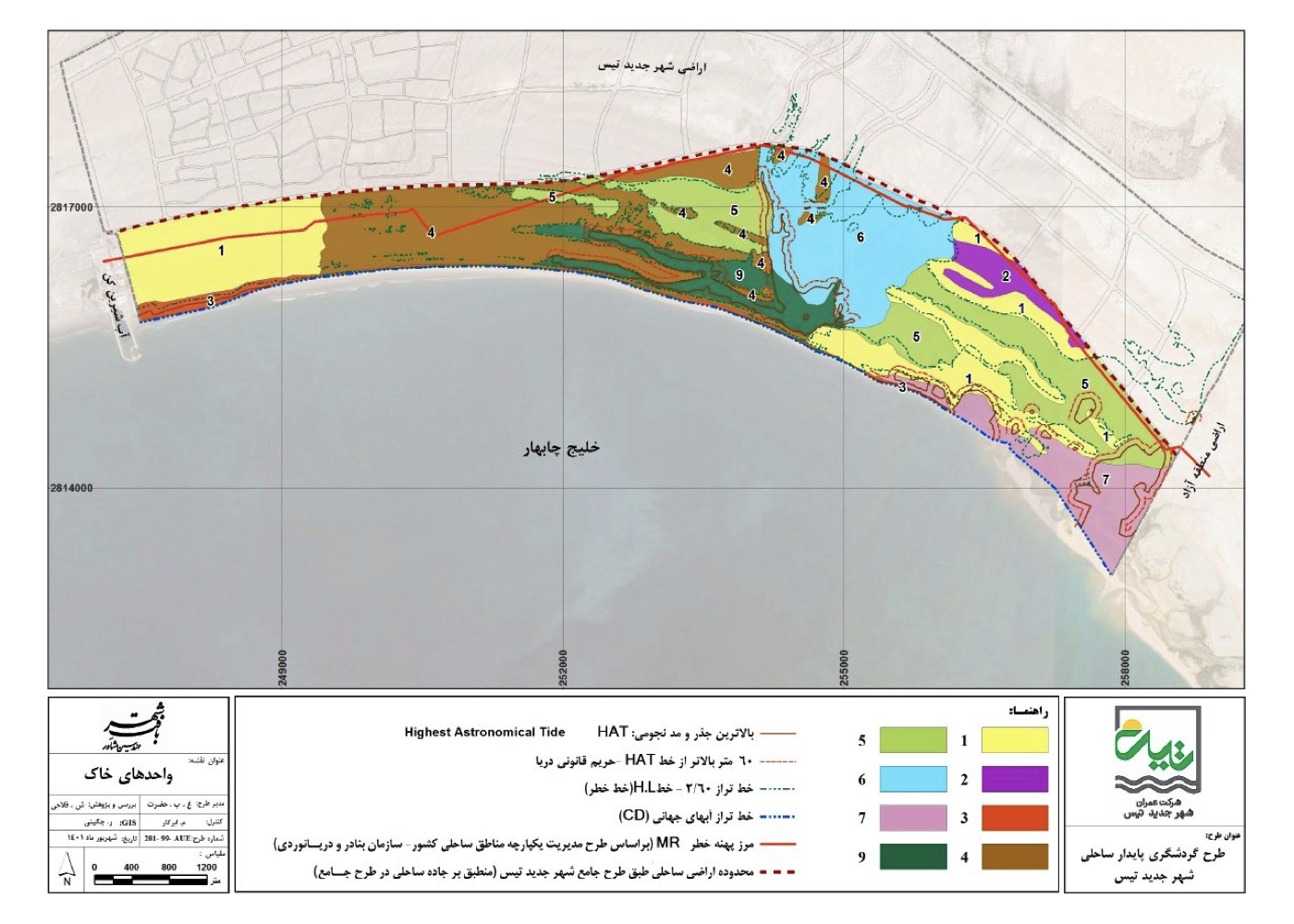

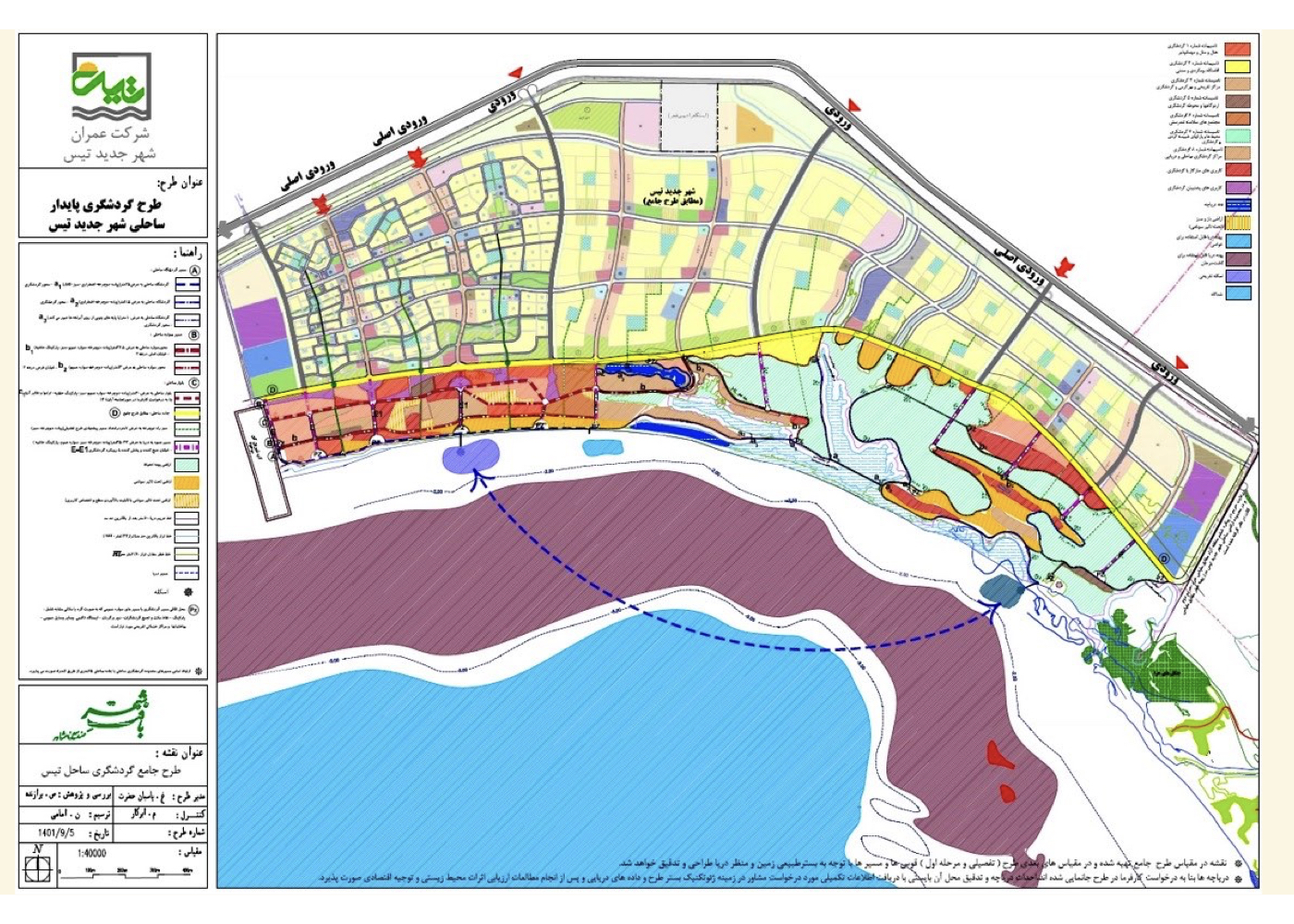

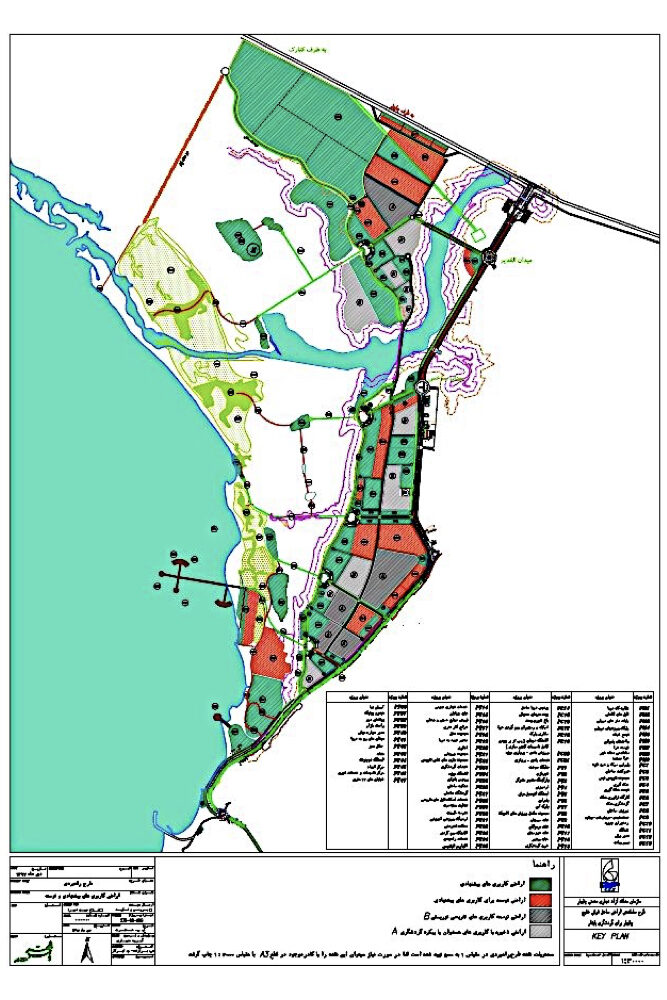

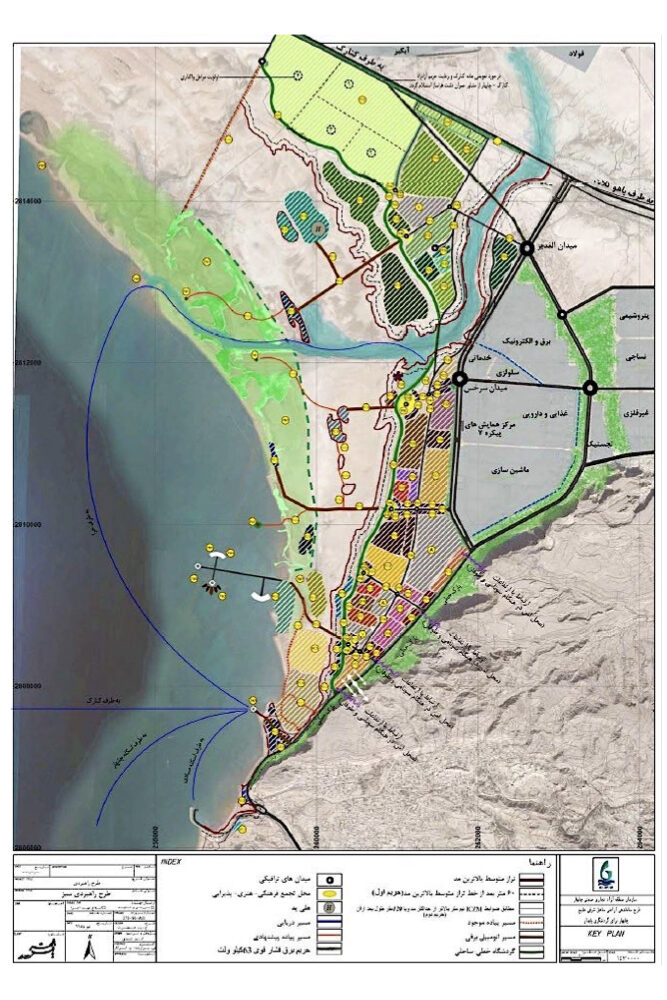

Seas and shorelines: Shores lost their natural purity and value, and the sea was turned into an urban wastewater basin.

Lakes: Unprincipled dam construction has led to the drying of lakes.

Qanats (underground aqueducts): Construction within their protected zones, unauthorized water extraction, sewage discharge, and damage during the development of subways or urban highways led to the destruction of this invaluable engineering heritage passed down from our ancestors.

Groundwater: Highways and tunnels built without accounting for natural underground water paths have blocked or destroyed them.

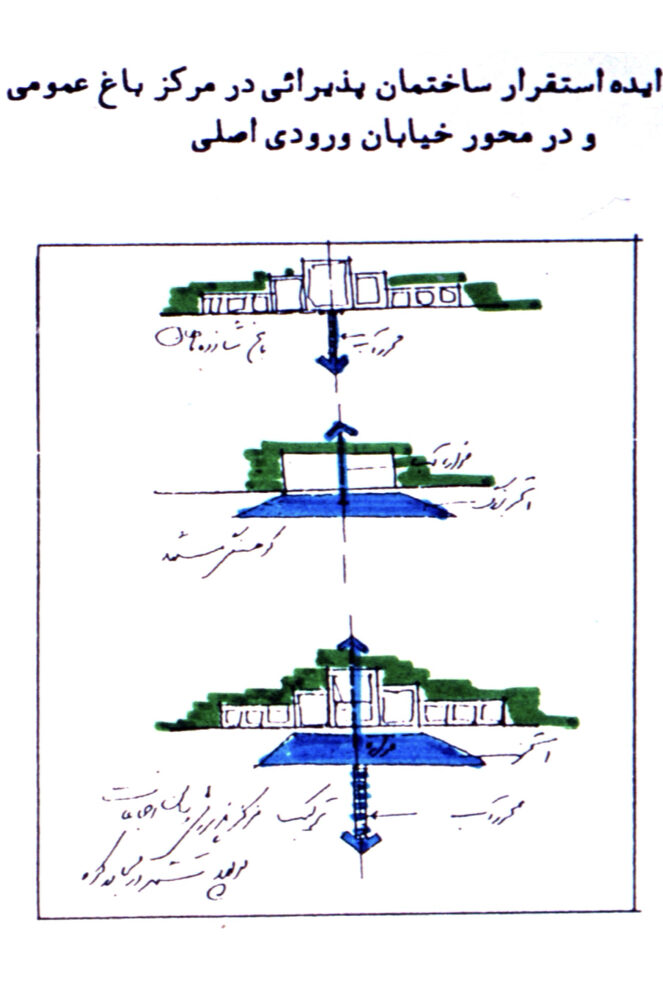

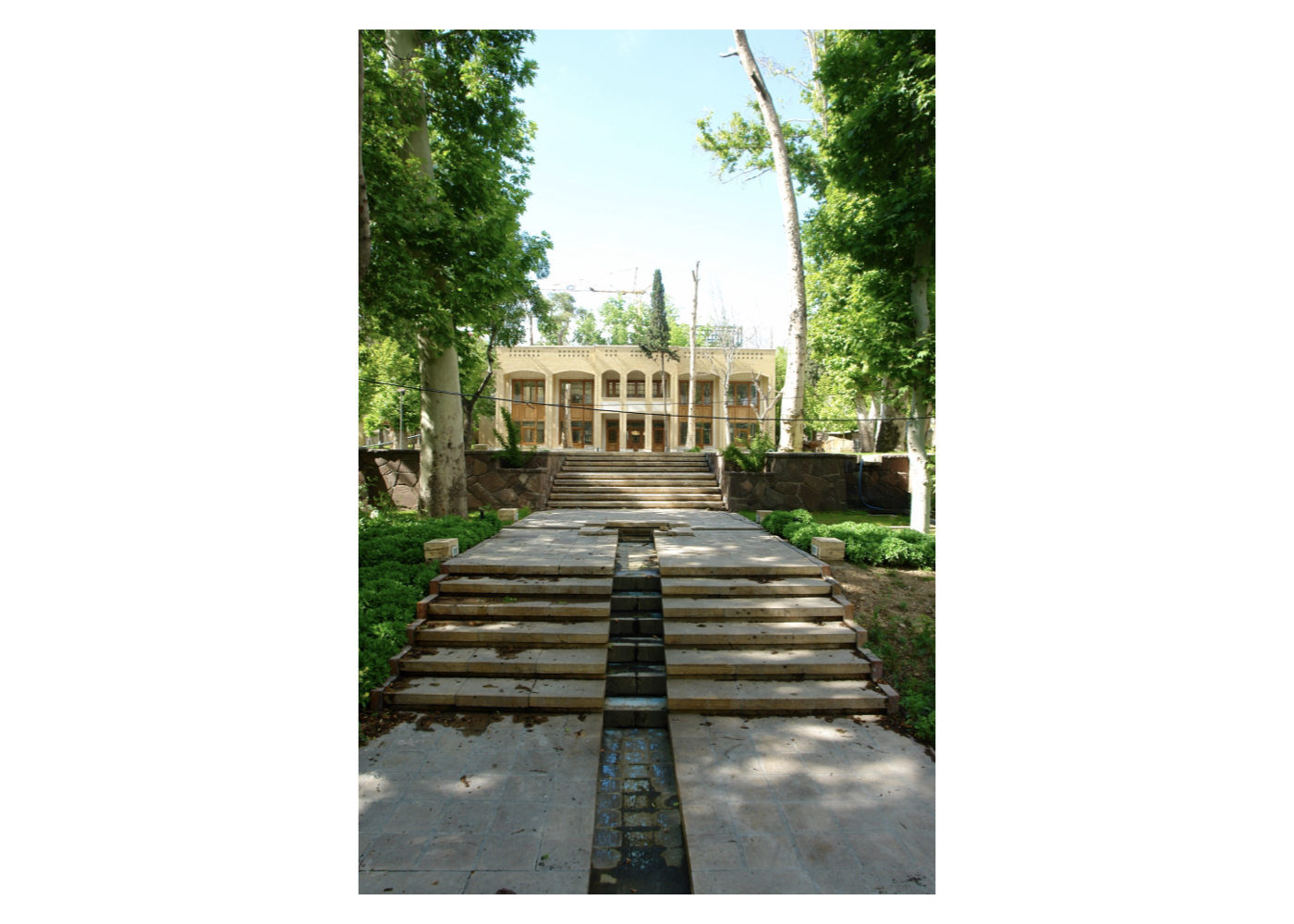

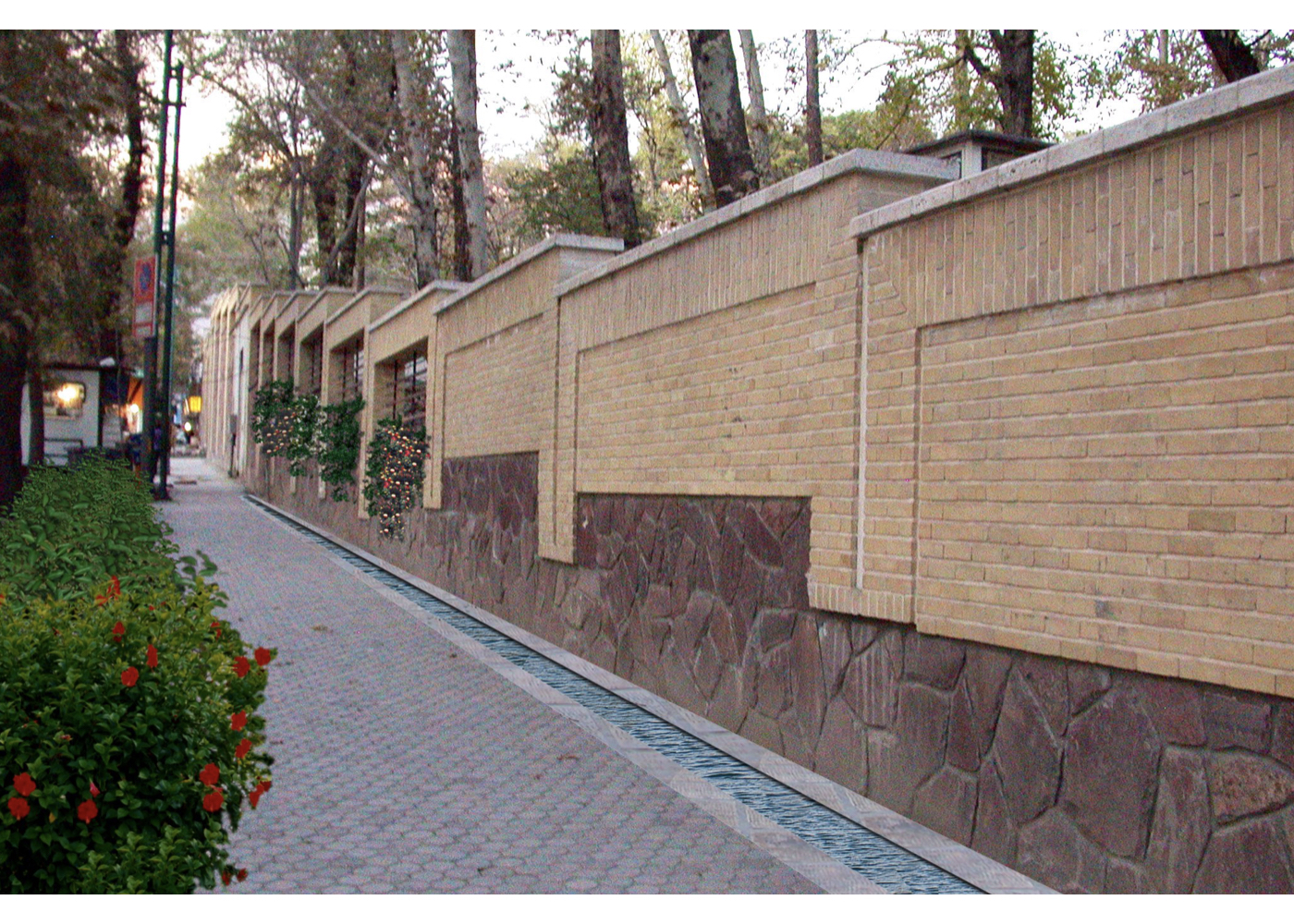

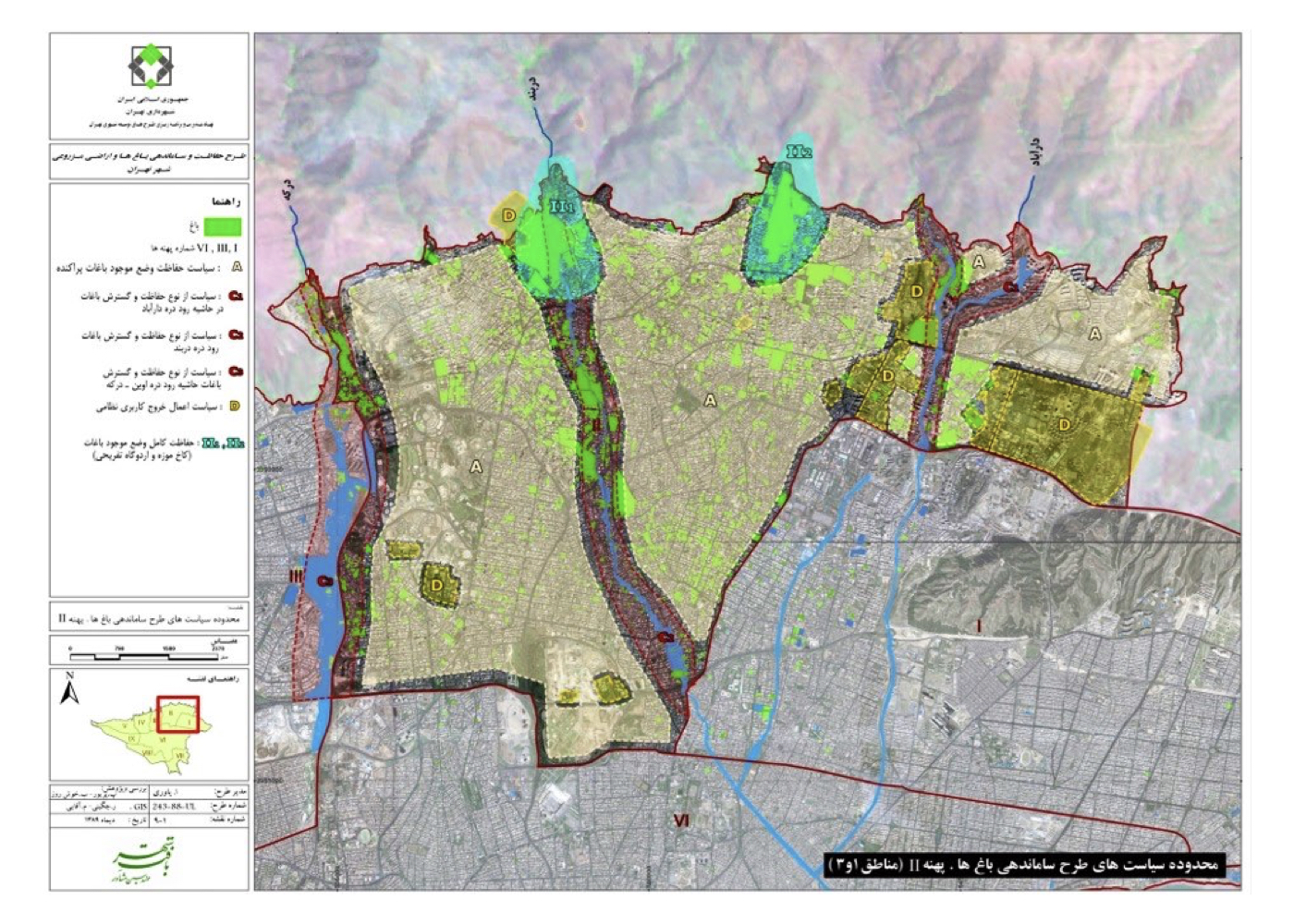

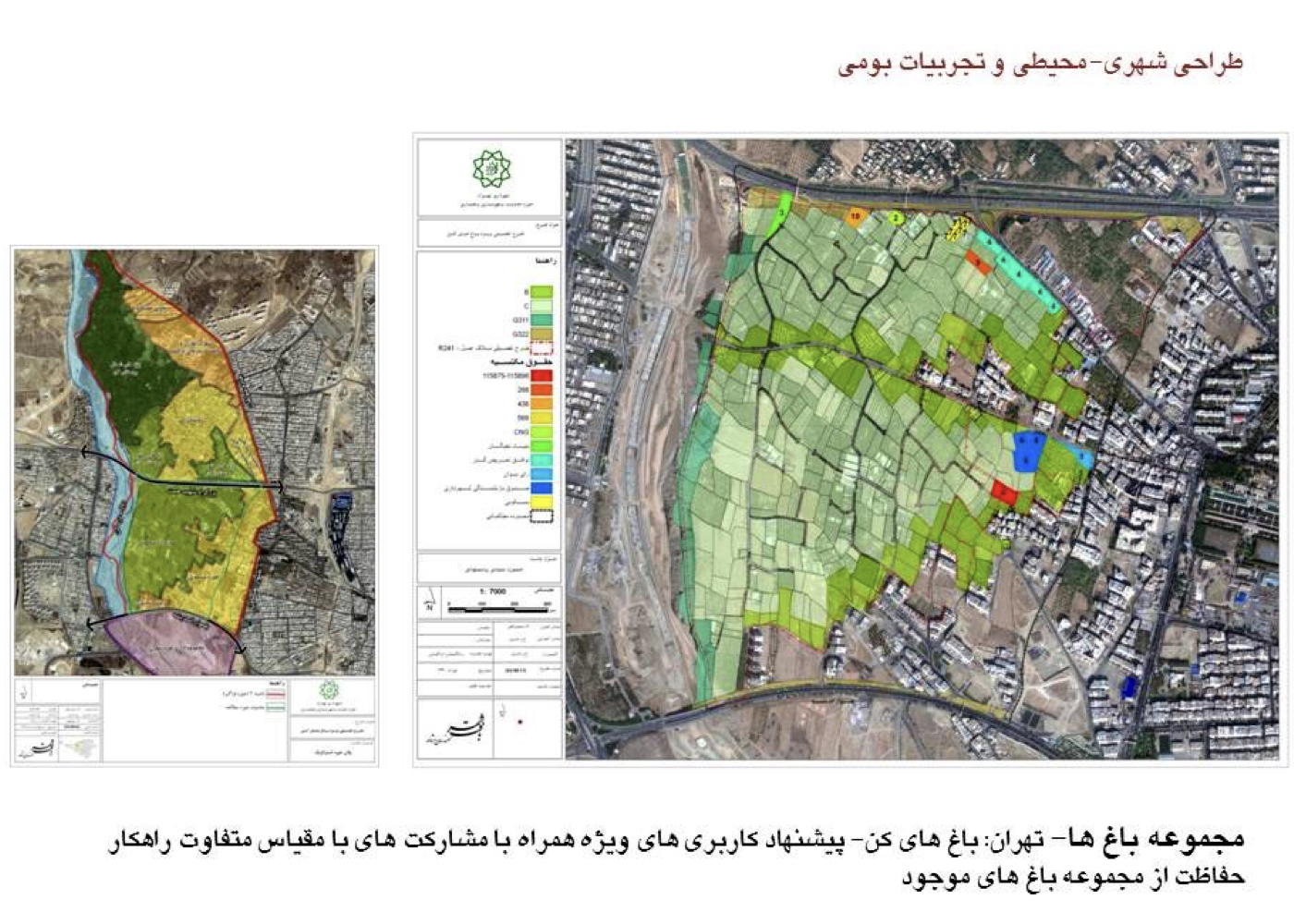

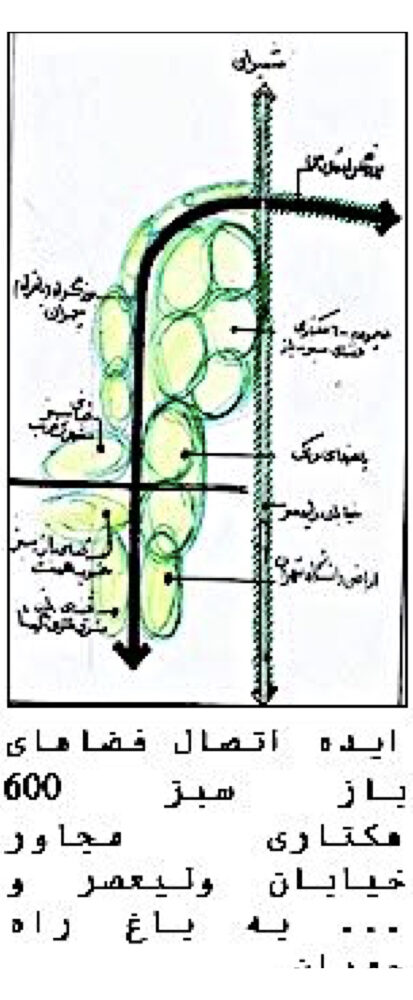

Gardens: As key cultural assets of our cities, gardens are losing their resilience due to disrupted water supply routes, destroyed qanats, pollution, and over-construction—and are now rapidly vanishing.

and…

Conclusion:

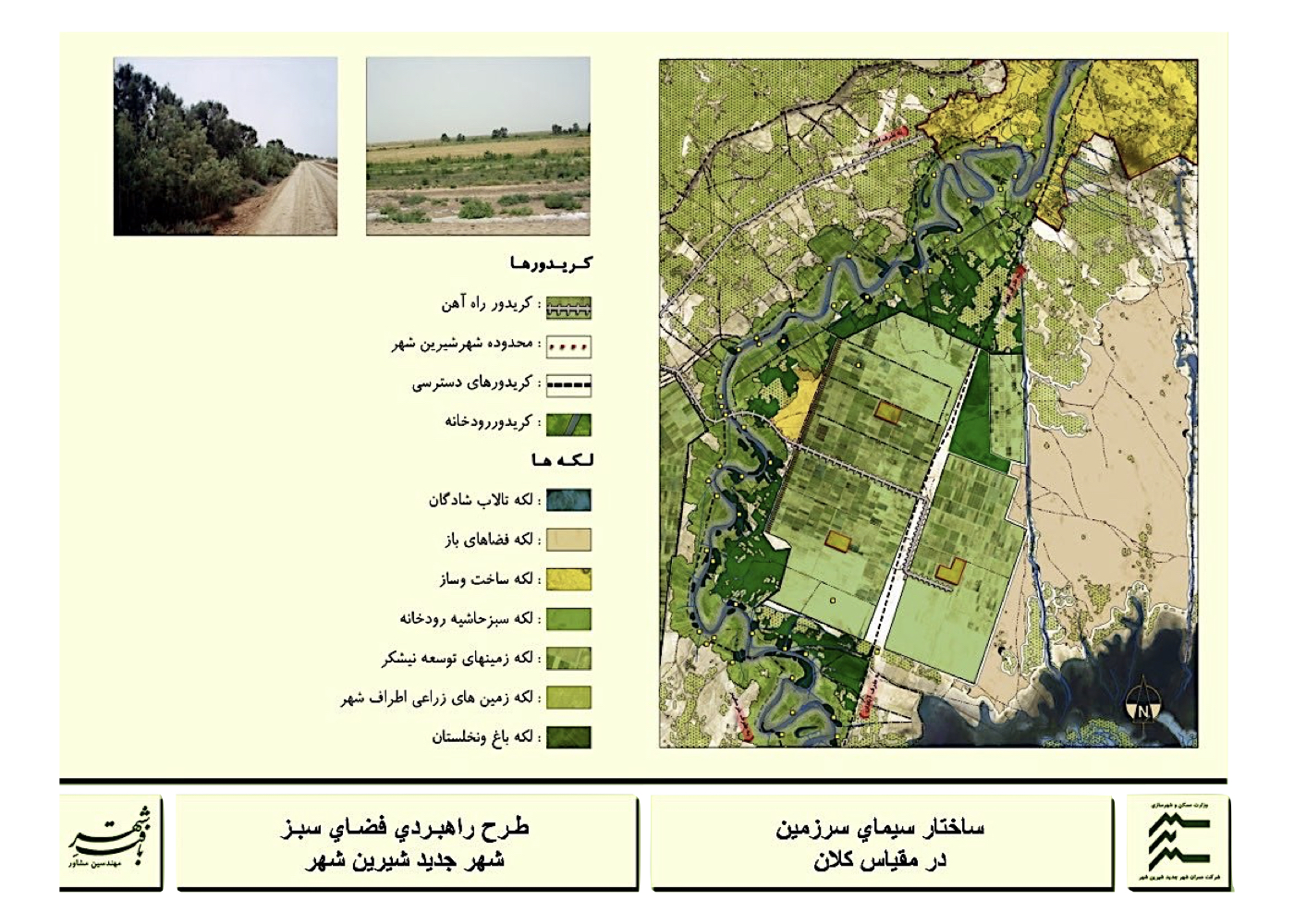

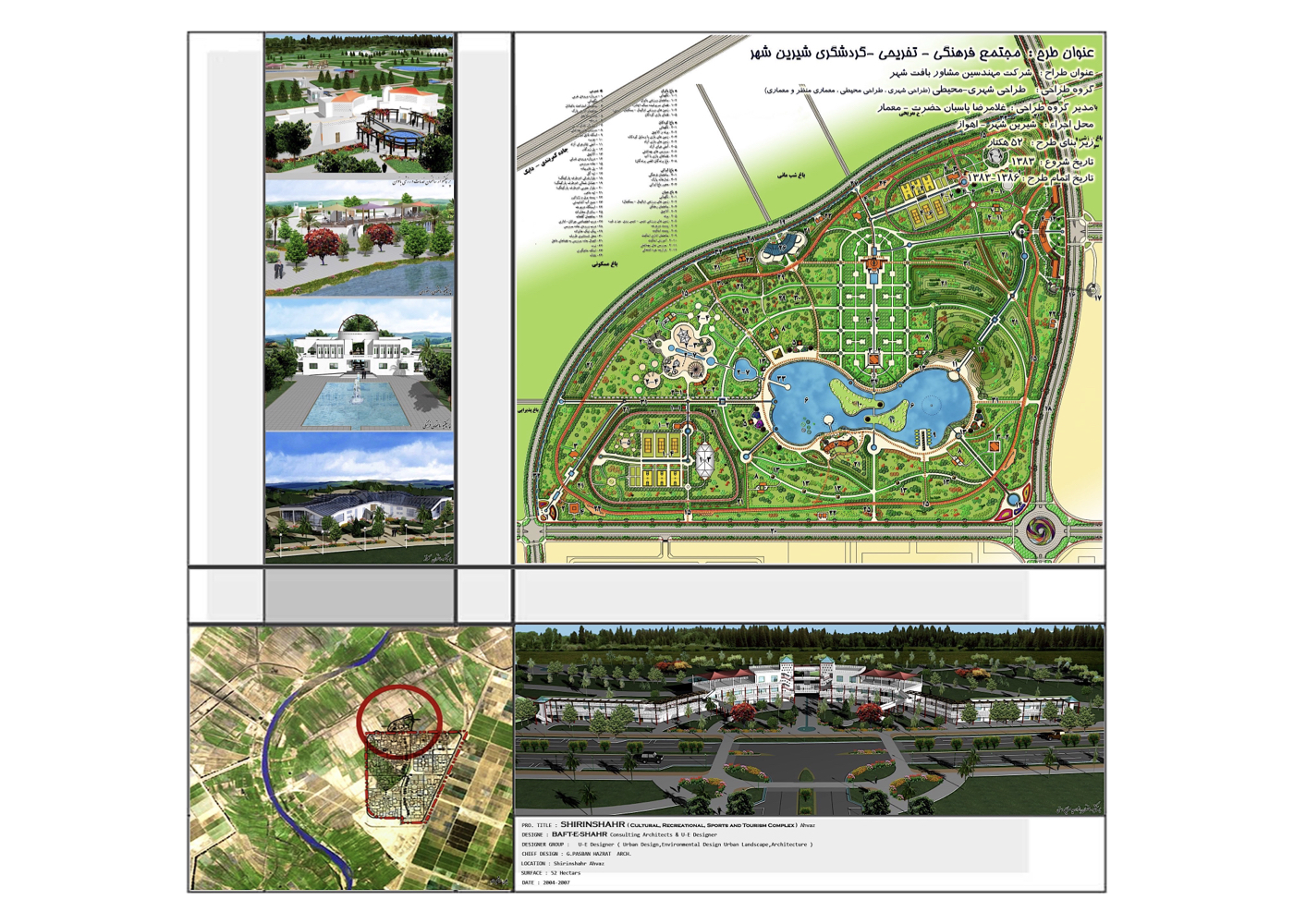

The above examples demonstrate how, after centuries of resilience, natural resources and environmental heritage are now facing destruction by our generation. In response, experts and nature advocates have worked to propose solutions to halt this destructive trajectory and restore balance. In this spirit, I have—alongside fellow committed colleagues and drawing on experience with nature-based projects—proposed the theory of Urban–Environmental Design. A theory that, by interrupting the current course of degradation, enables responsible use of natural treasures and supports sustainable development of our cities and country. It is hoped that this effort will play a positive role in achieving its intended goals.

Definition of Urban–Environmental Design:

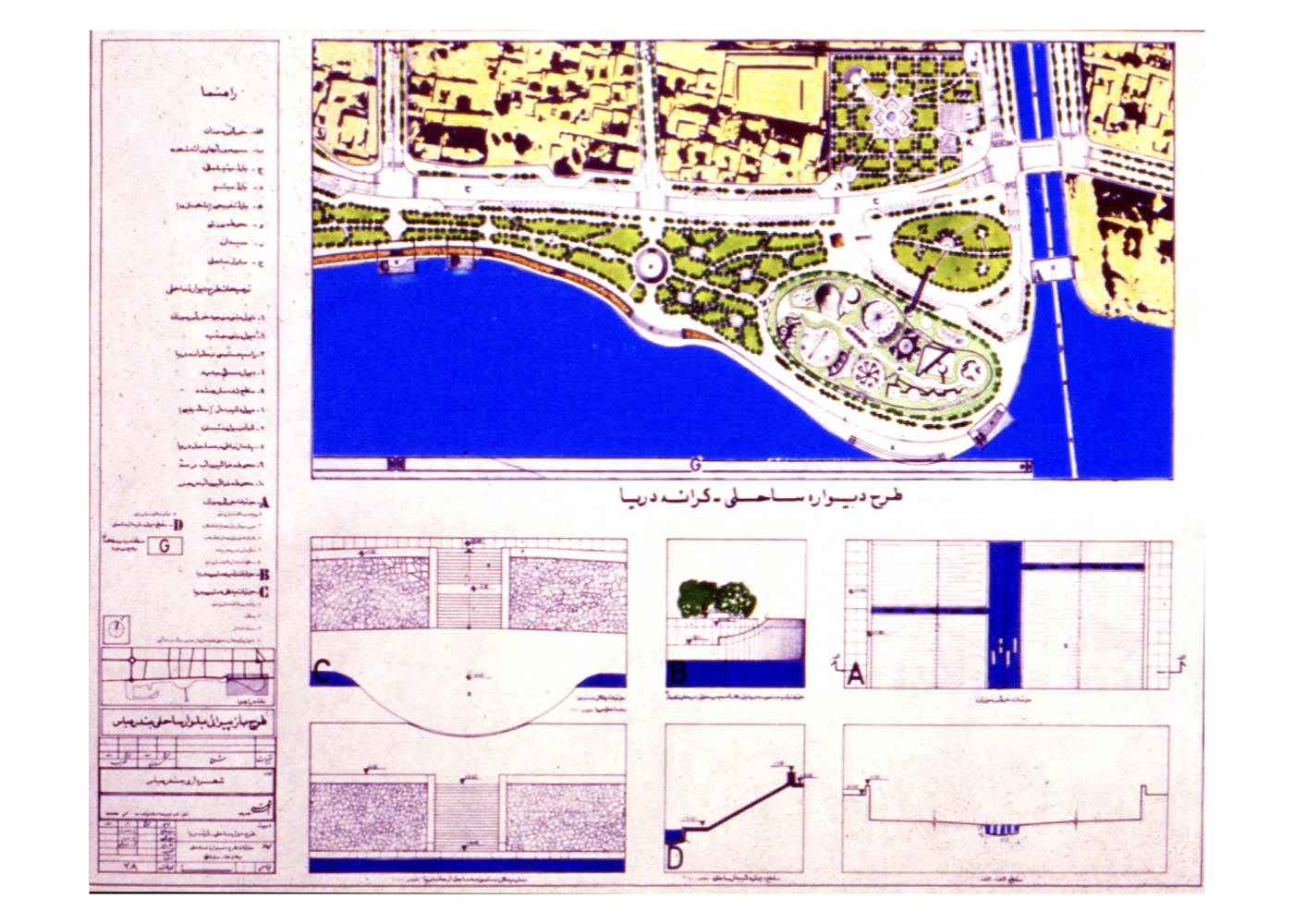

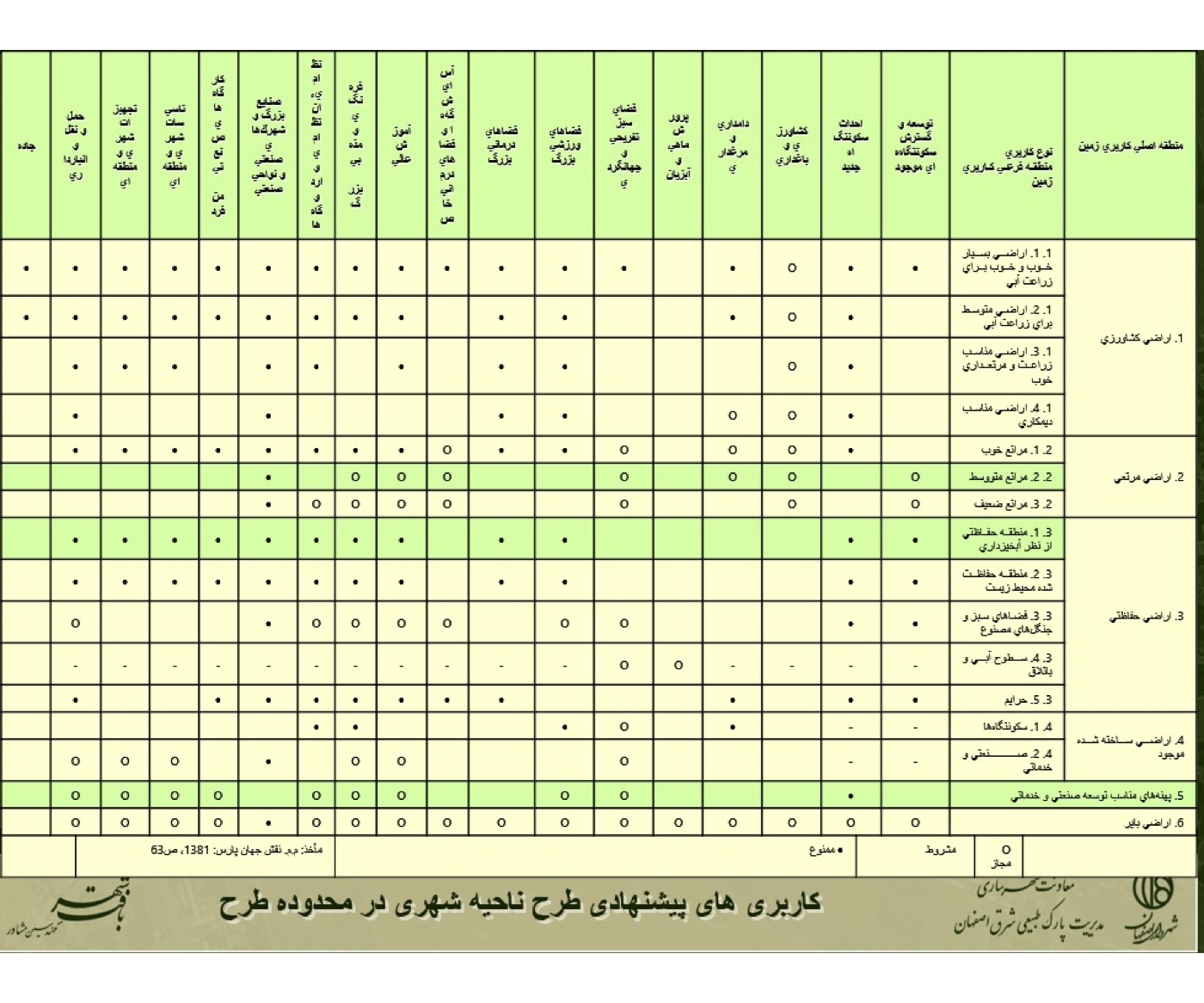

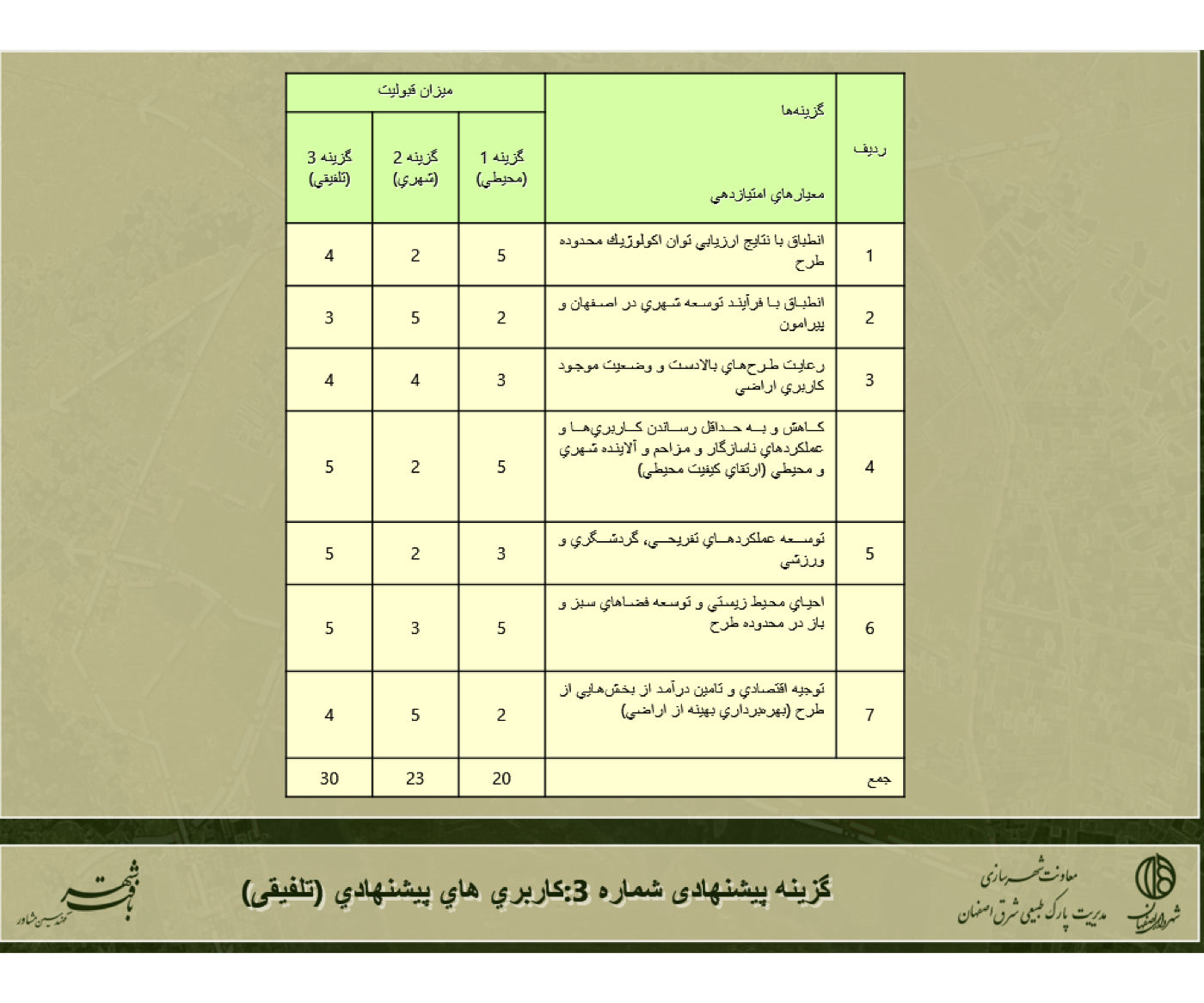

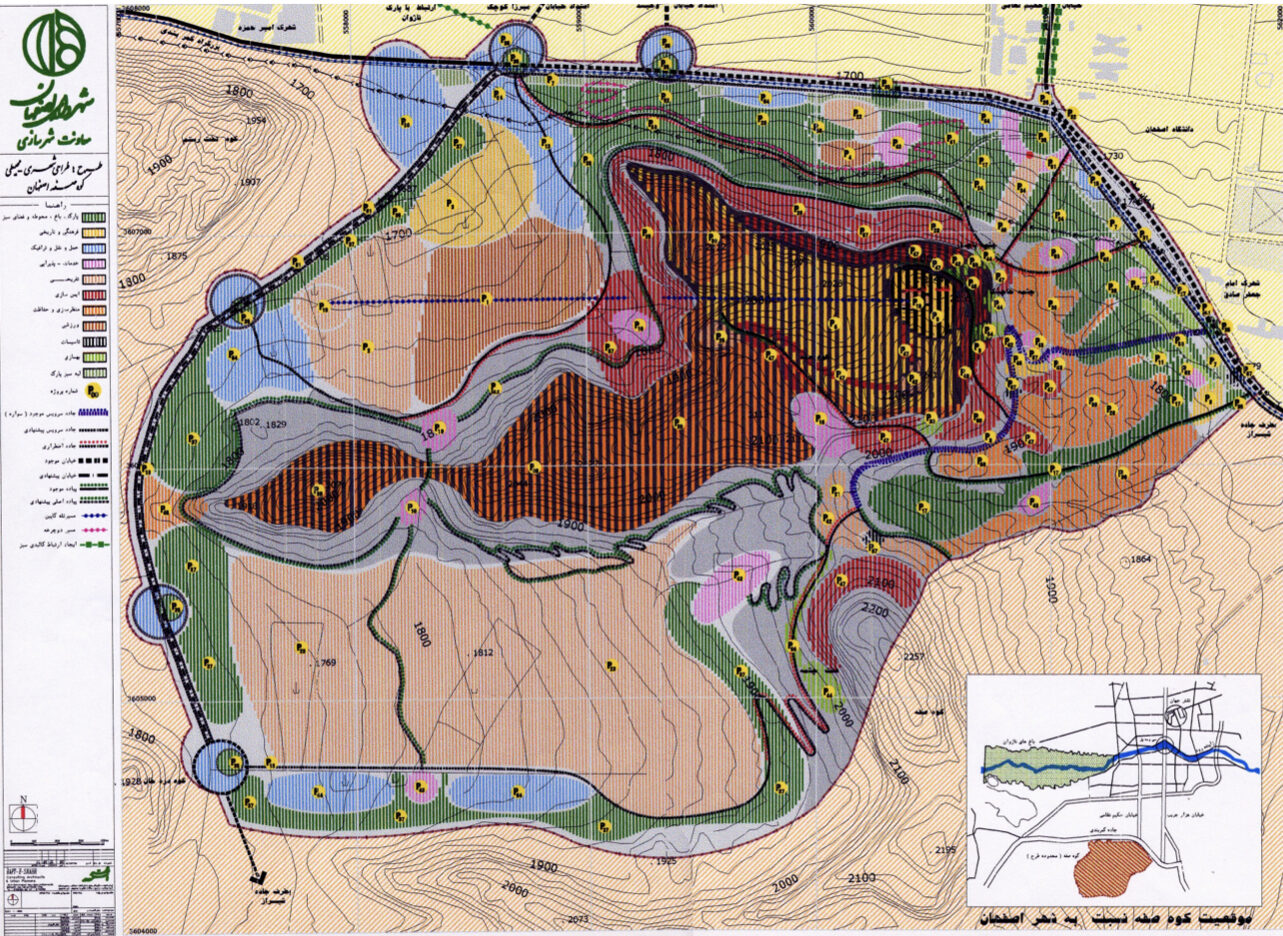

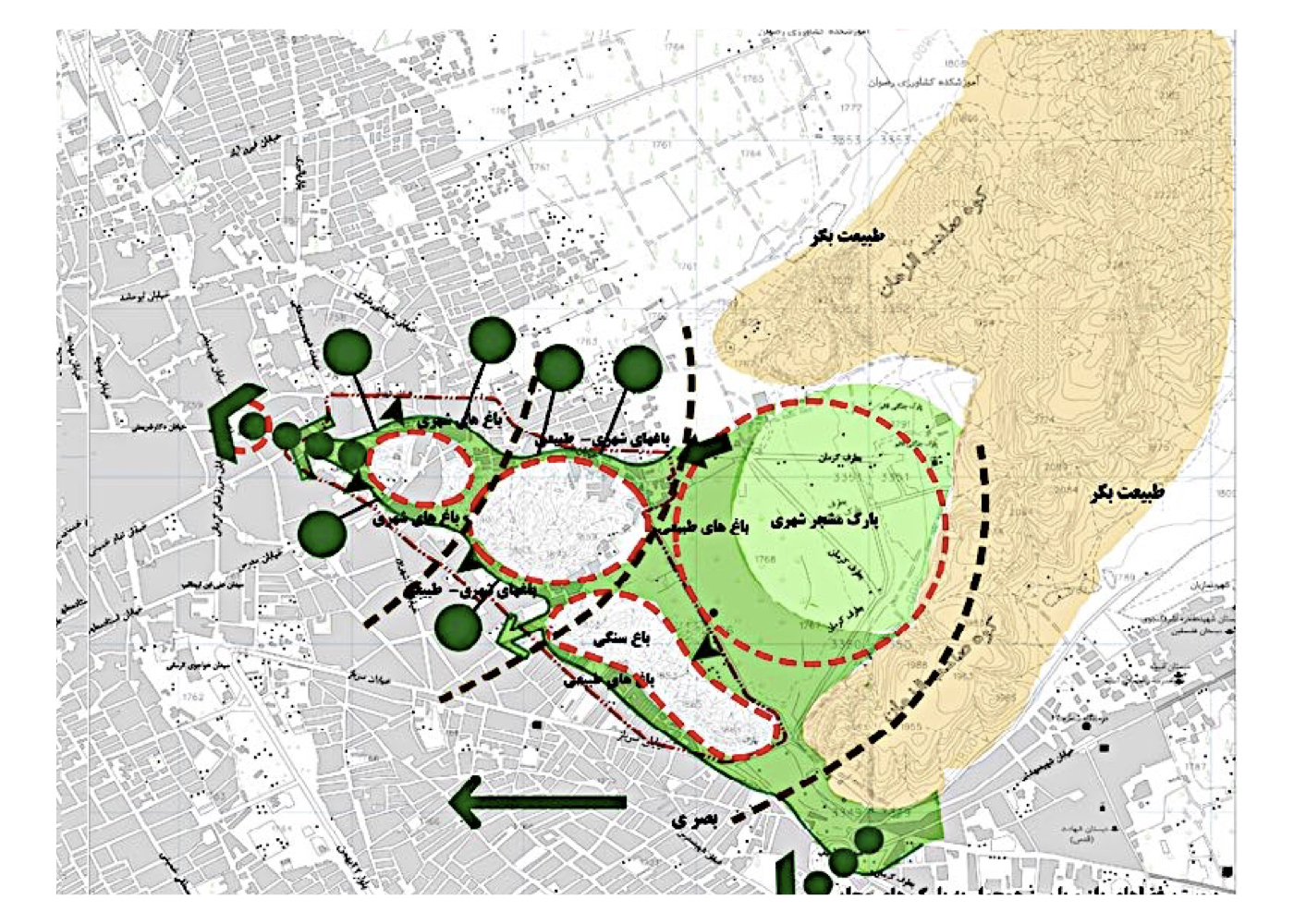

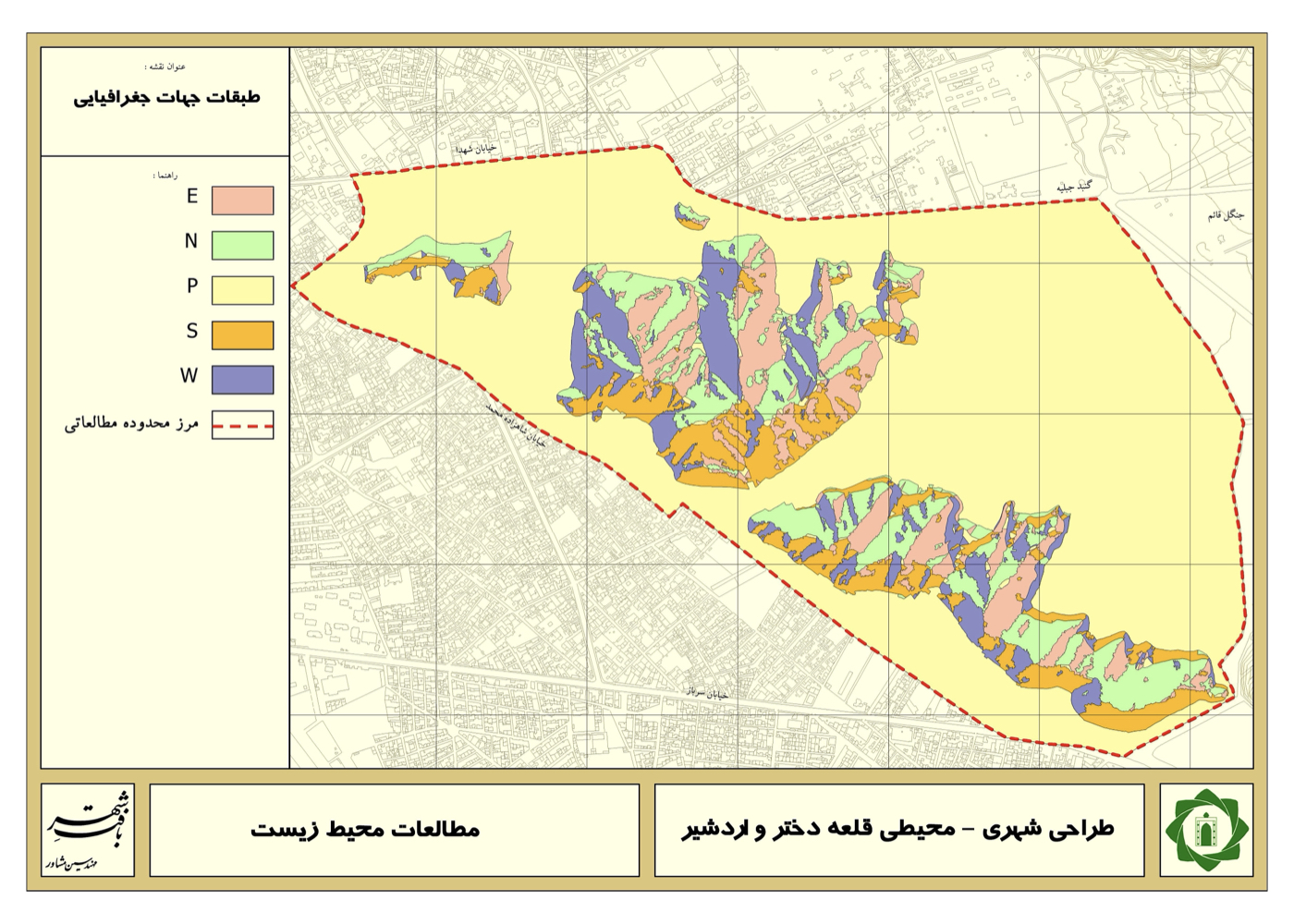

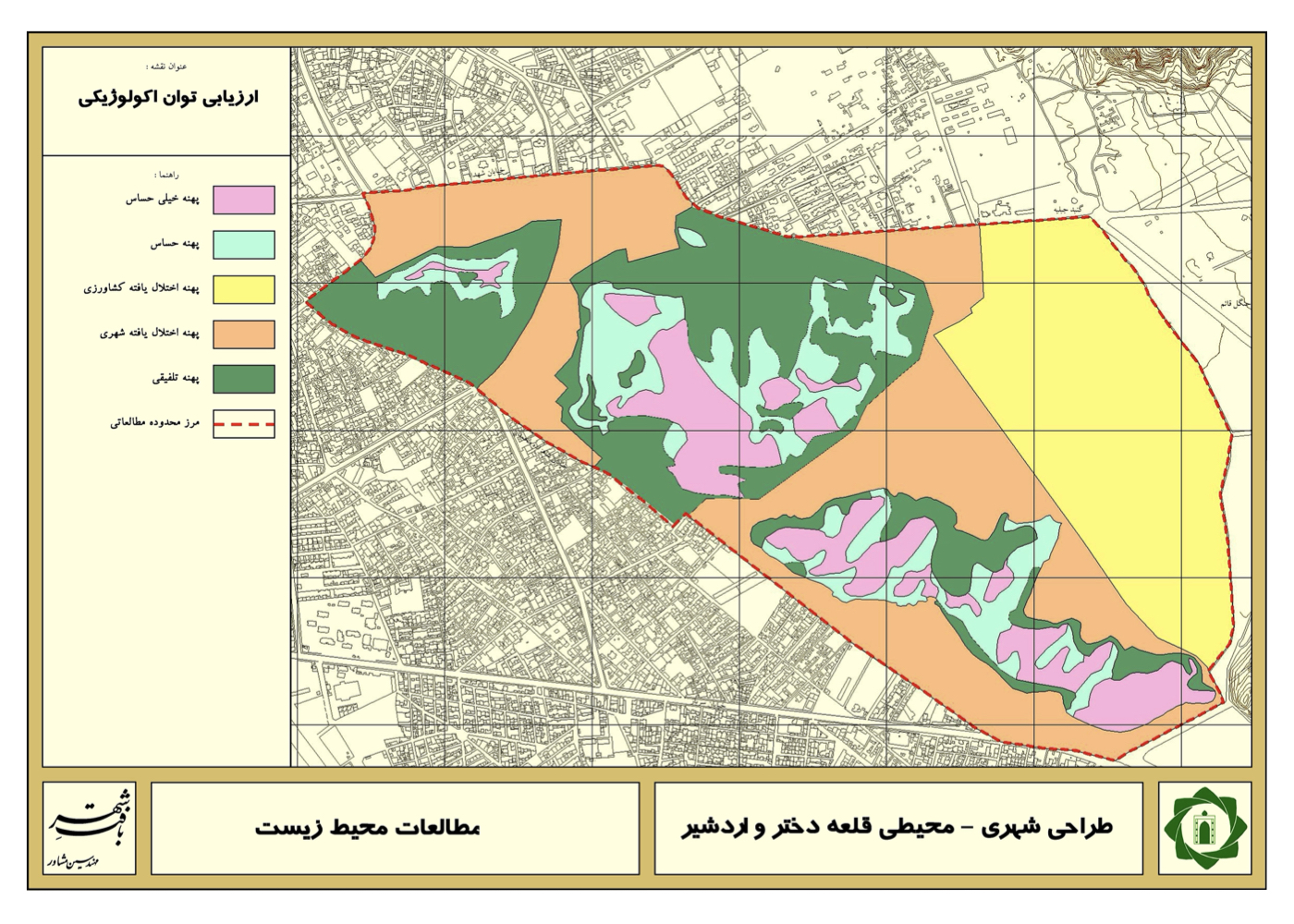

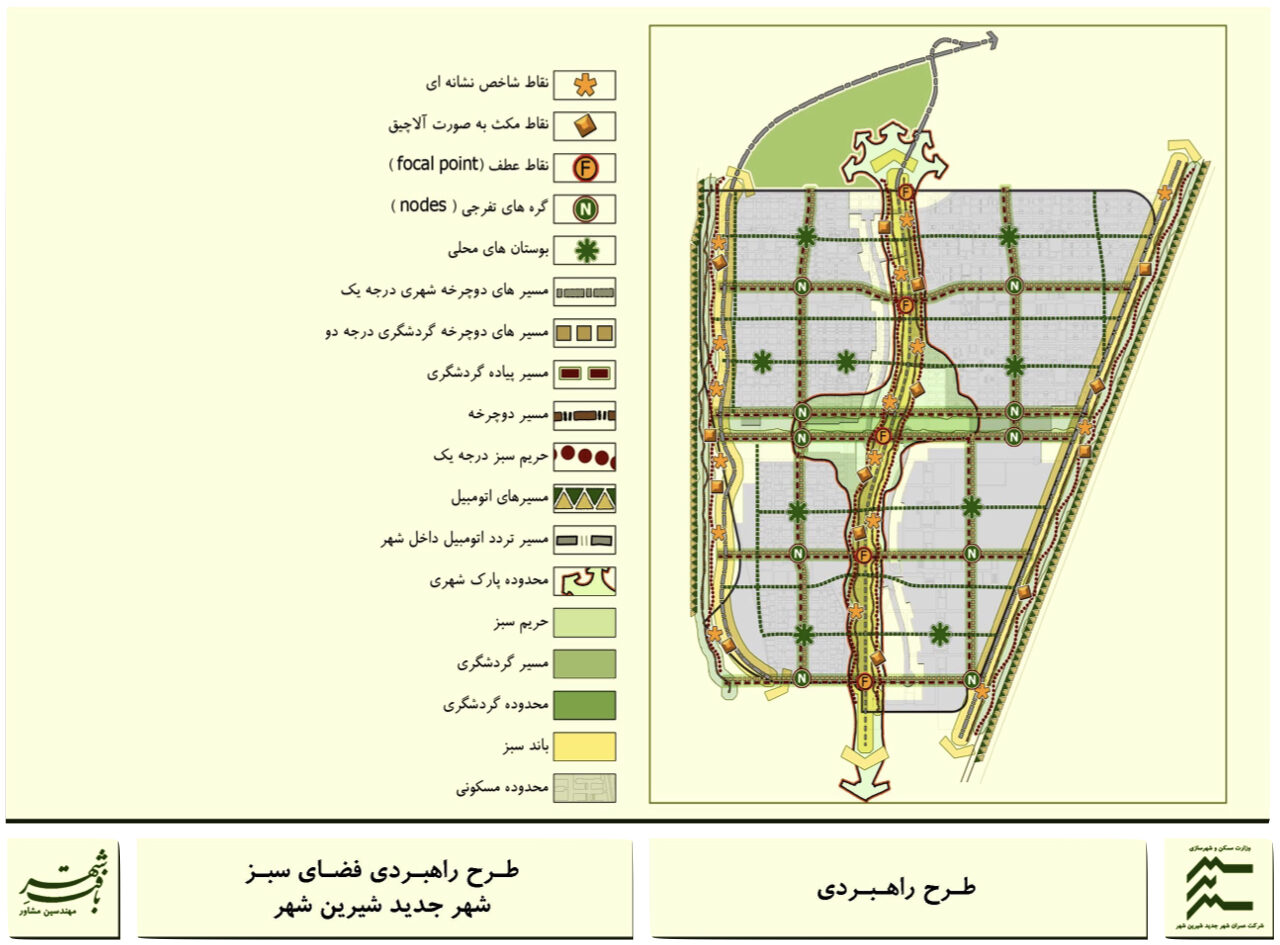

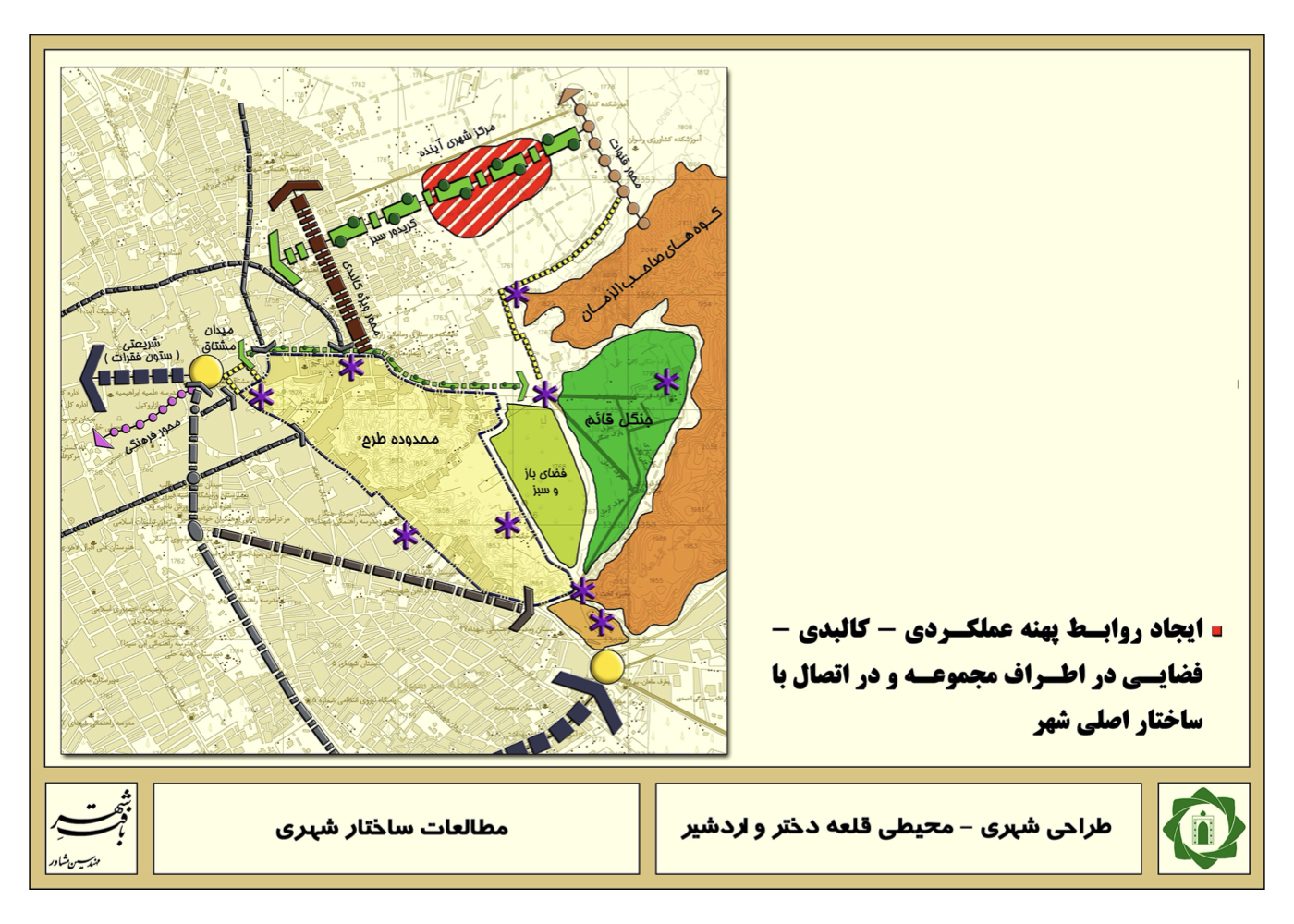

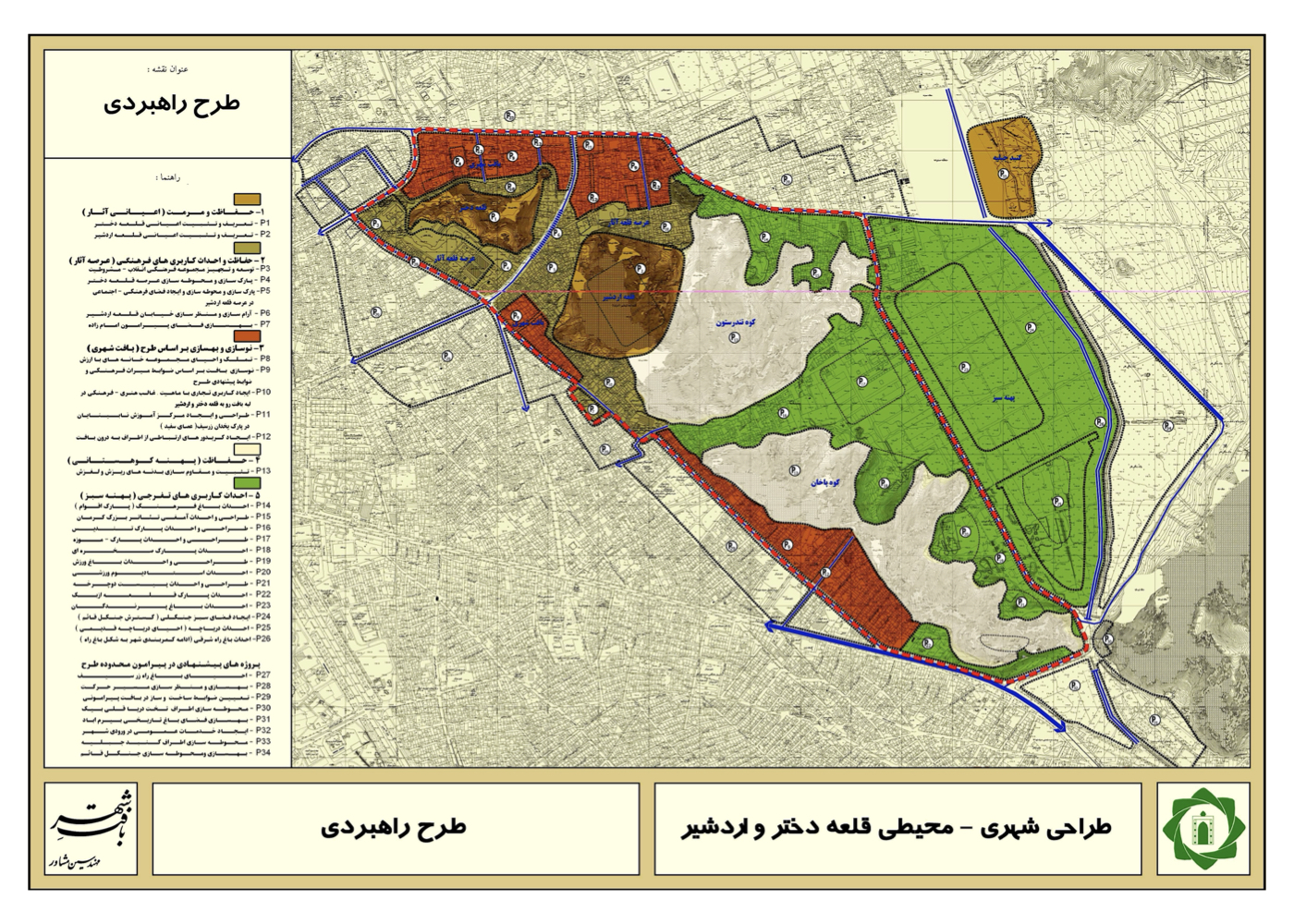

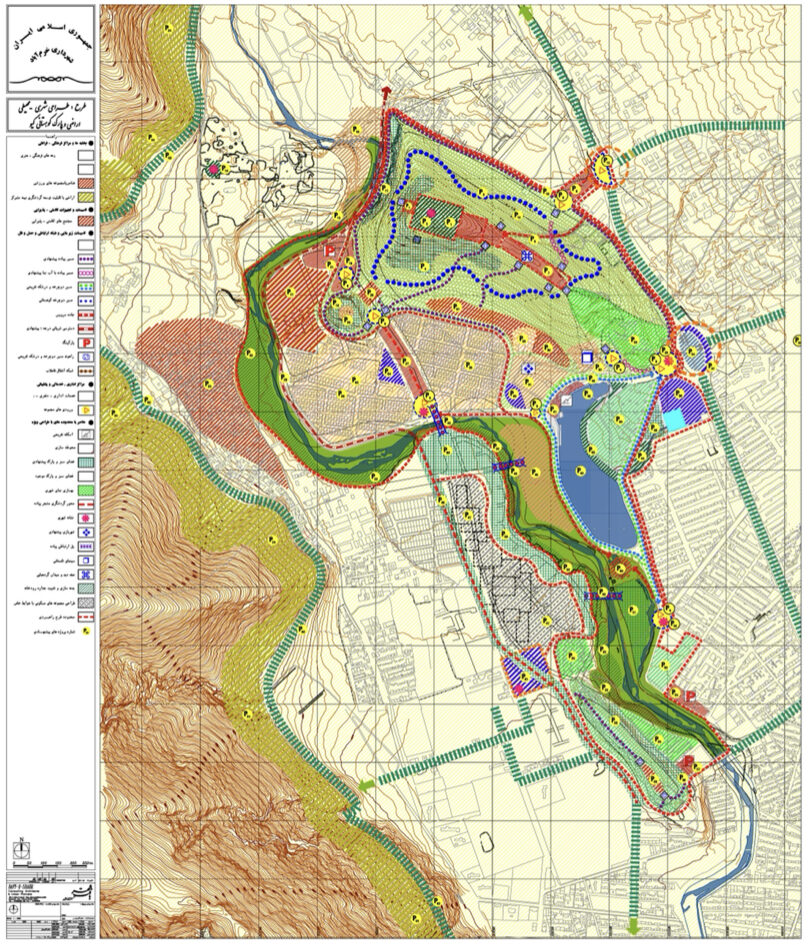

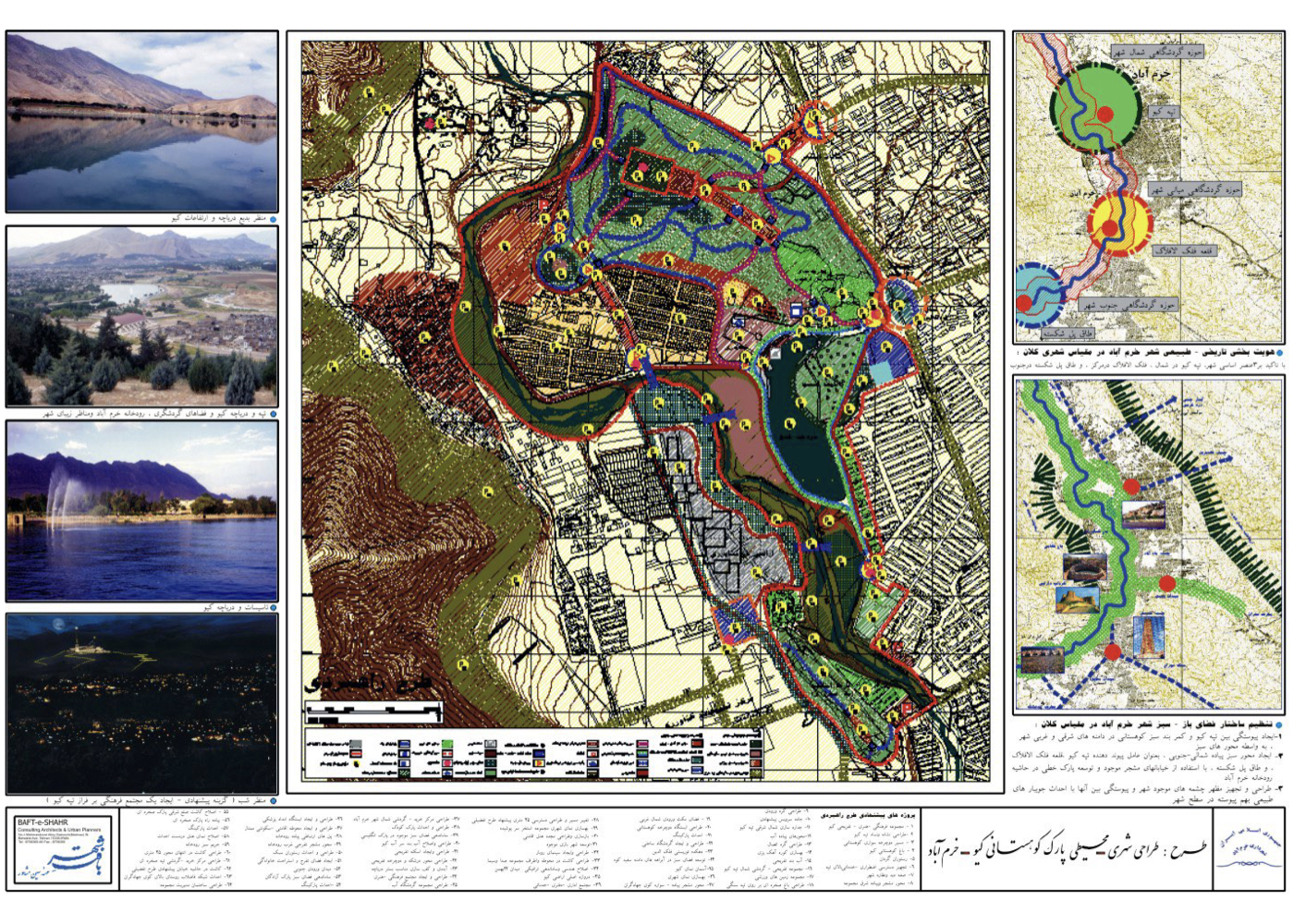

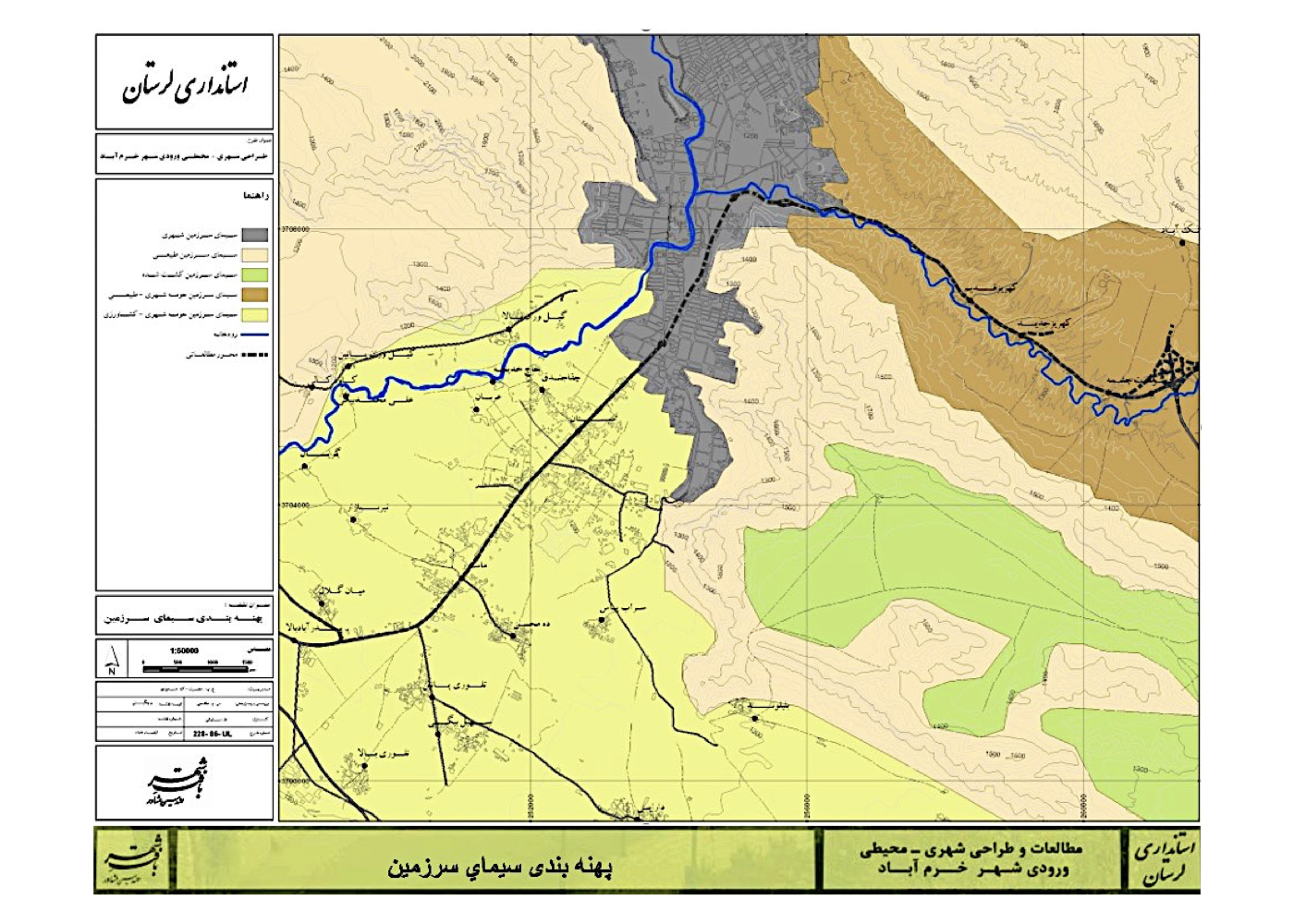

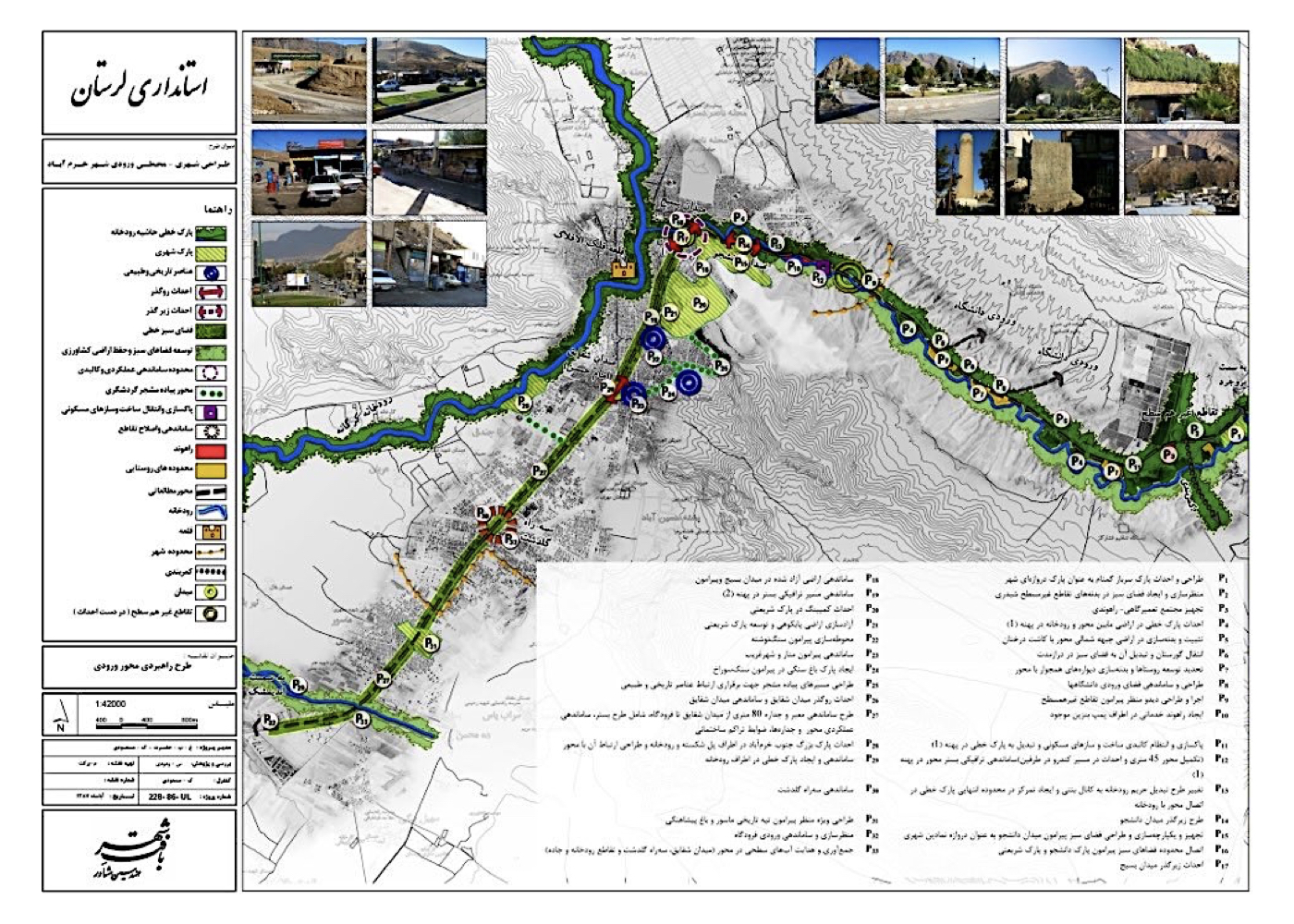

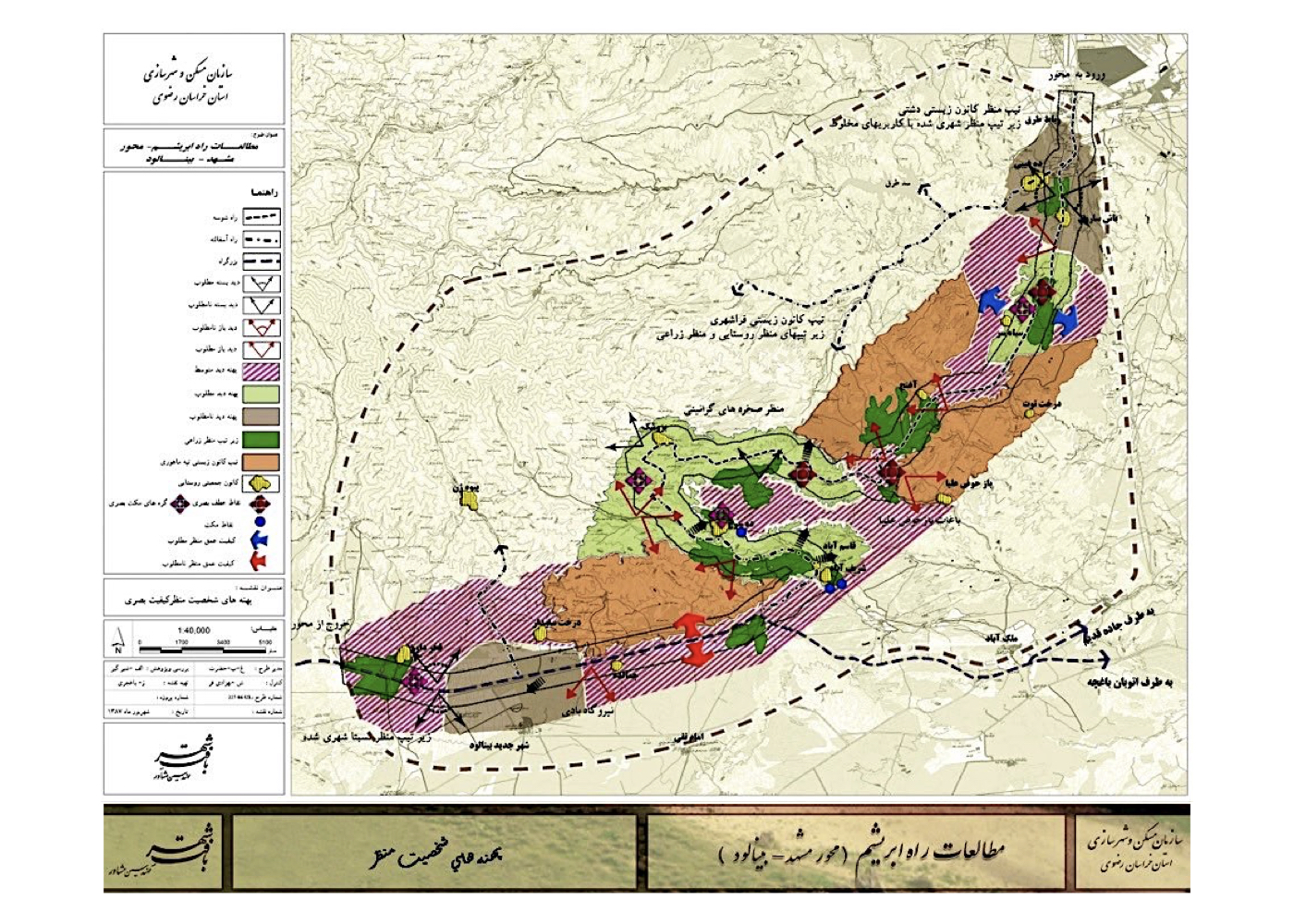

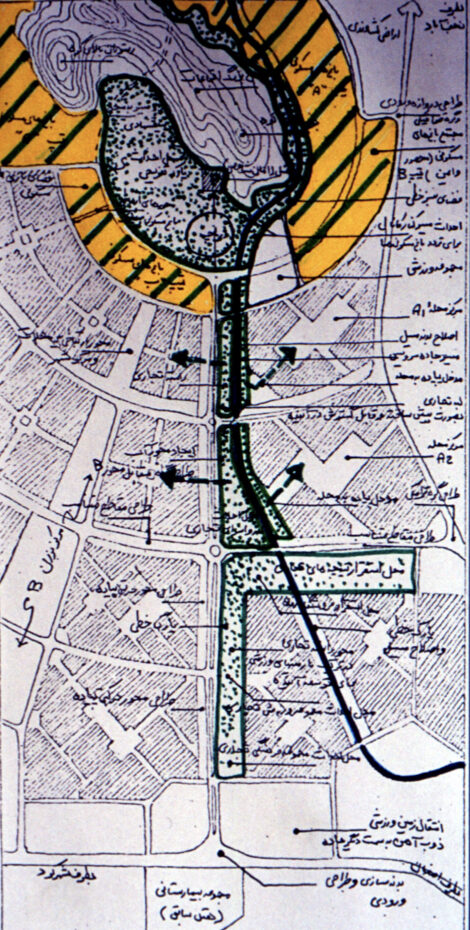

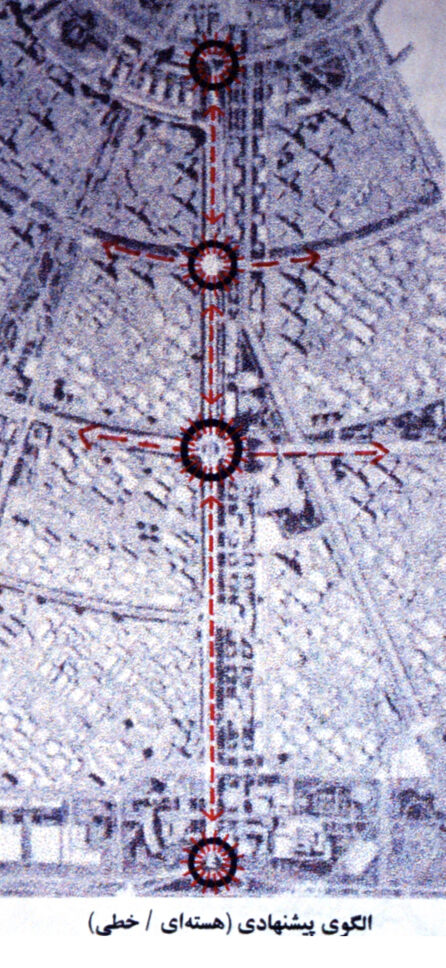

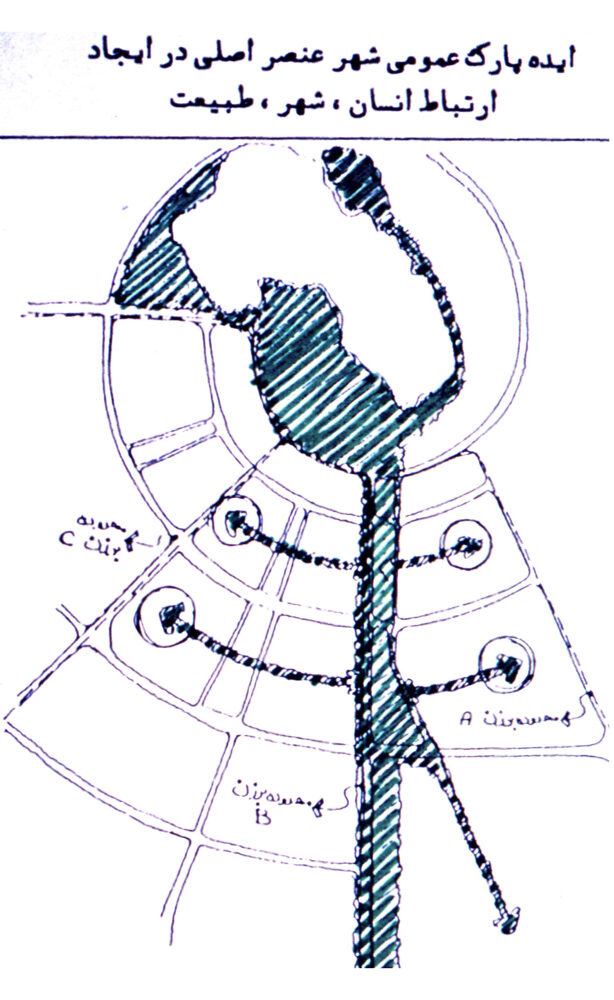

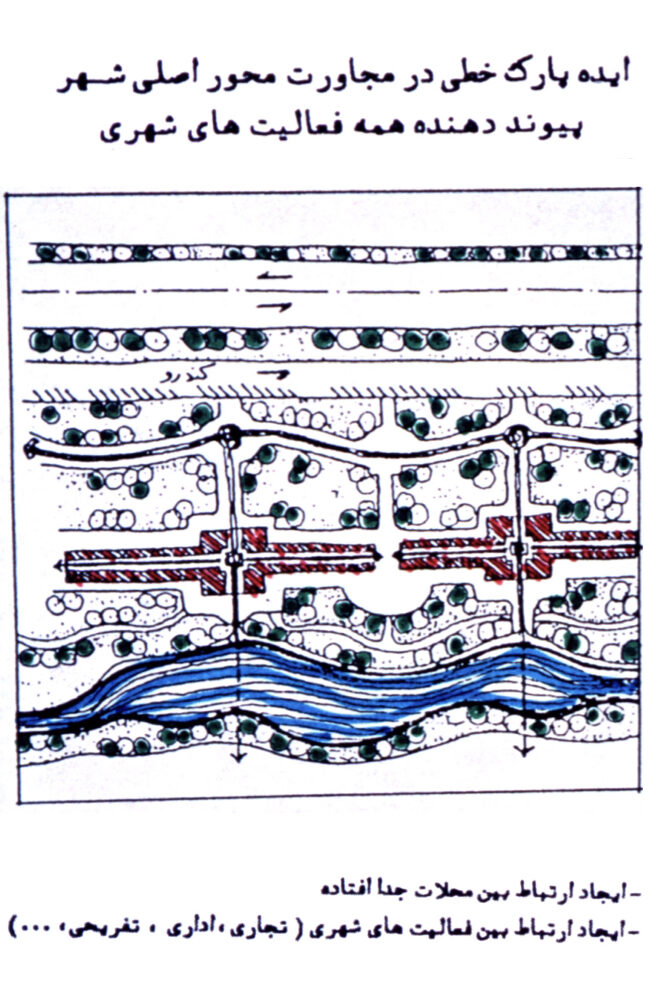

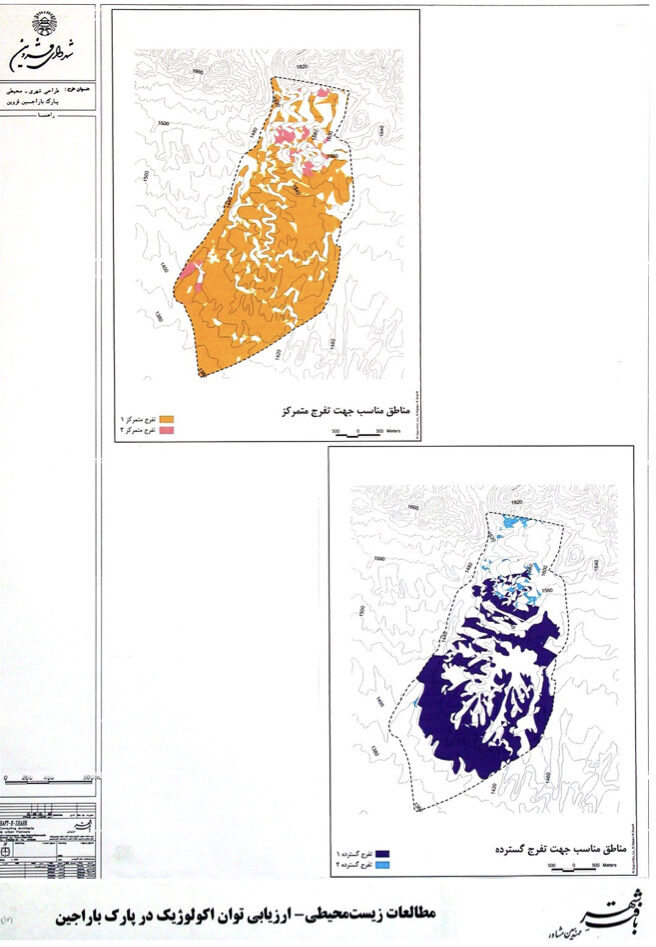

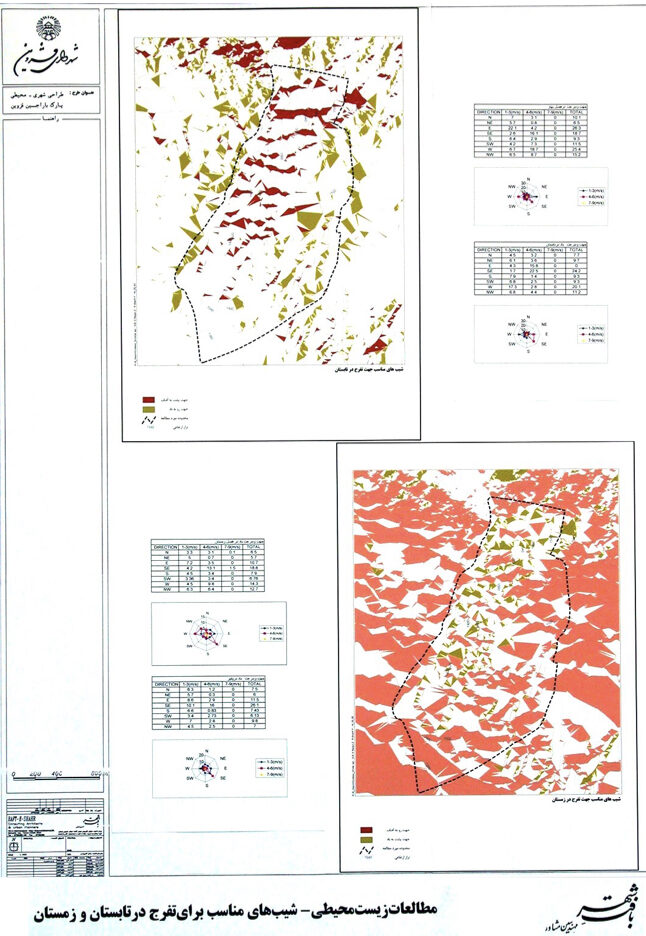

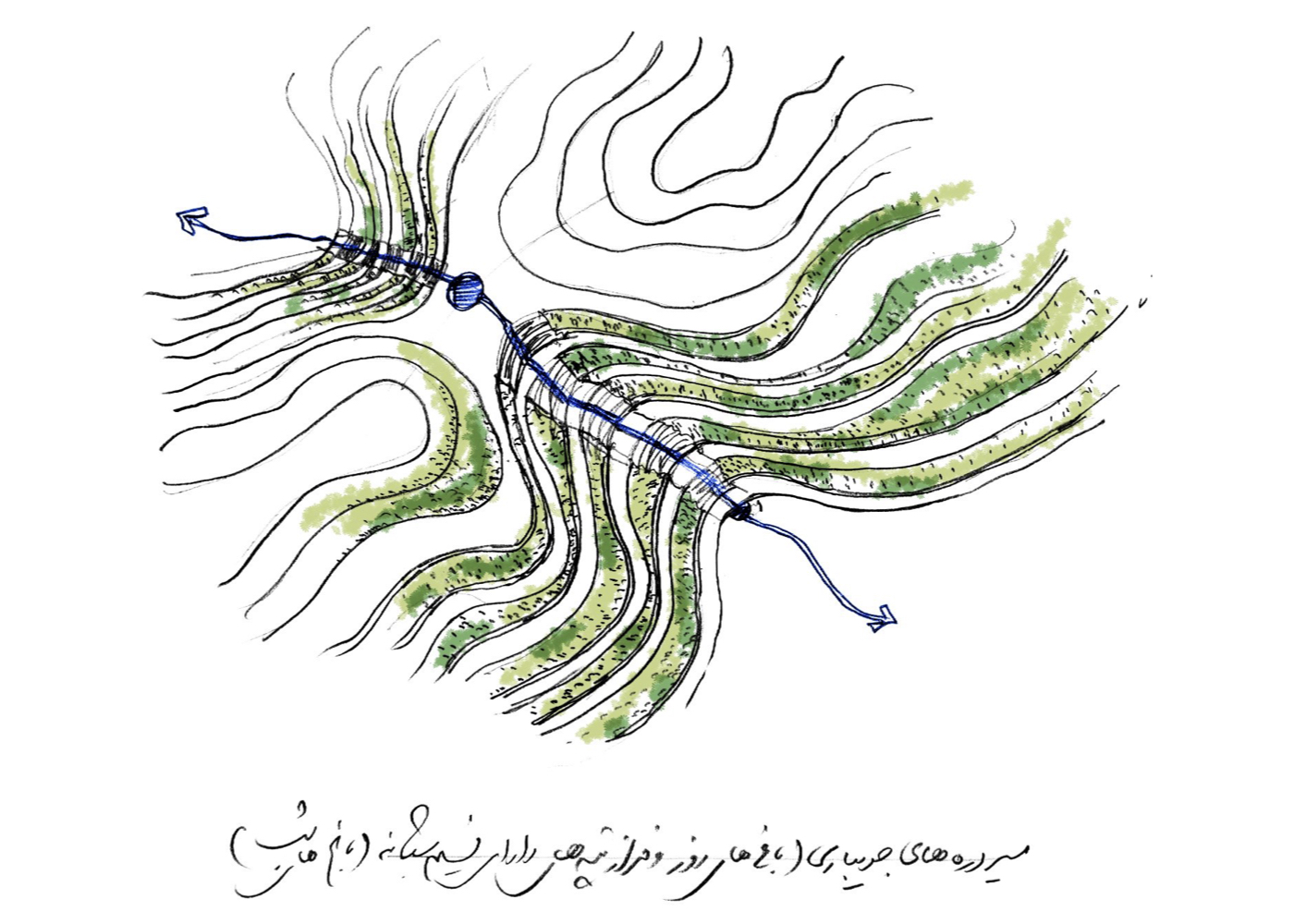

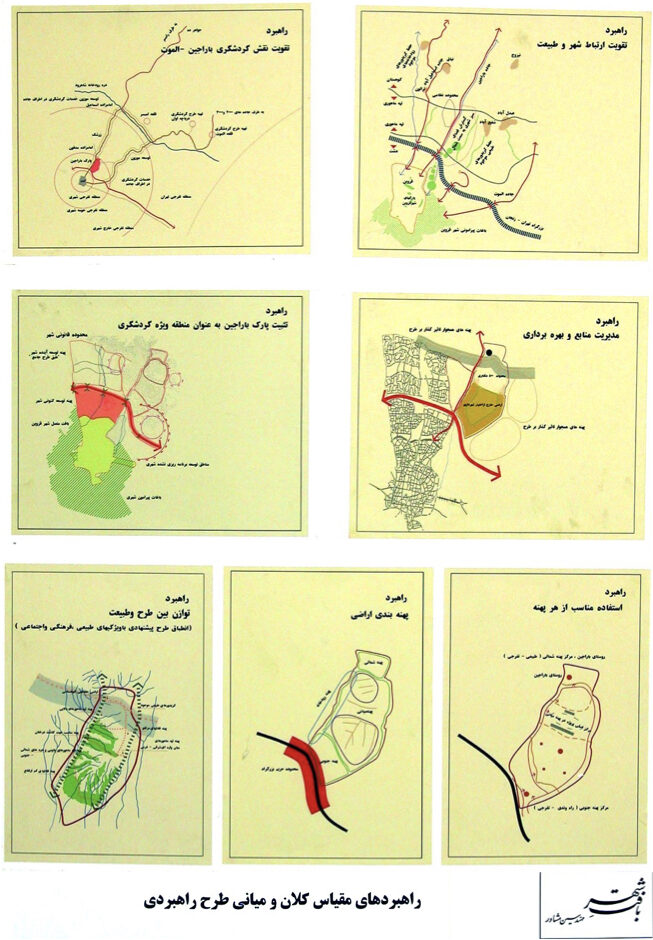

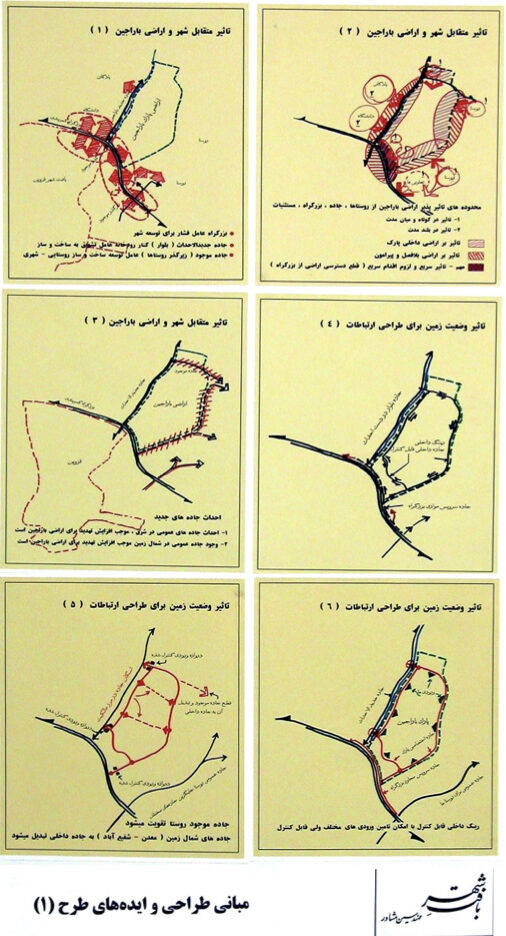

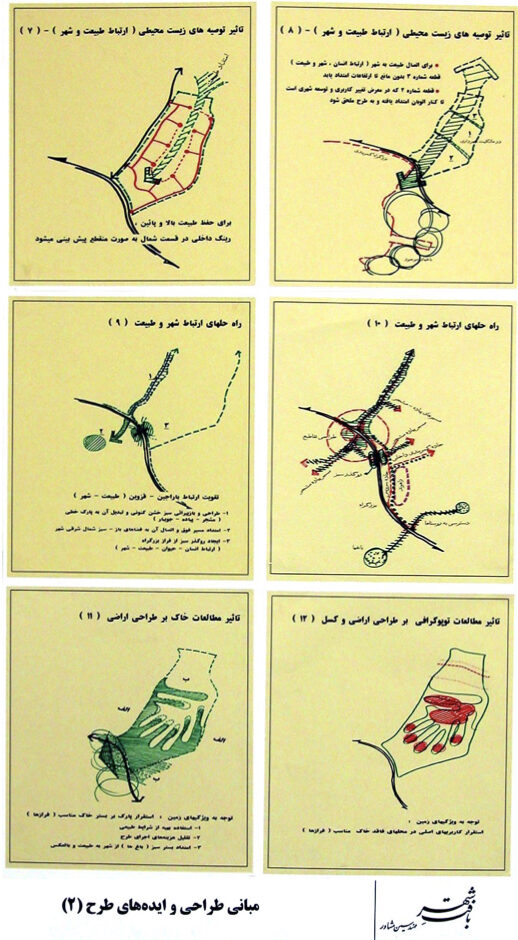

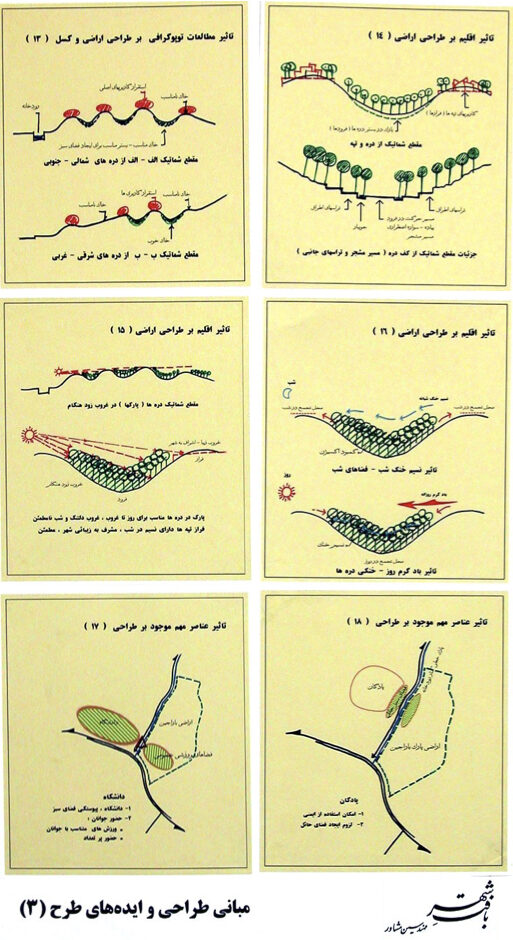

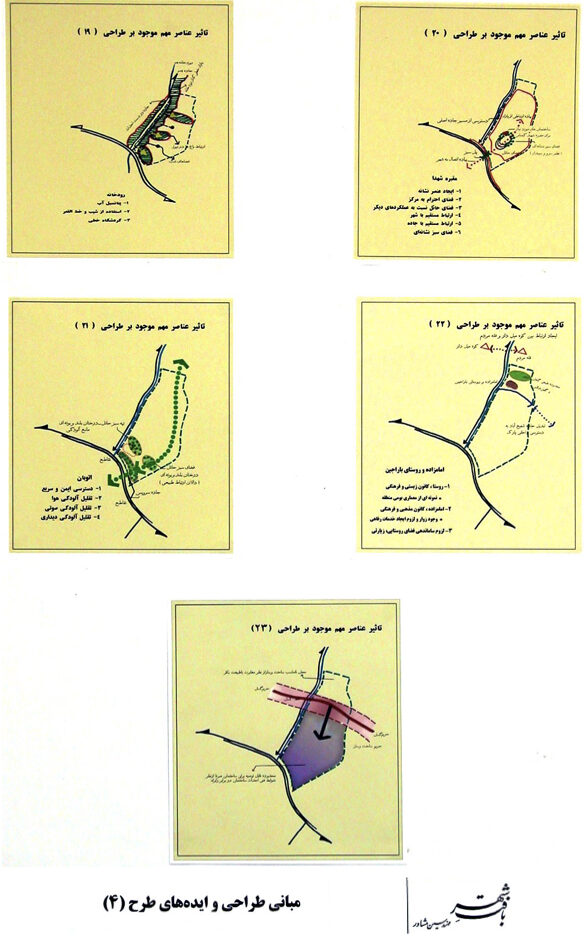

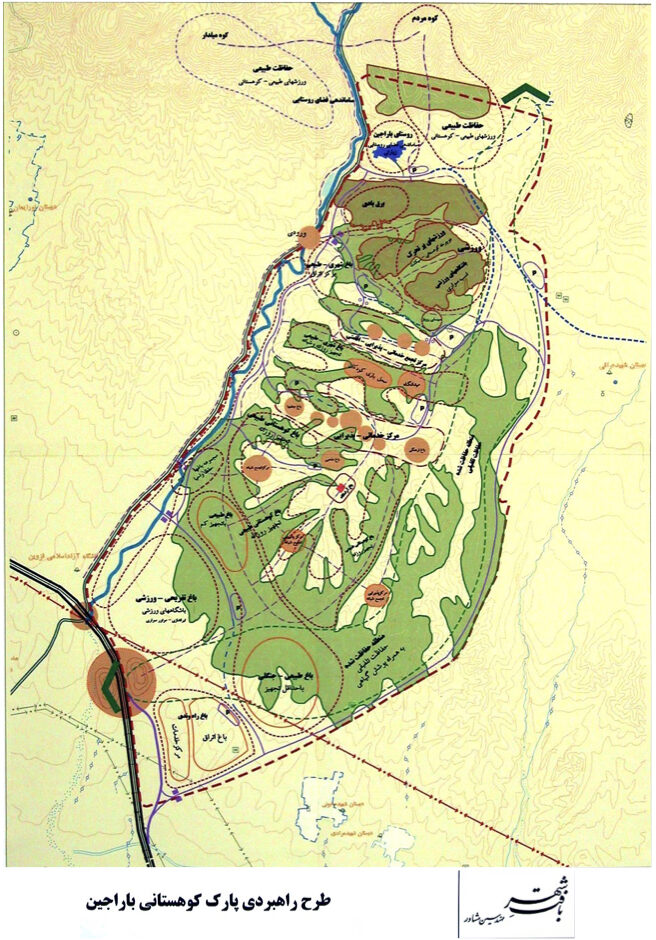

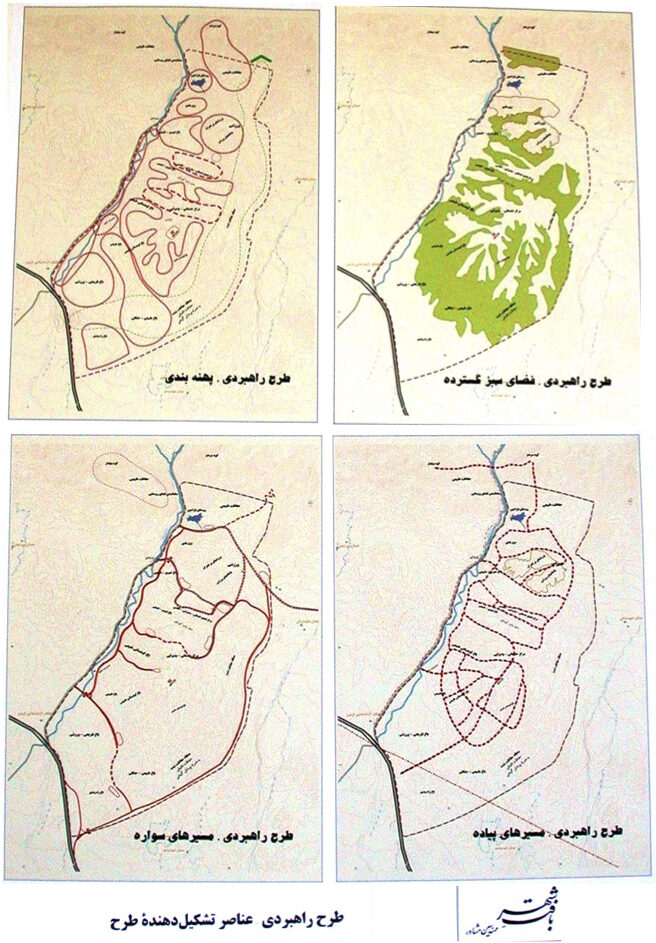

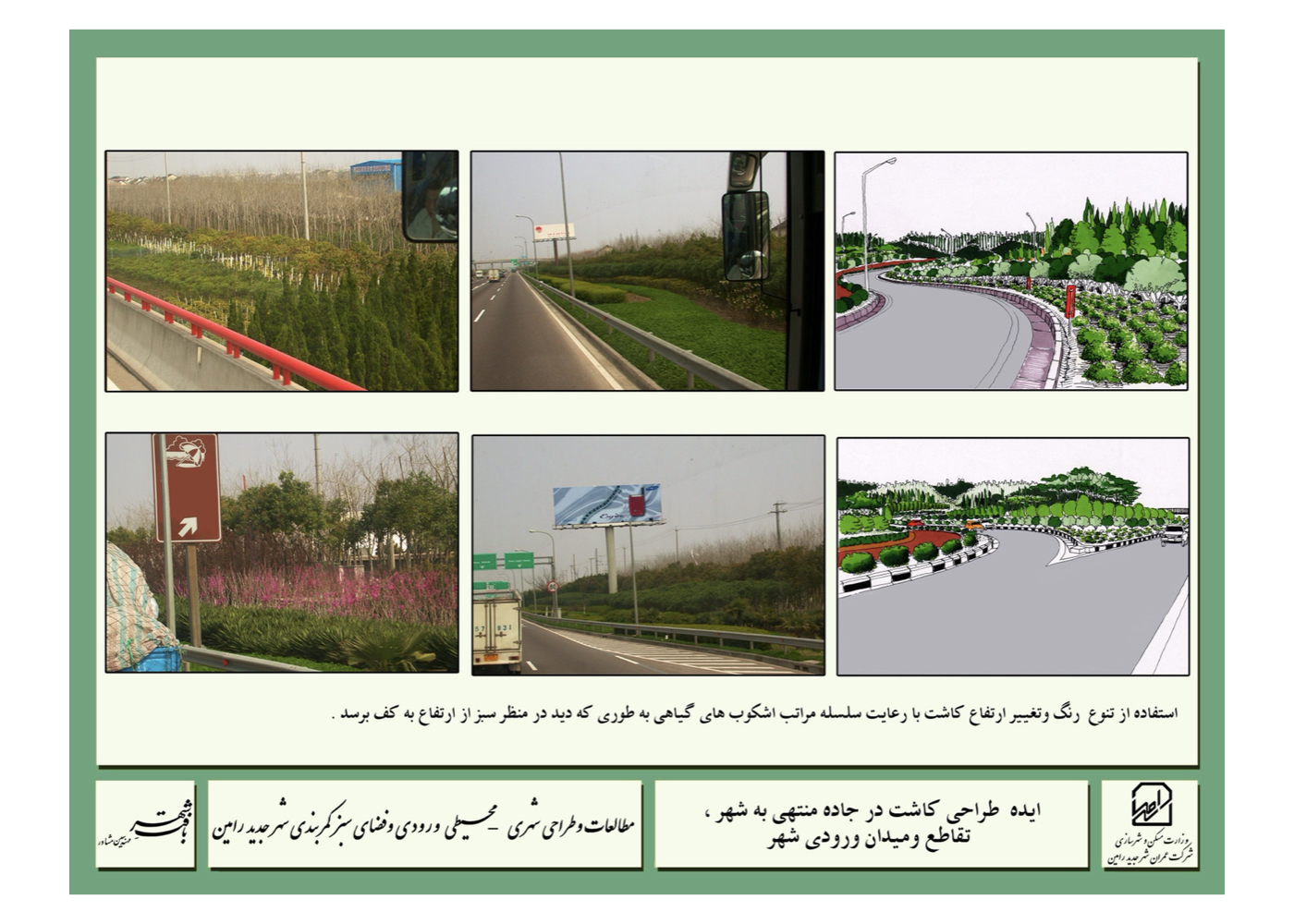

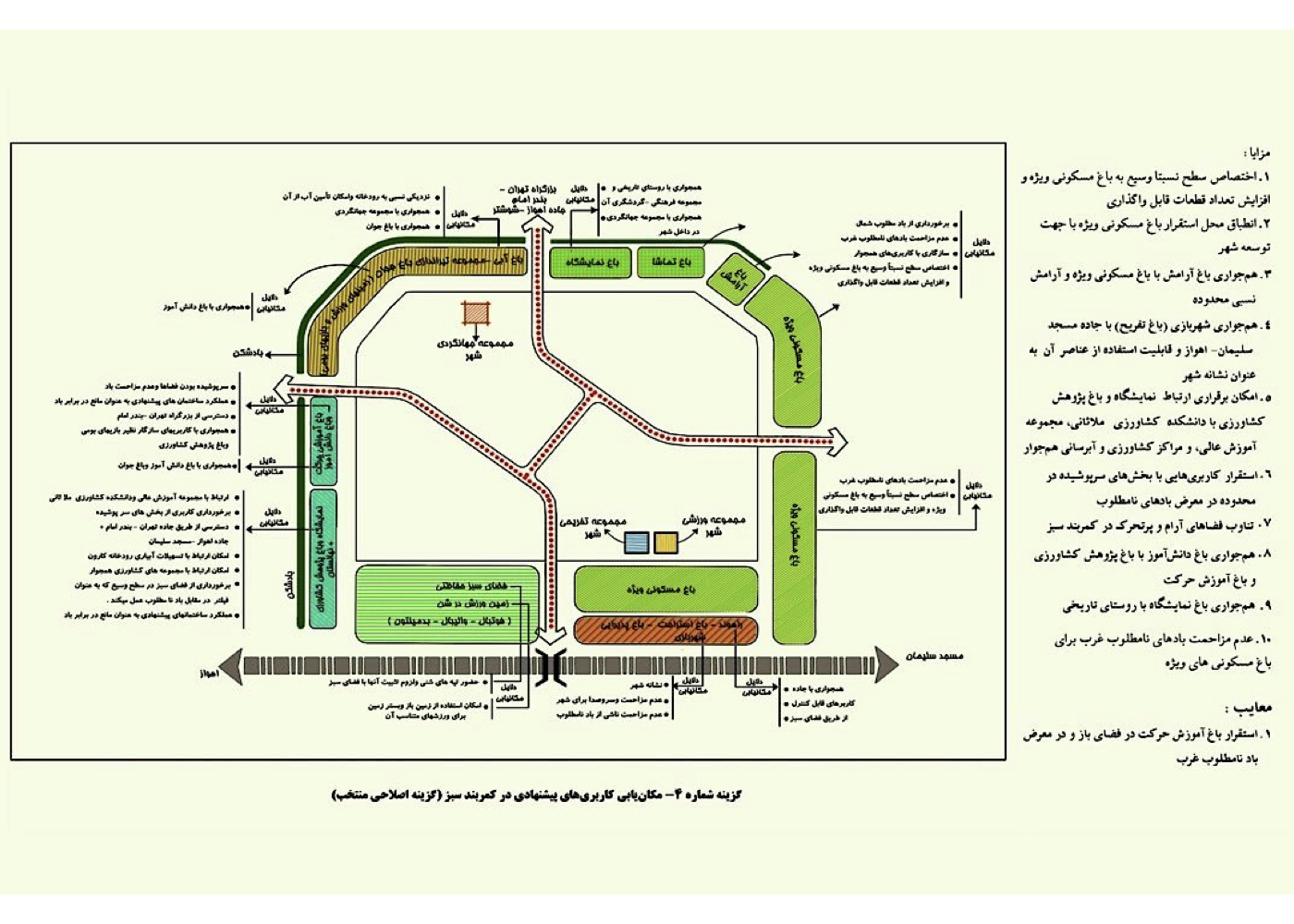

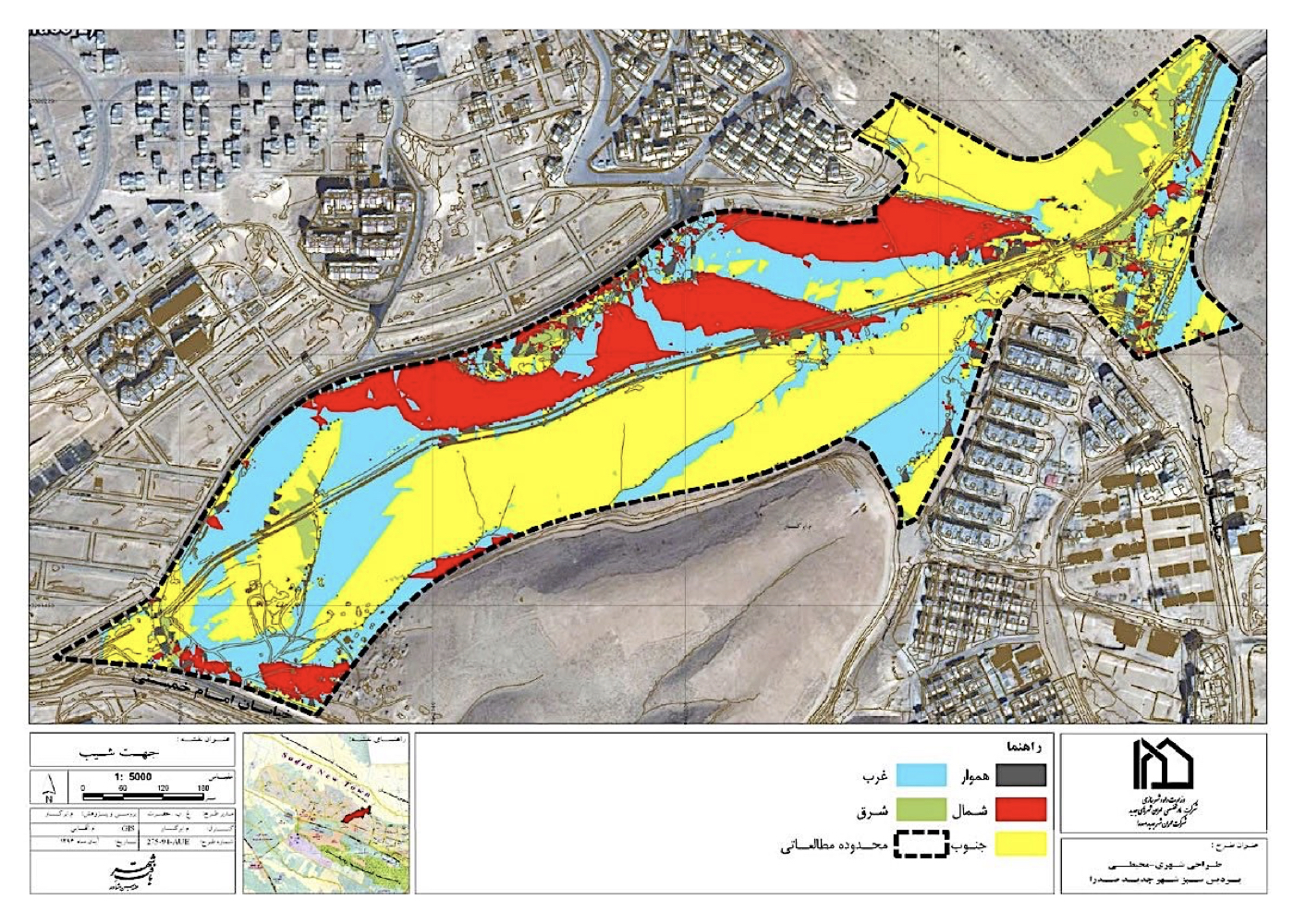

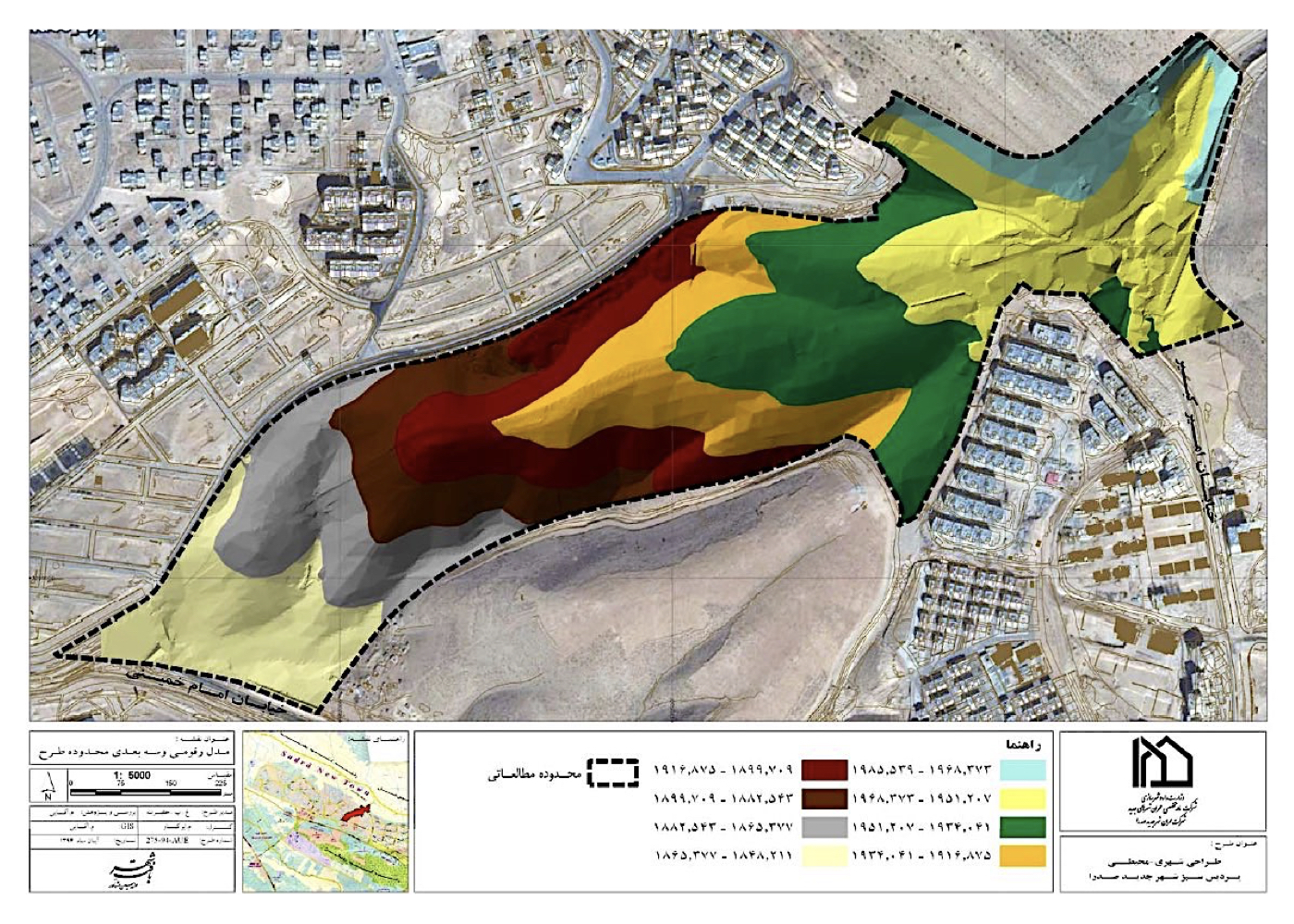

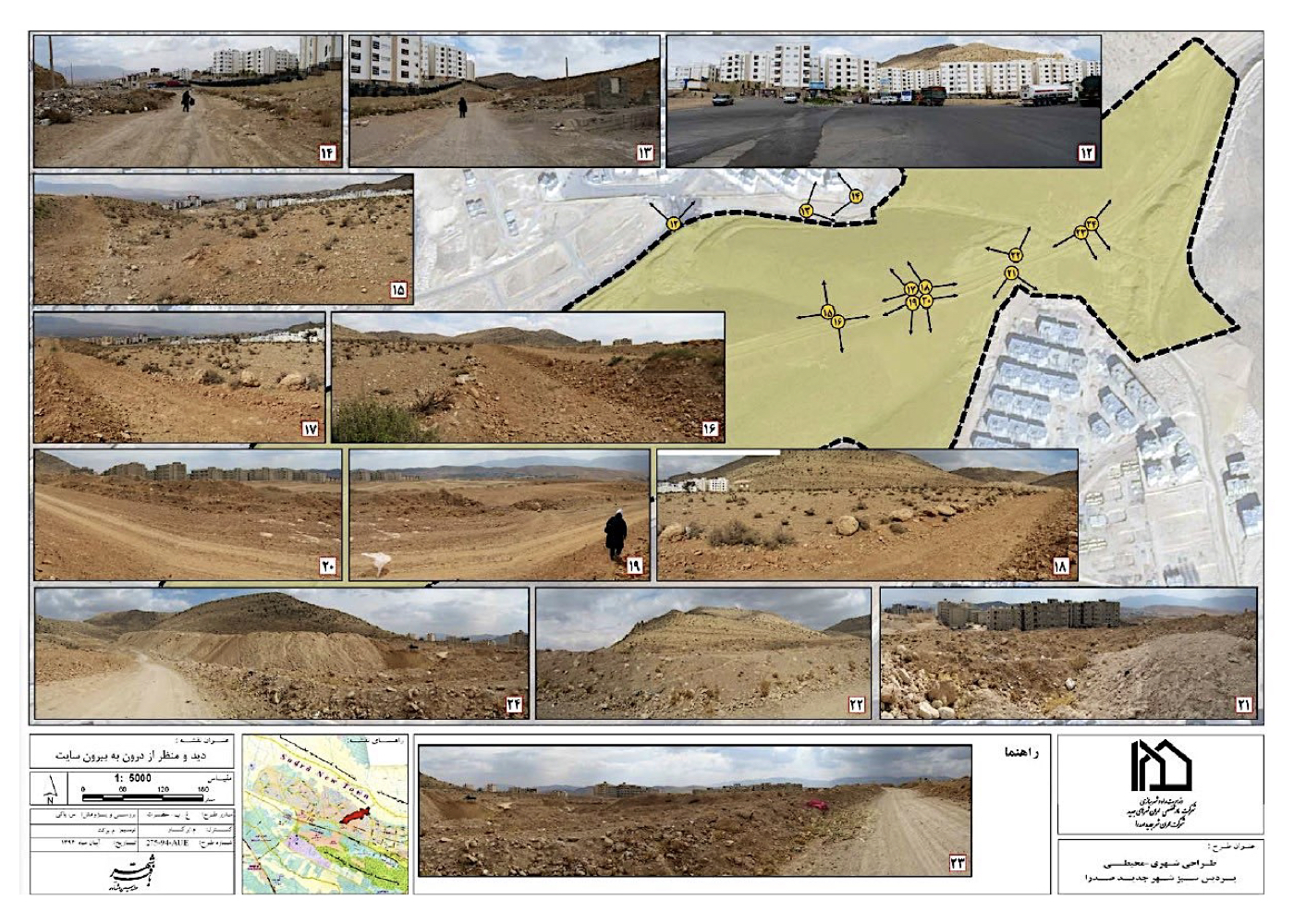

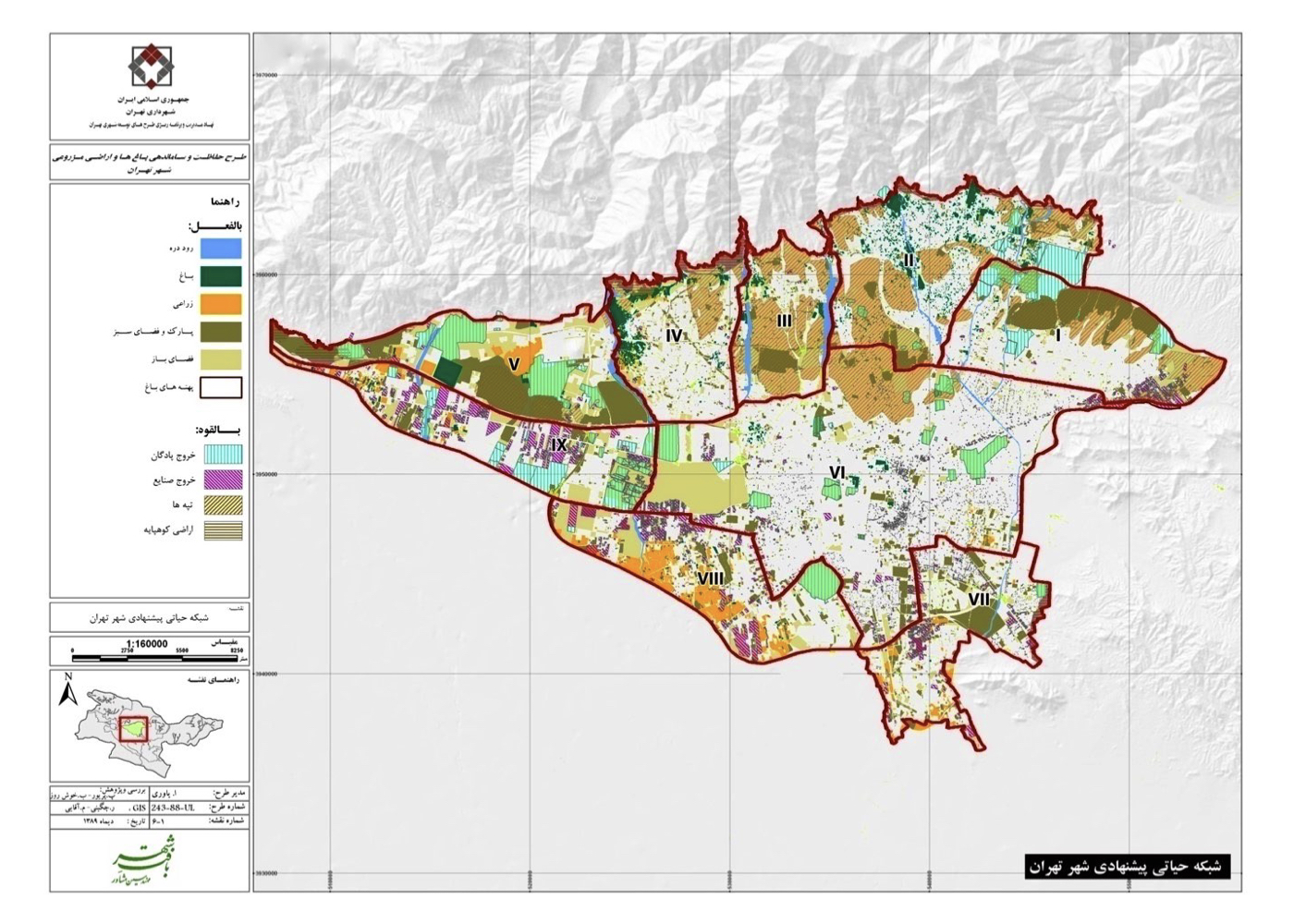

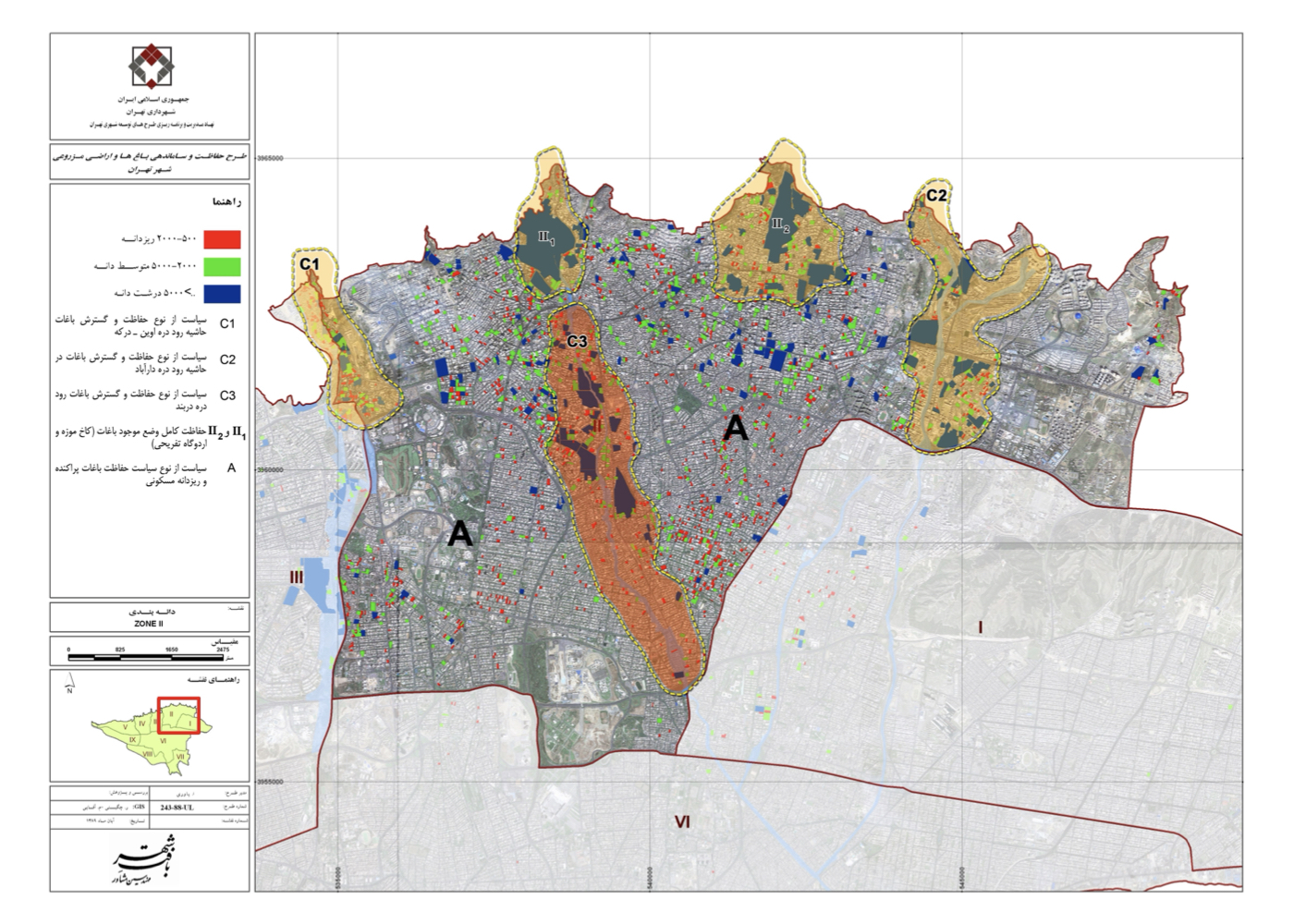

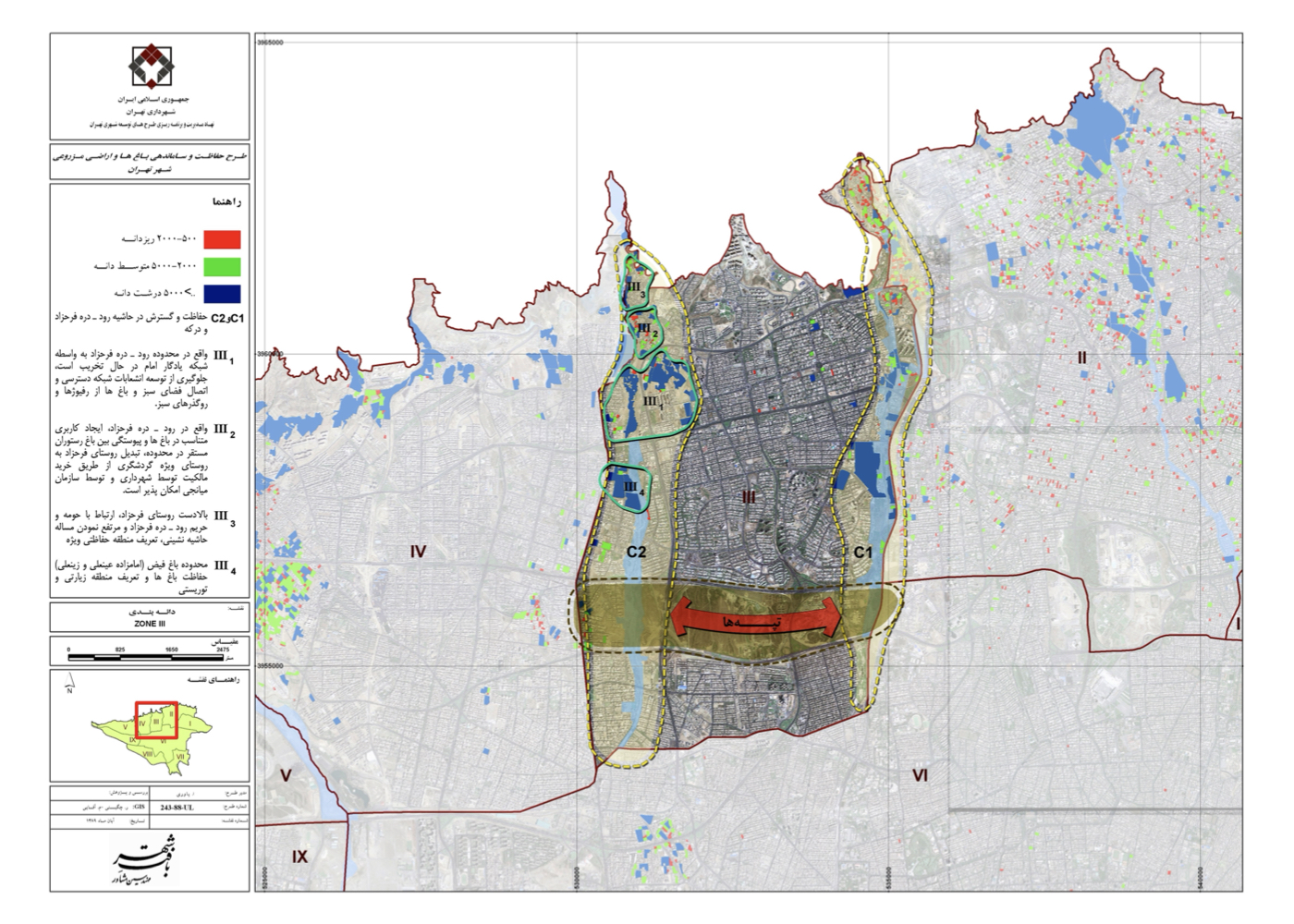

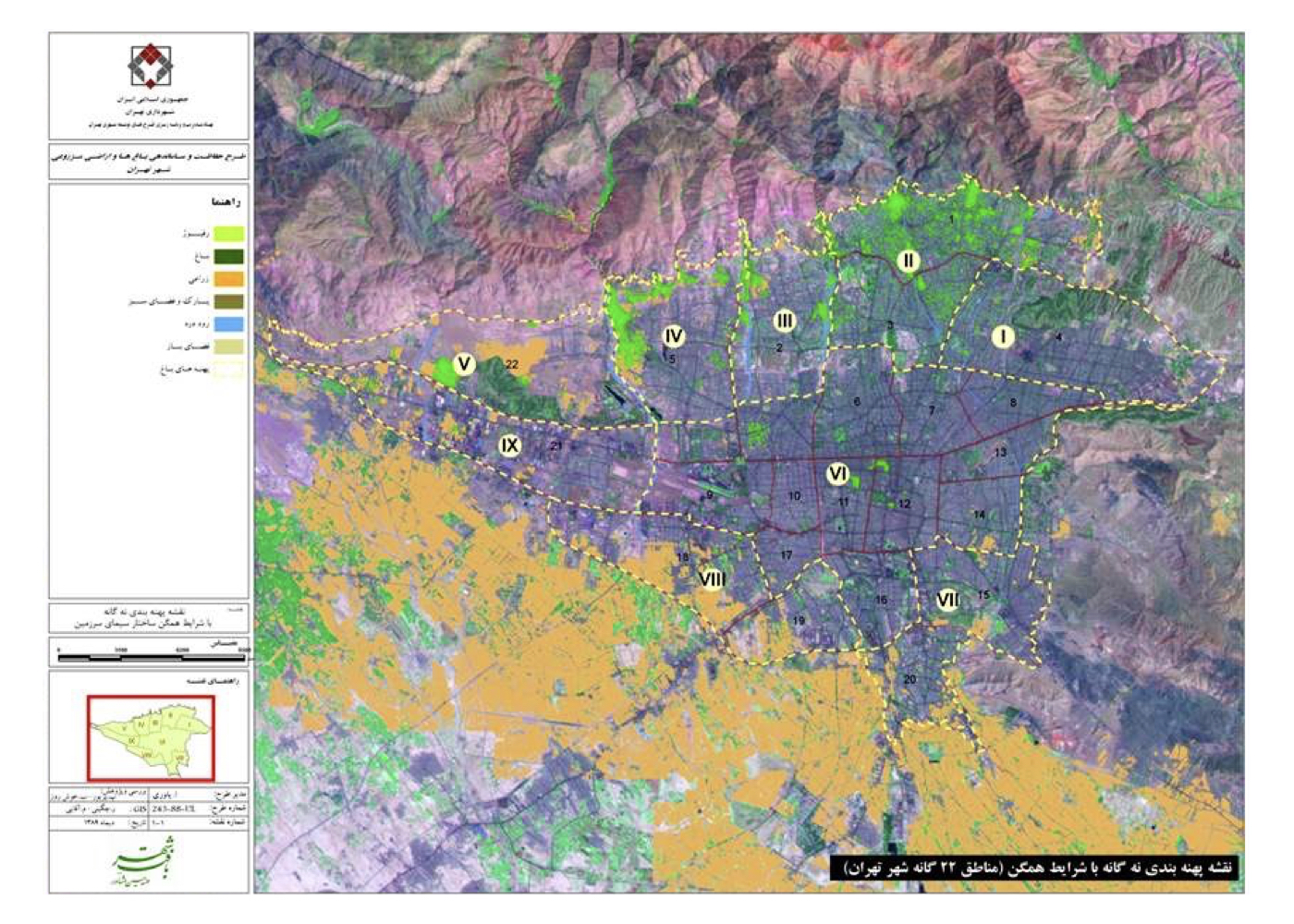

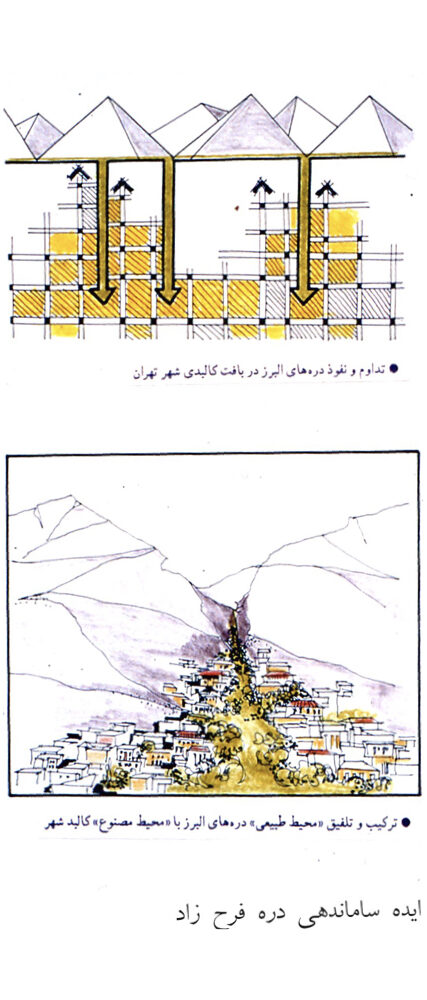

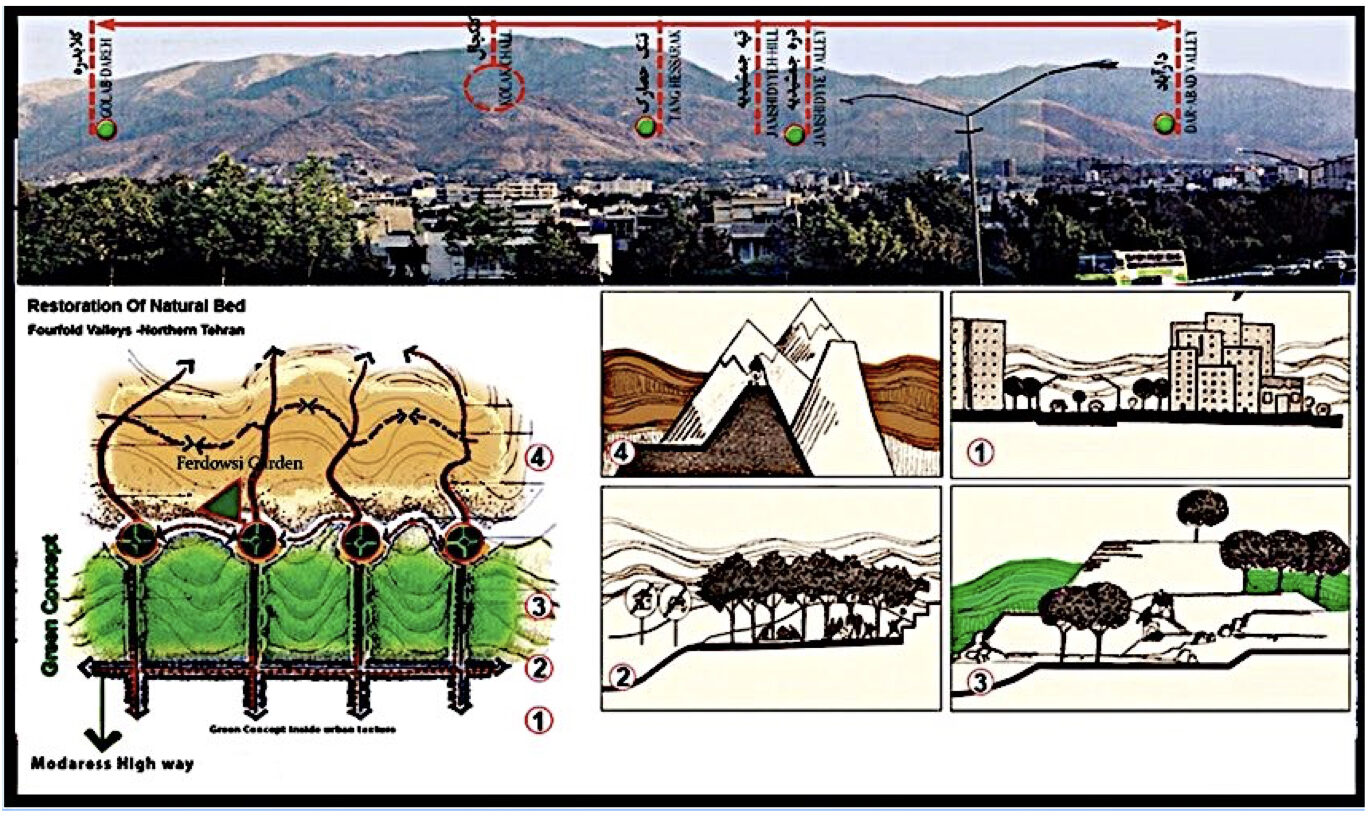

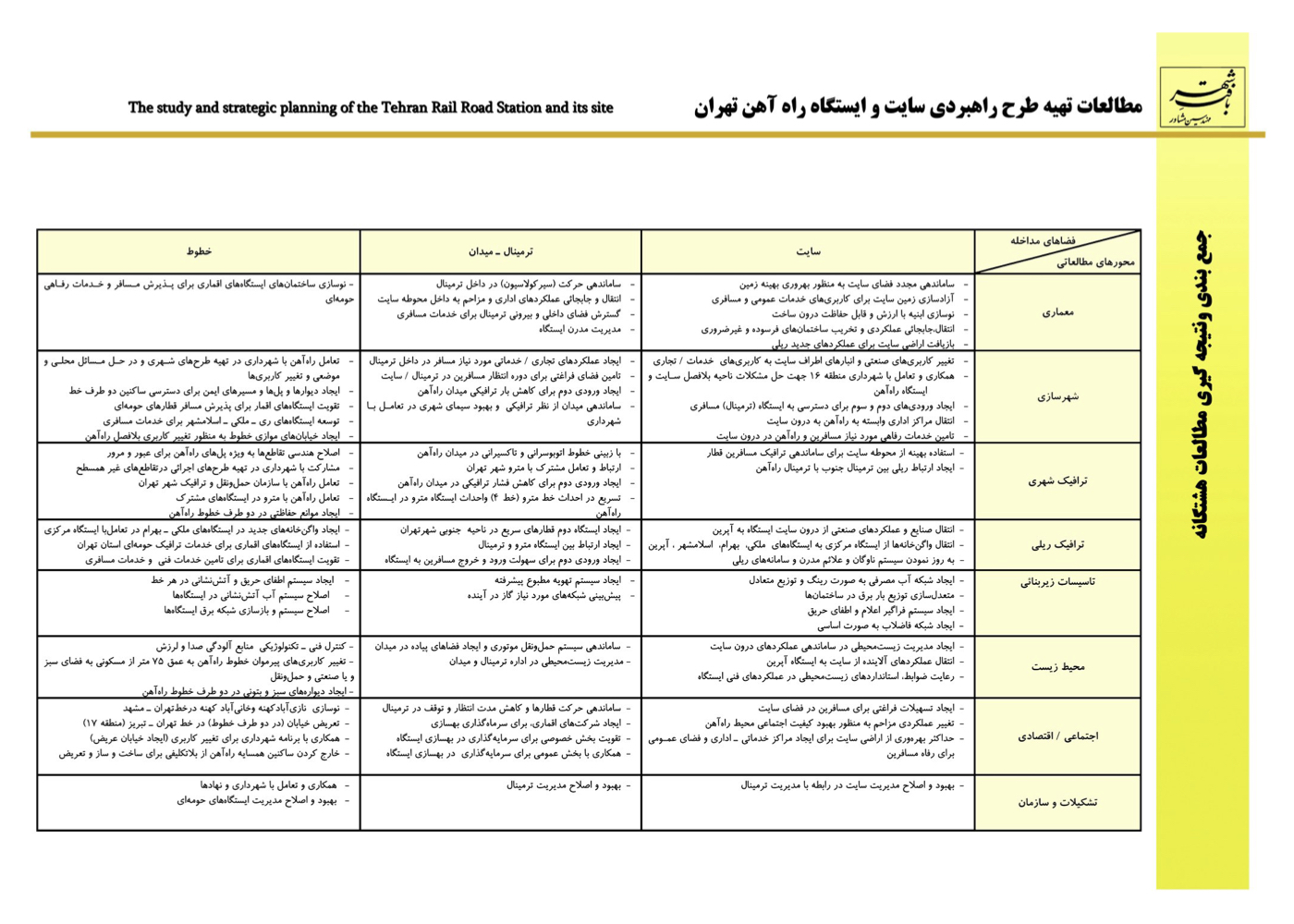

Wherever a city influences—or is influenced by—a natural element within or around its boundaries, all planning must prioritize rules, regulations, and guidelines rooted in environmental studies, landscape design, and related sciences—these must form the foundation for urban development plans in the domains of urbanism, urban design, and allied disciplines.

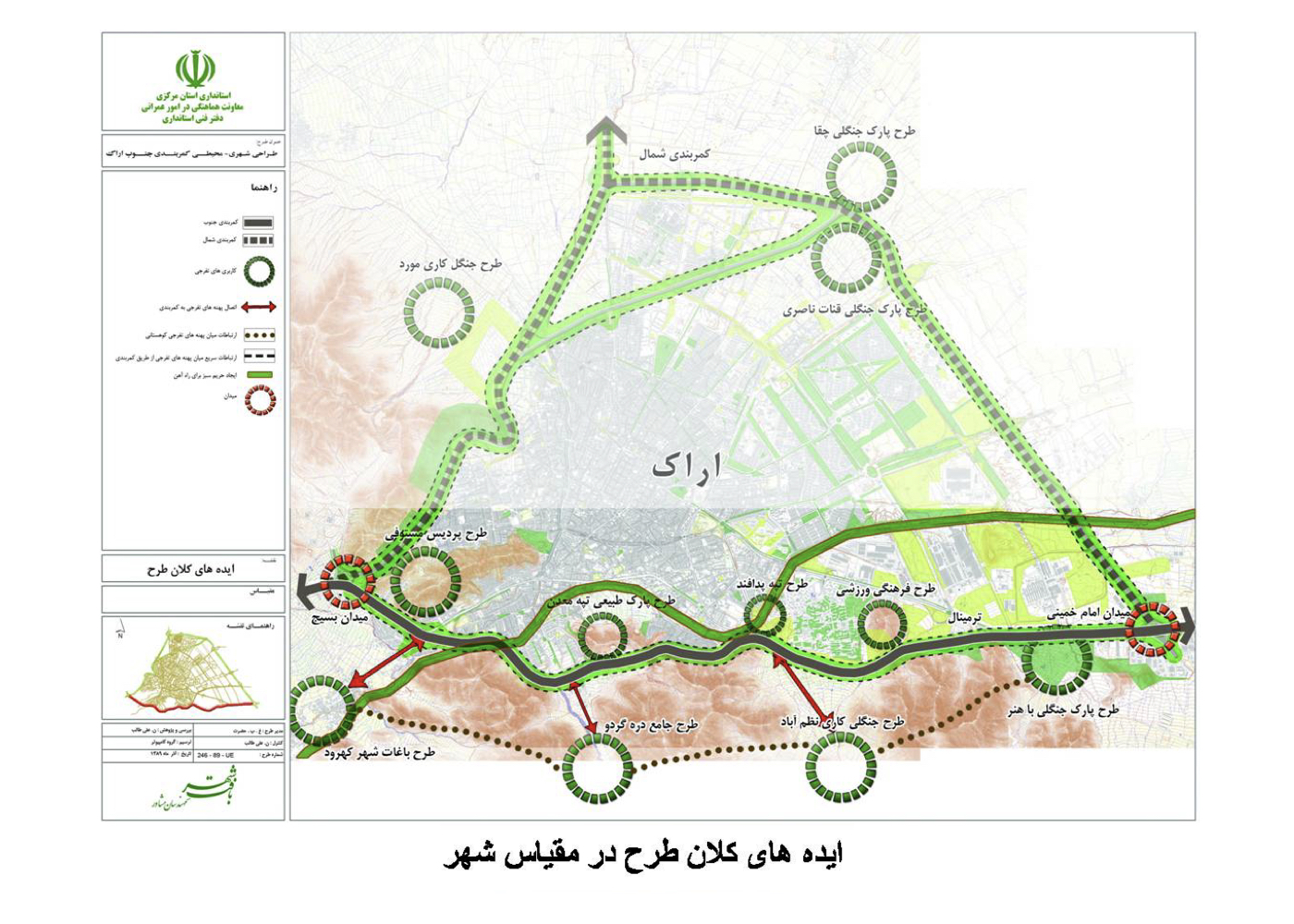

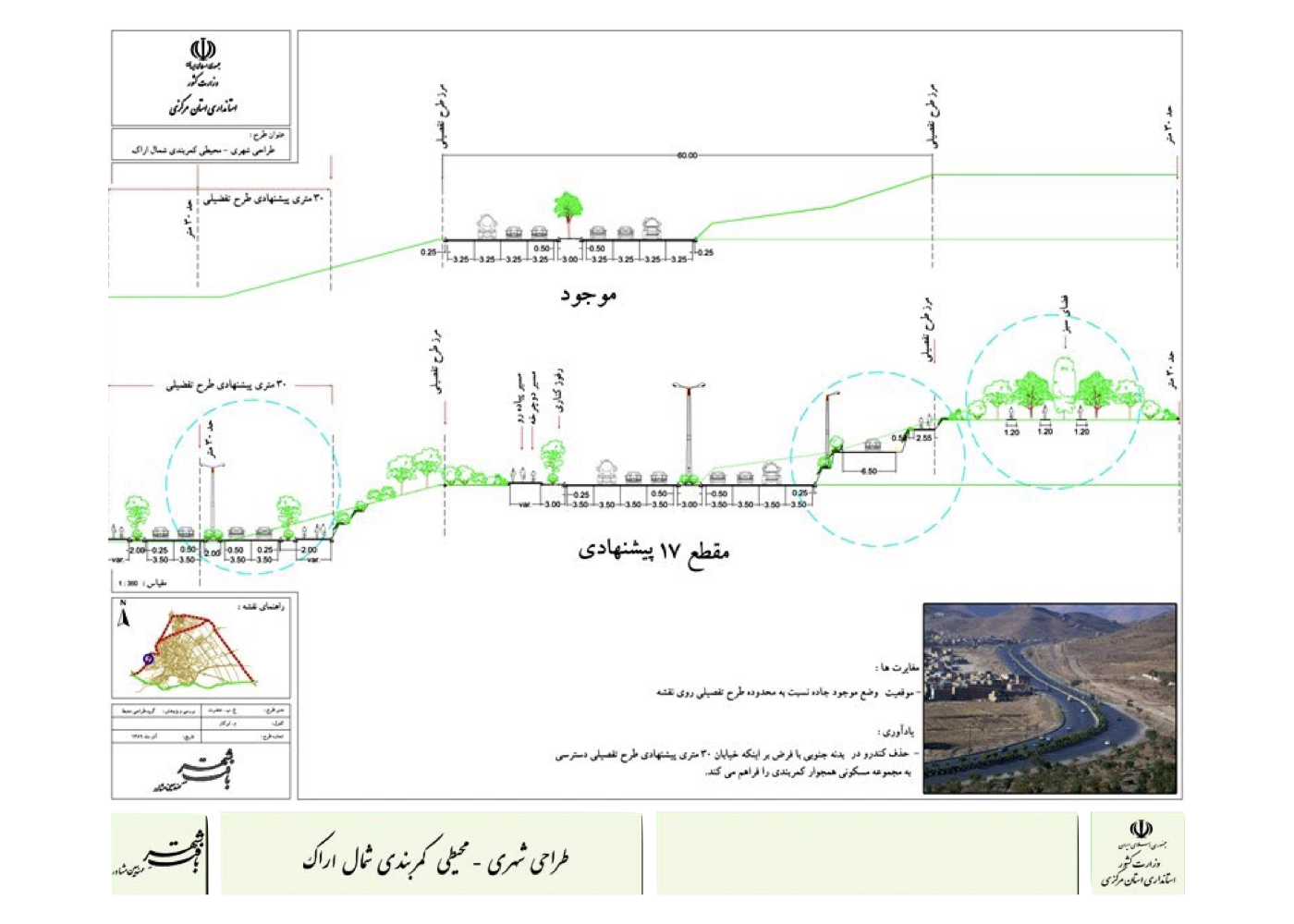

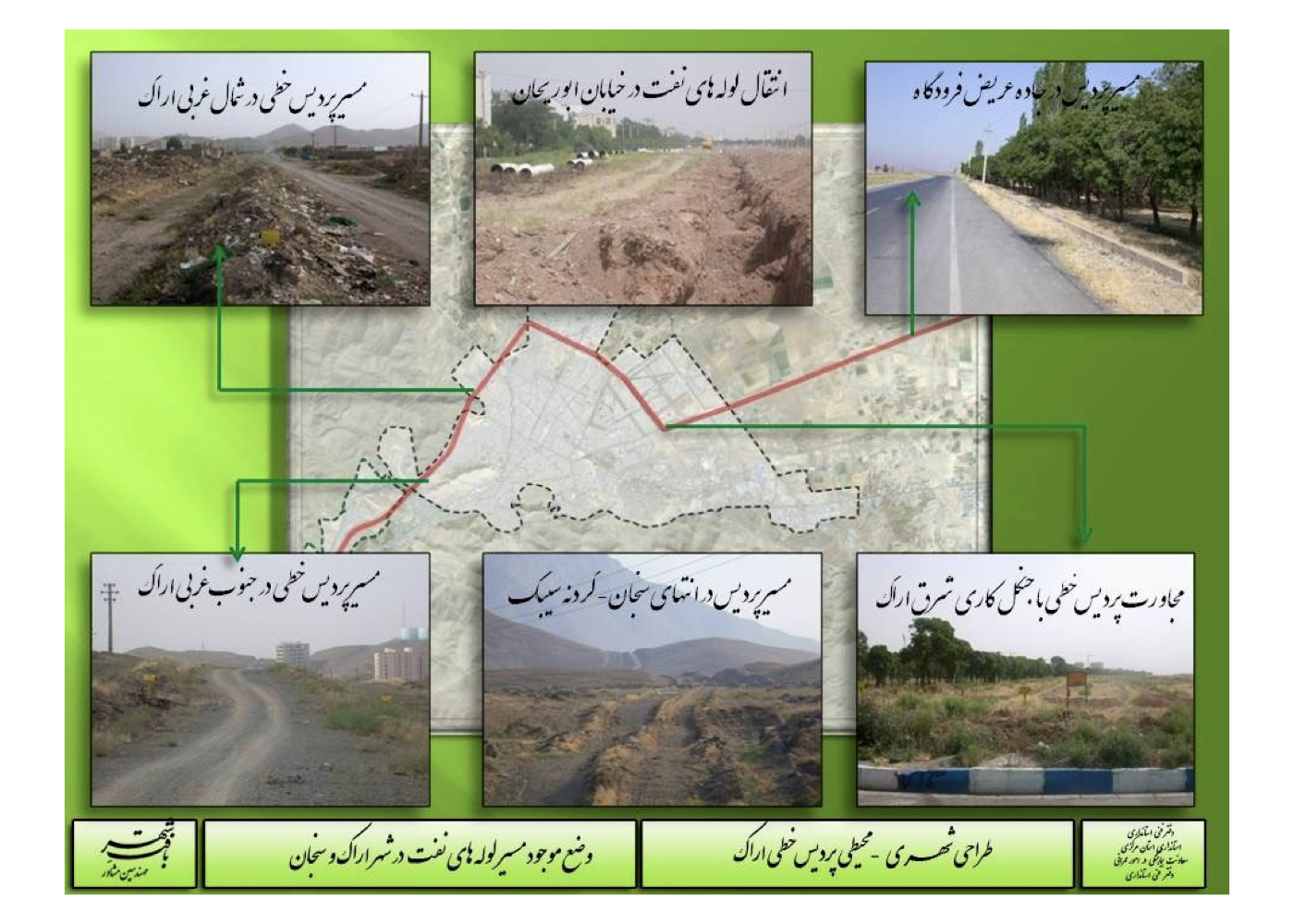

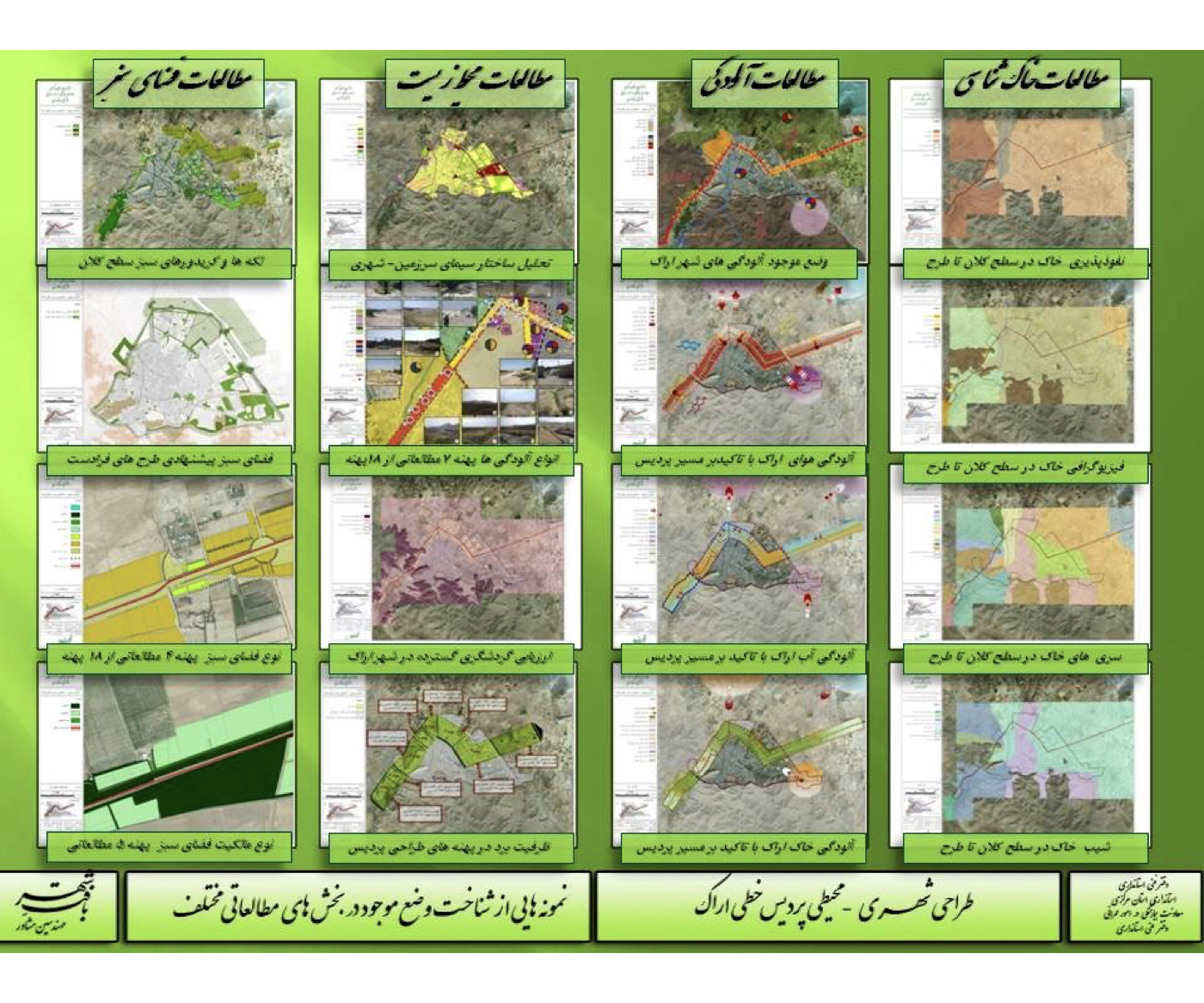

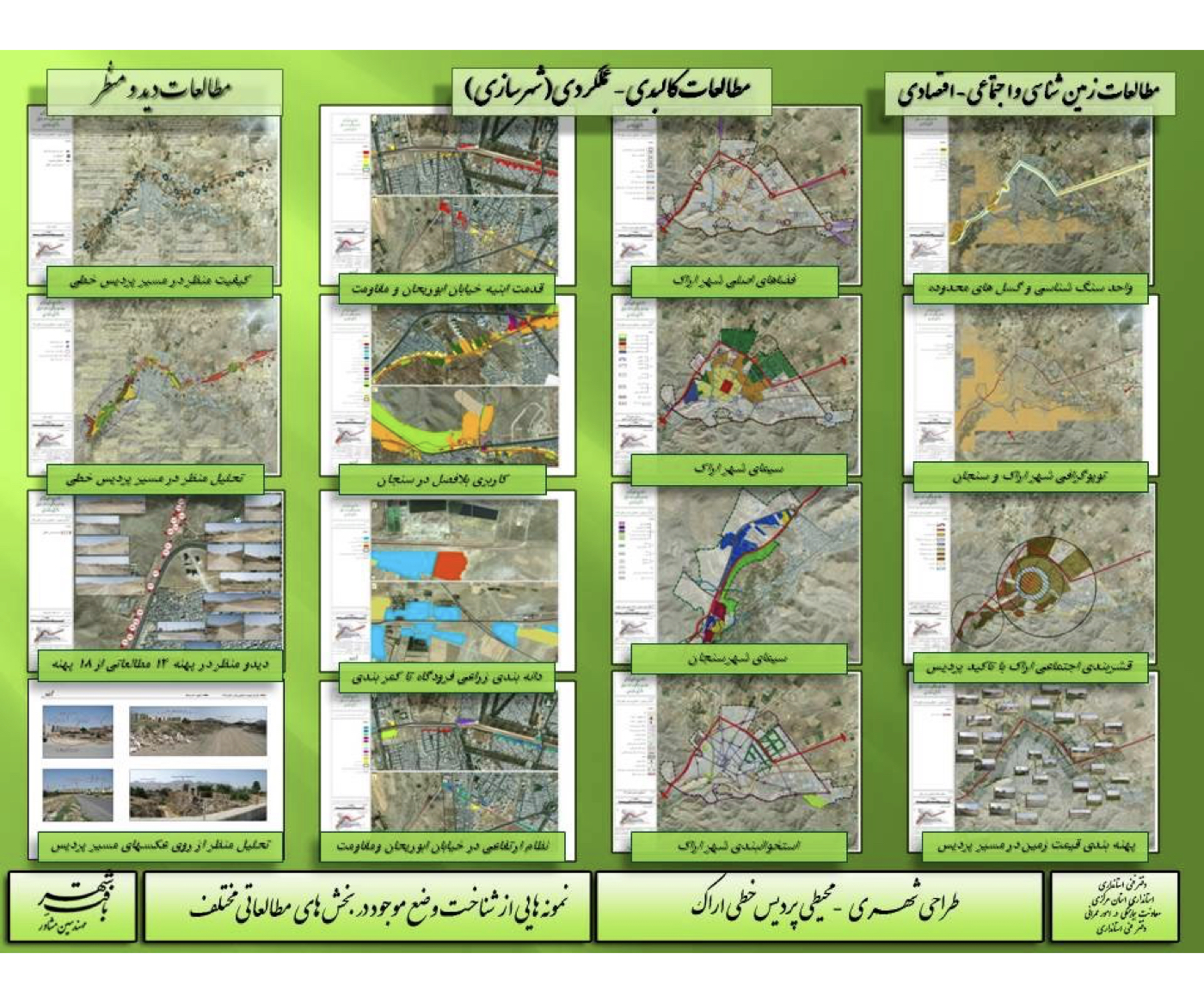

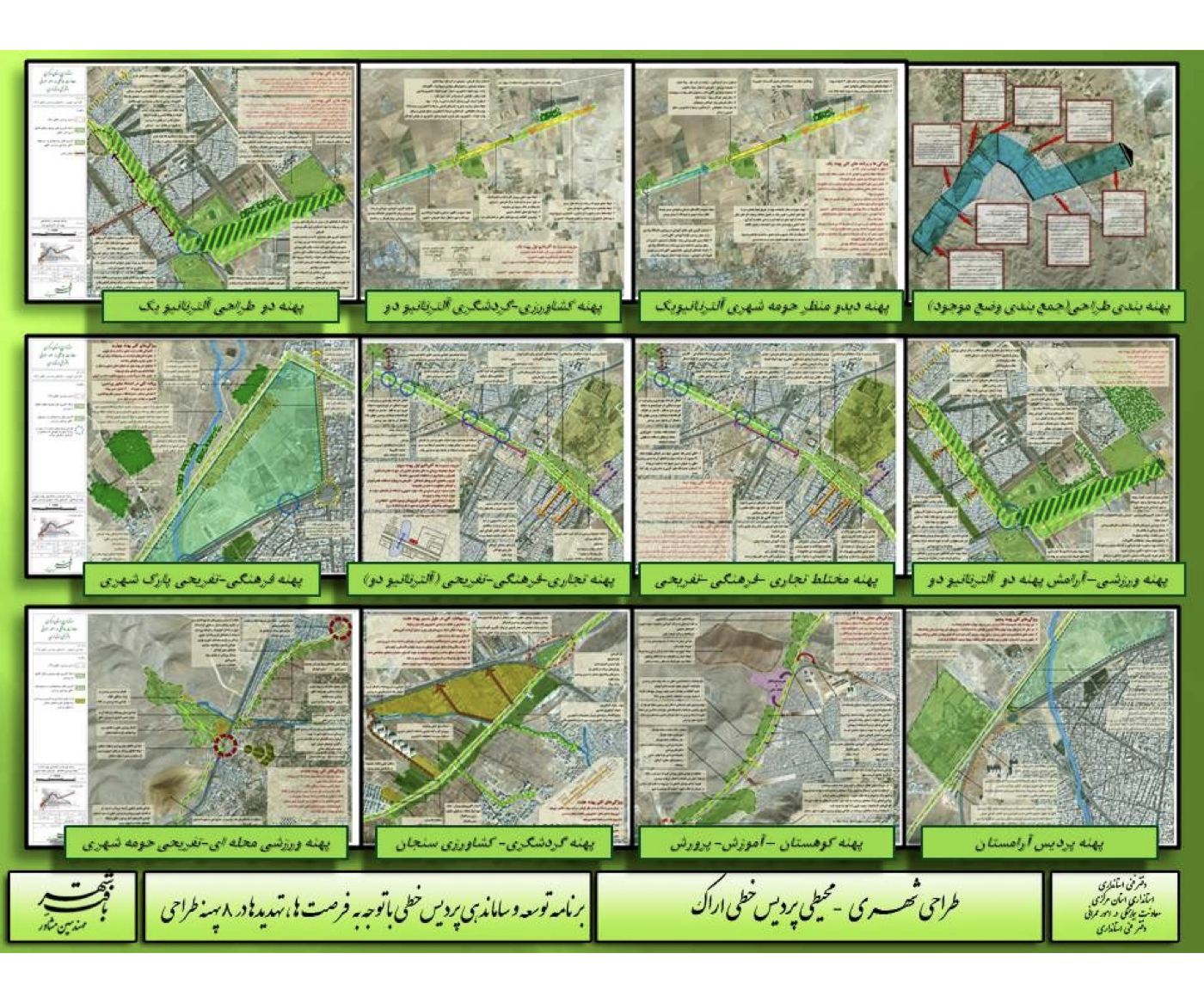

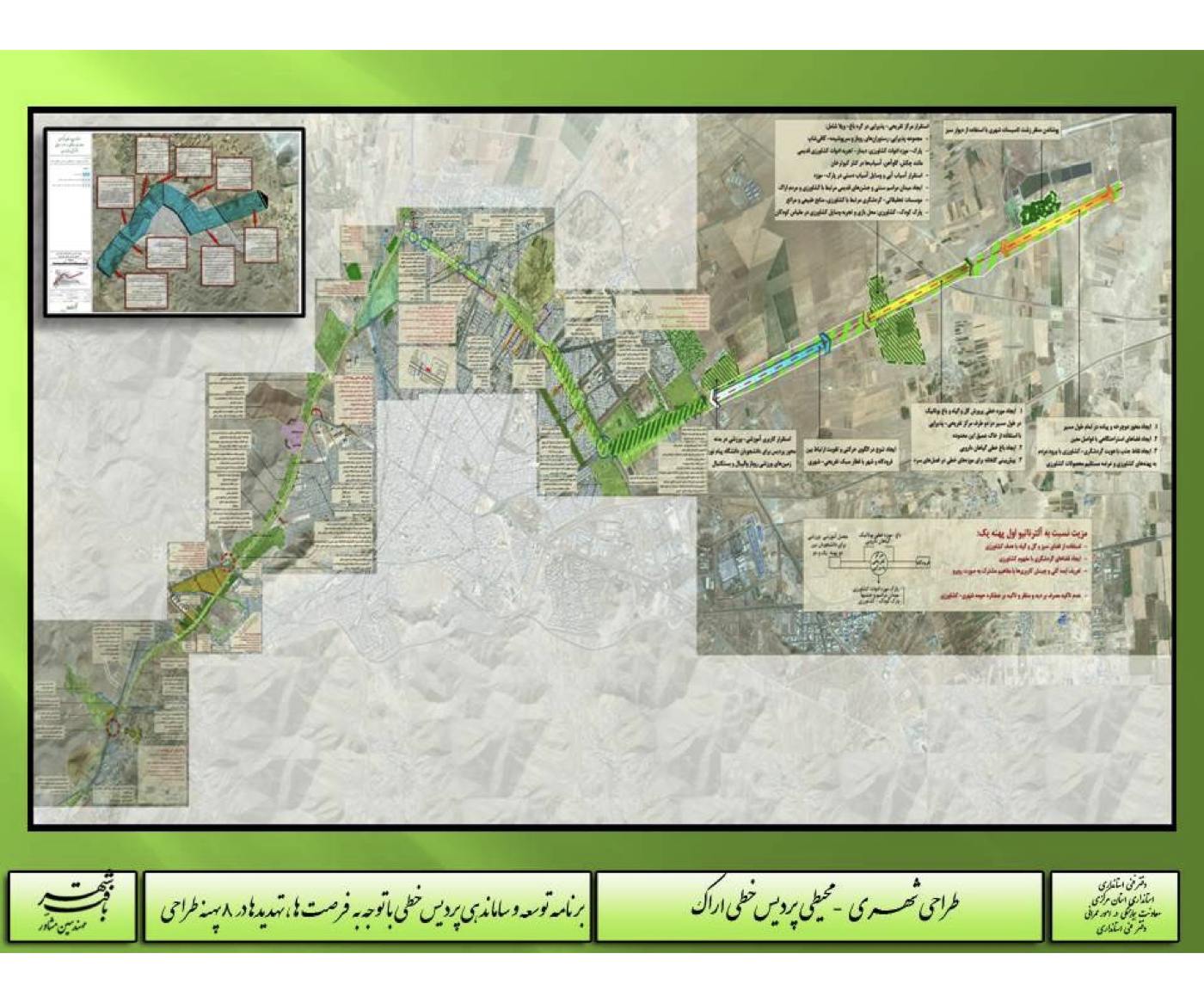

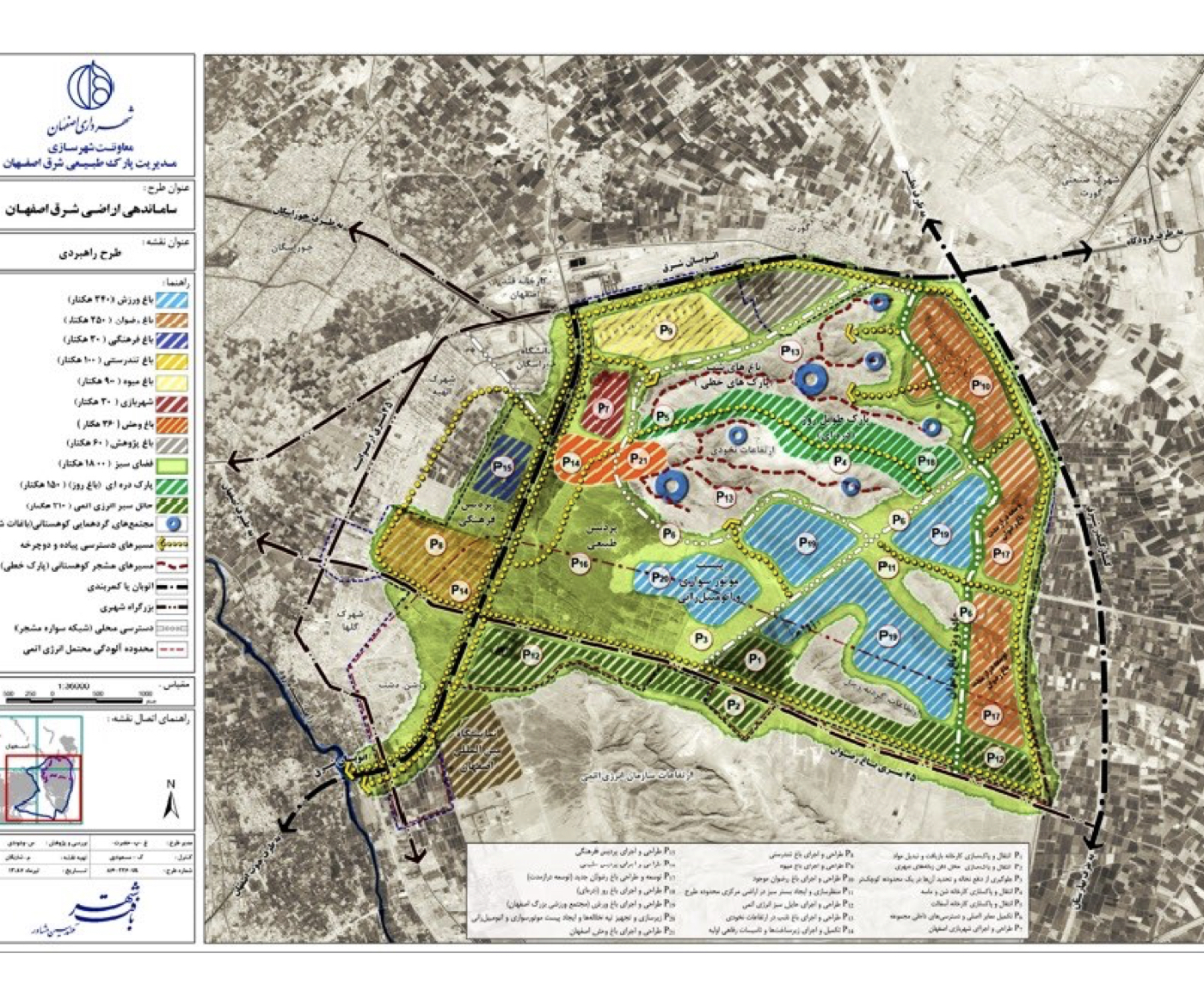

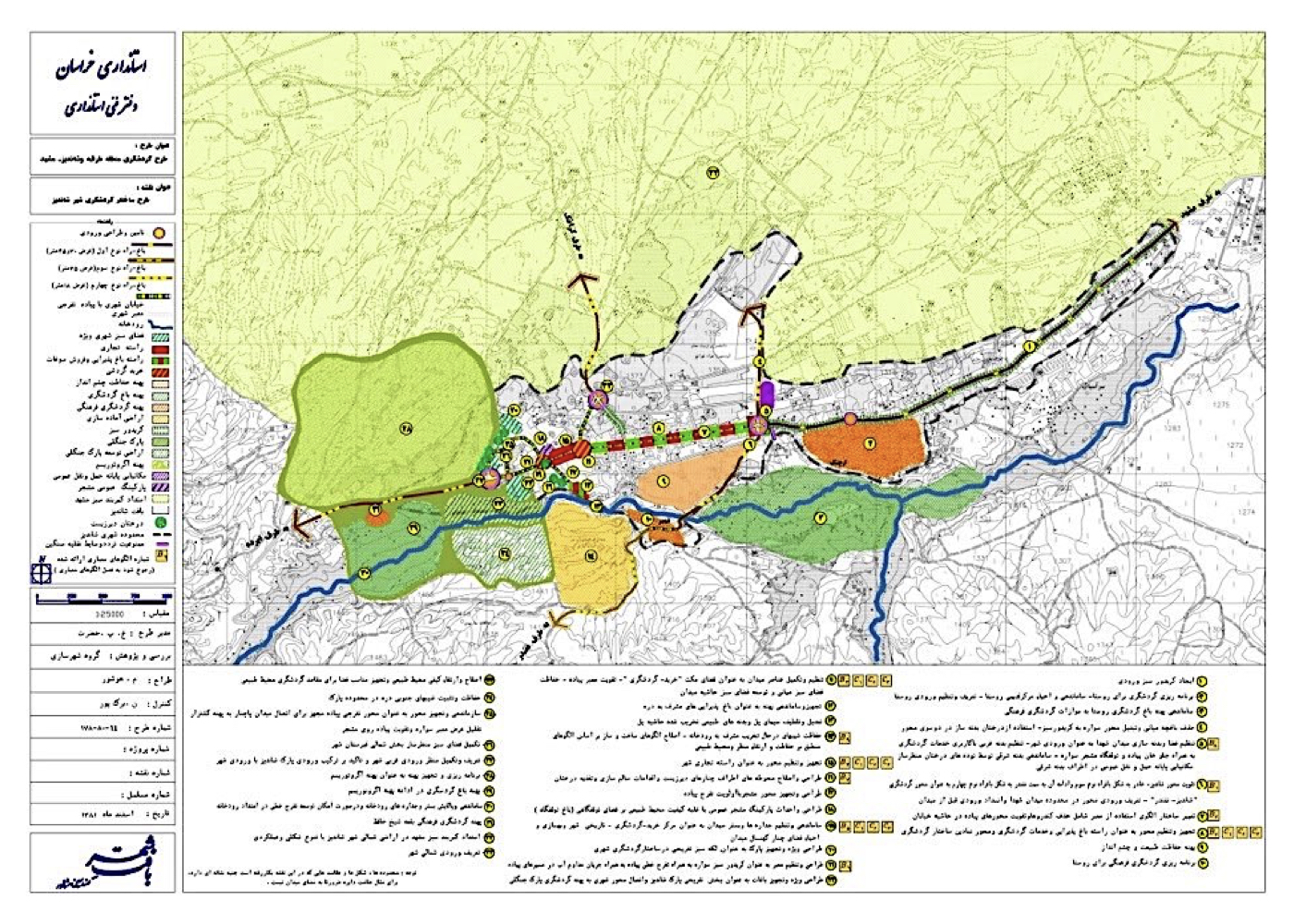

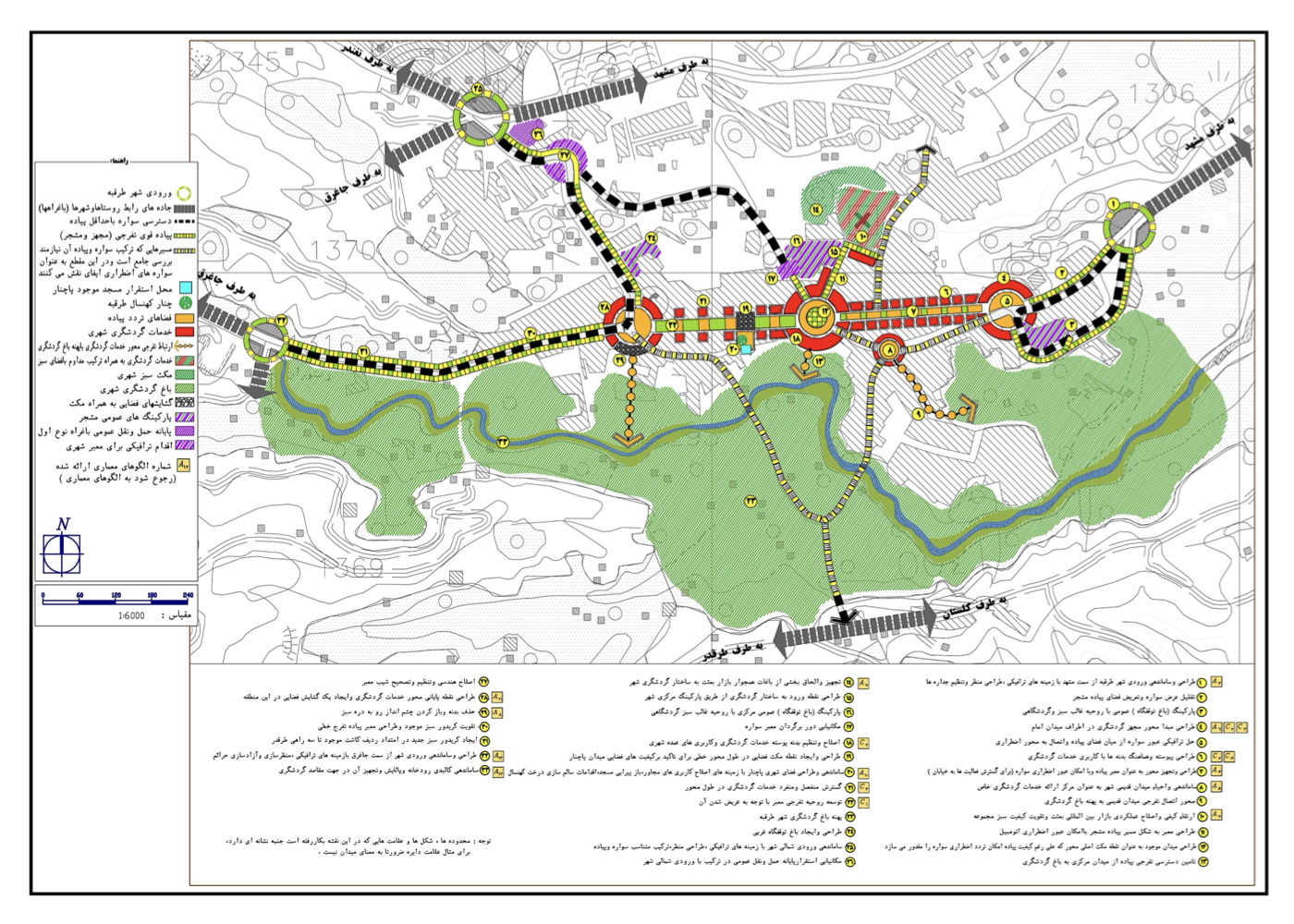

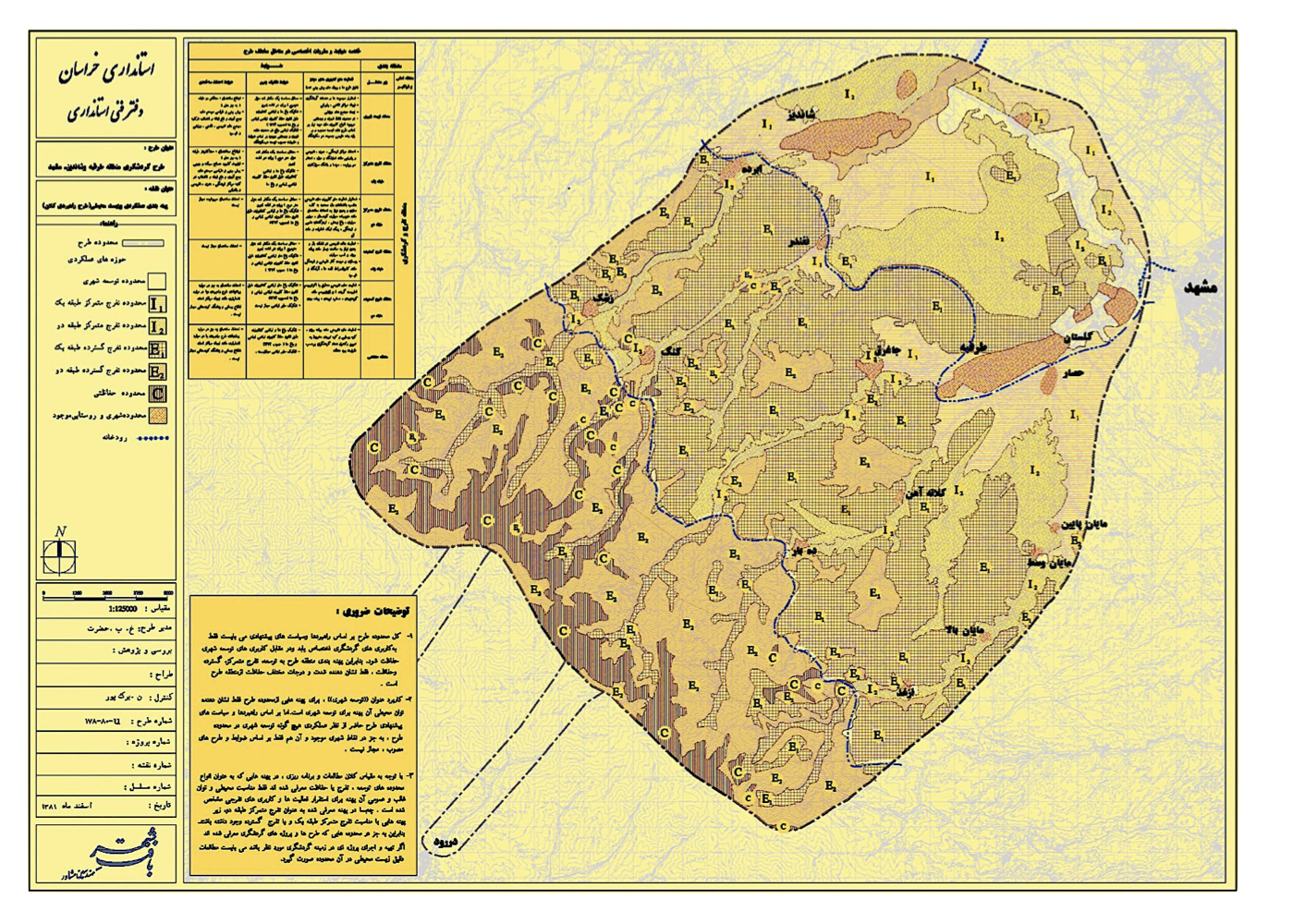

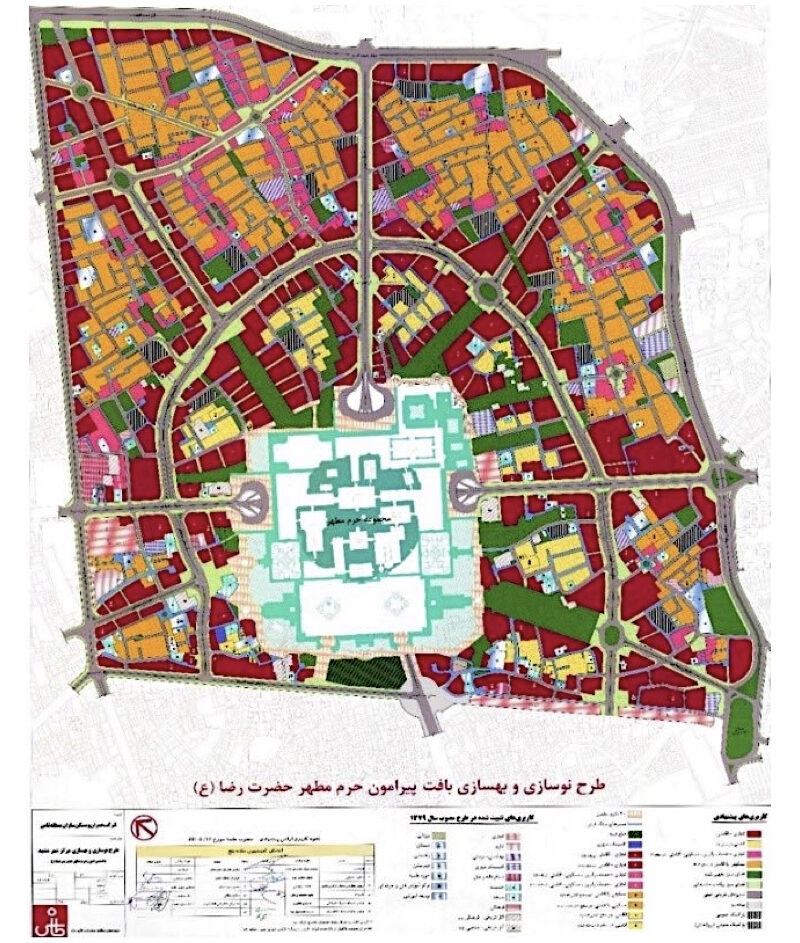

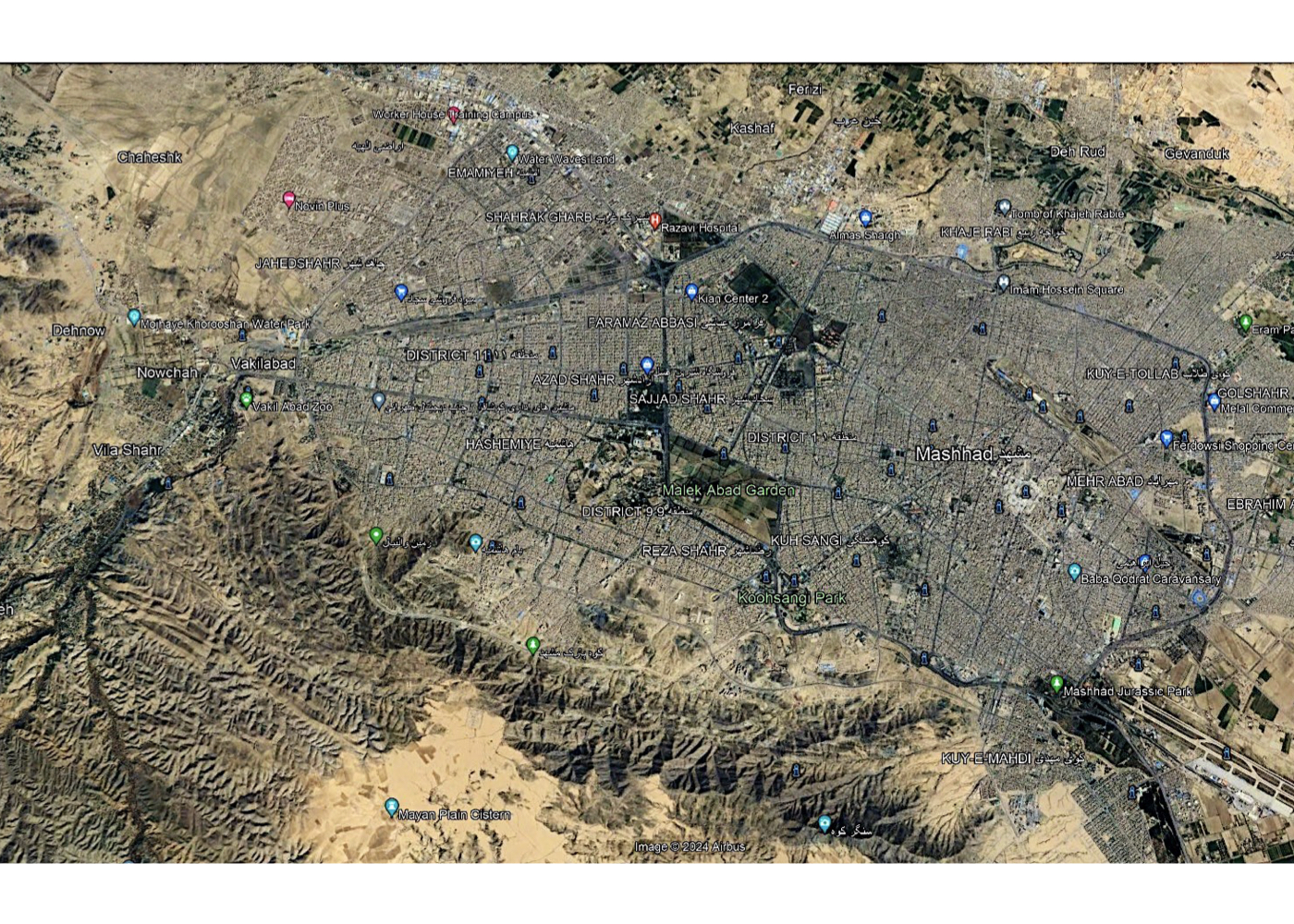

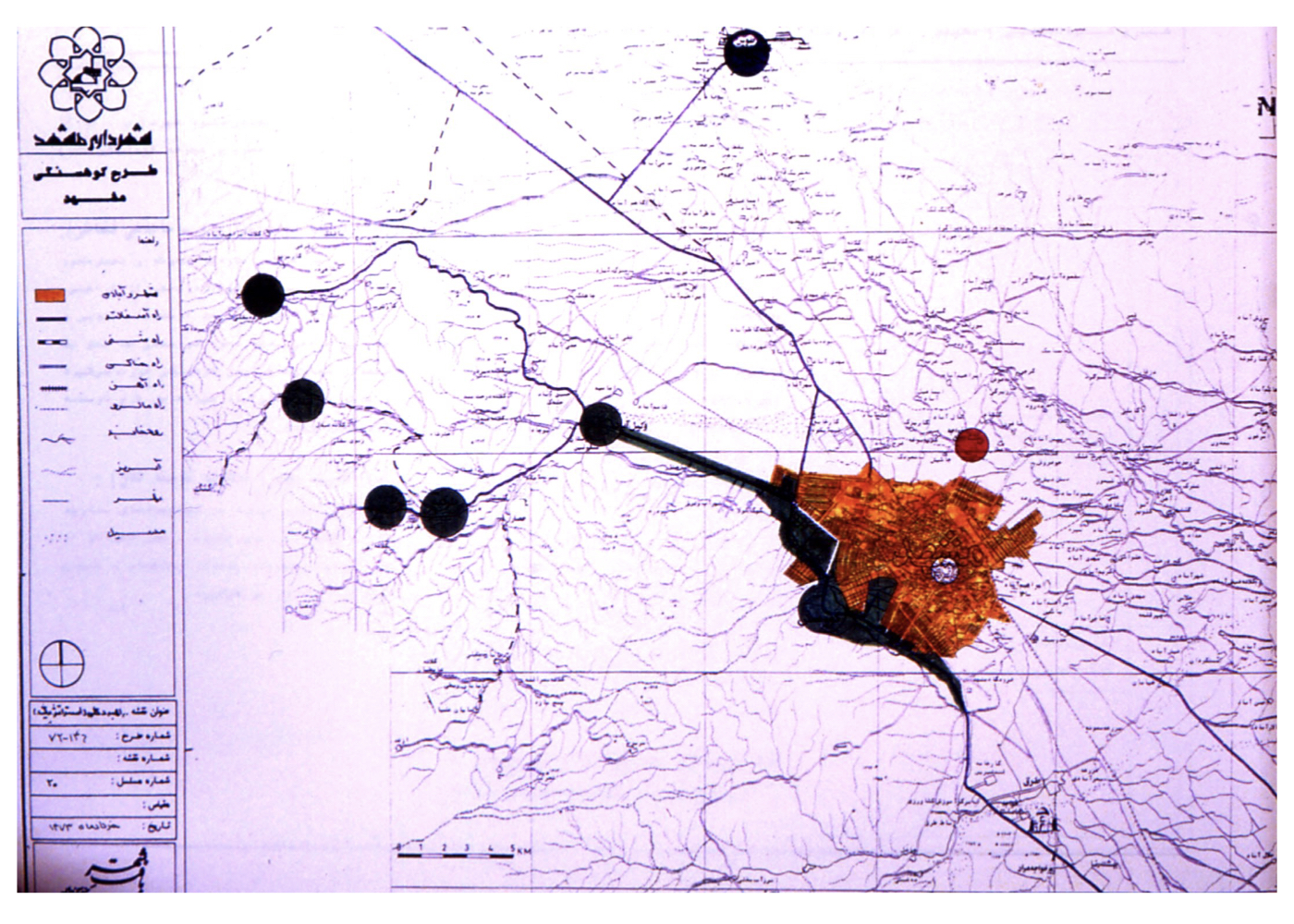

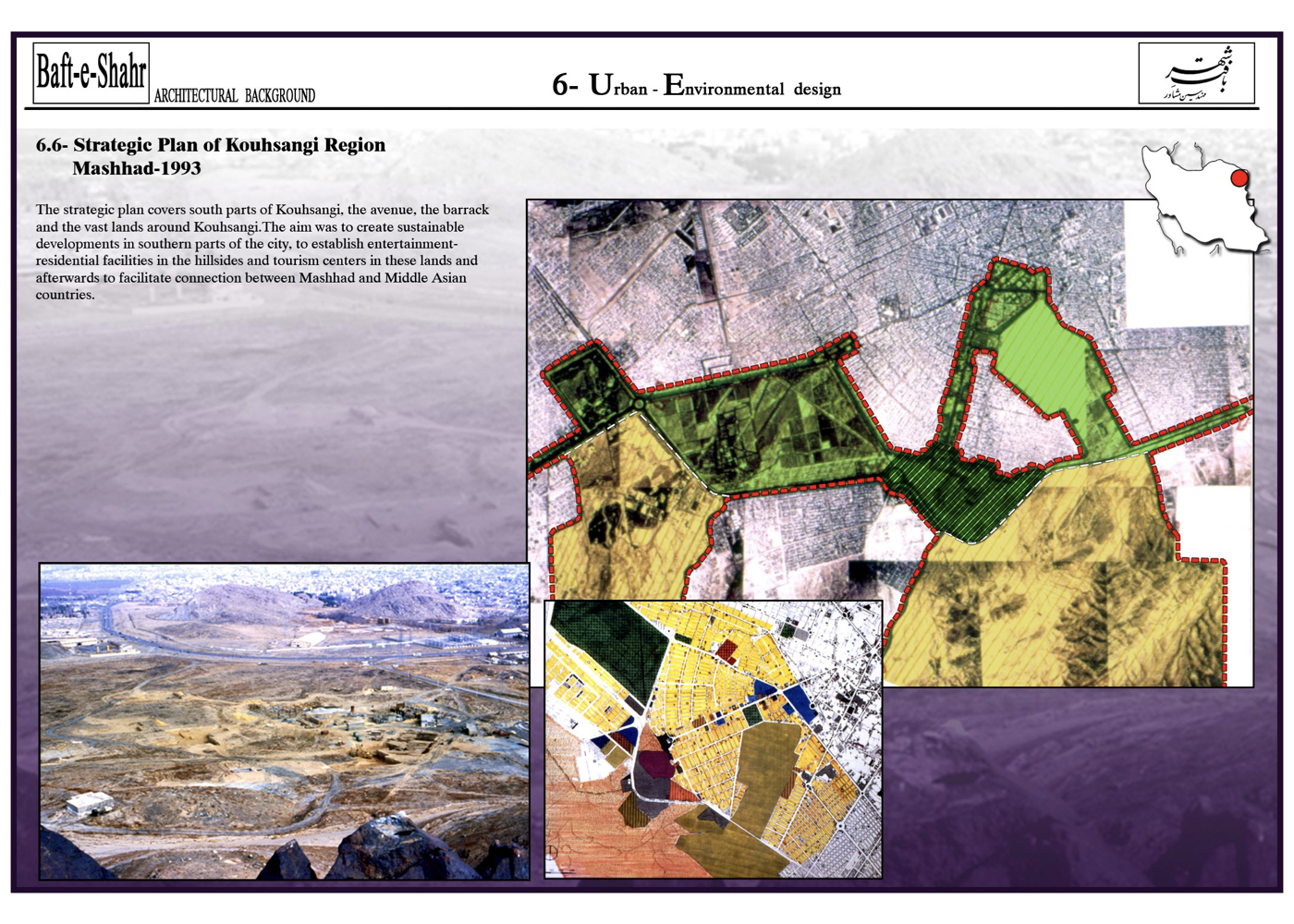

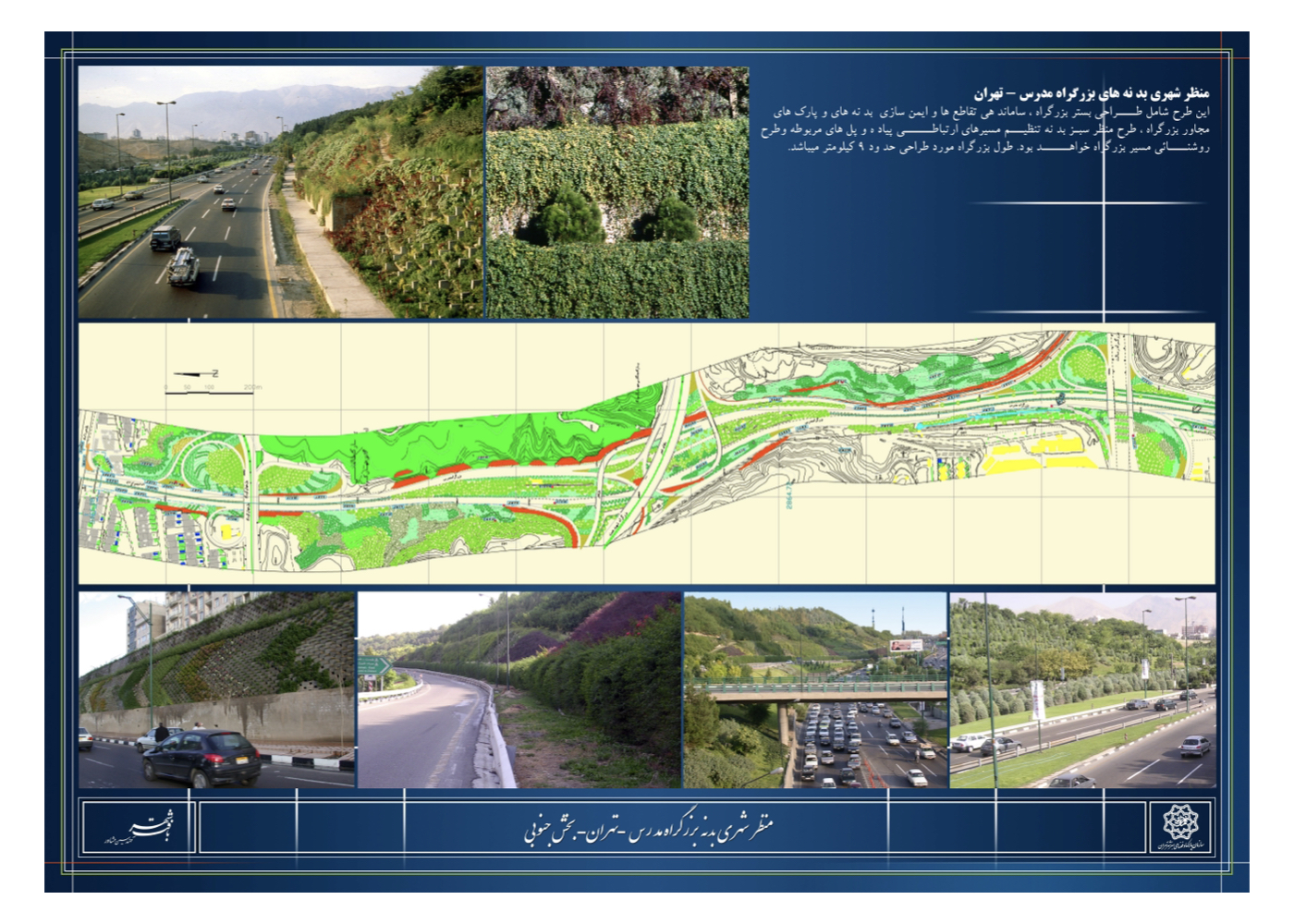

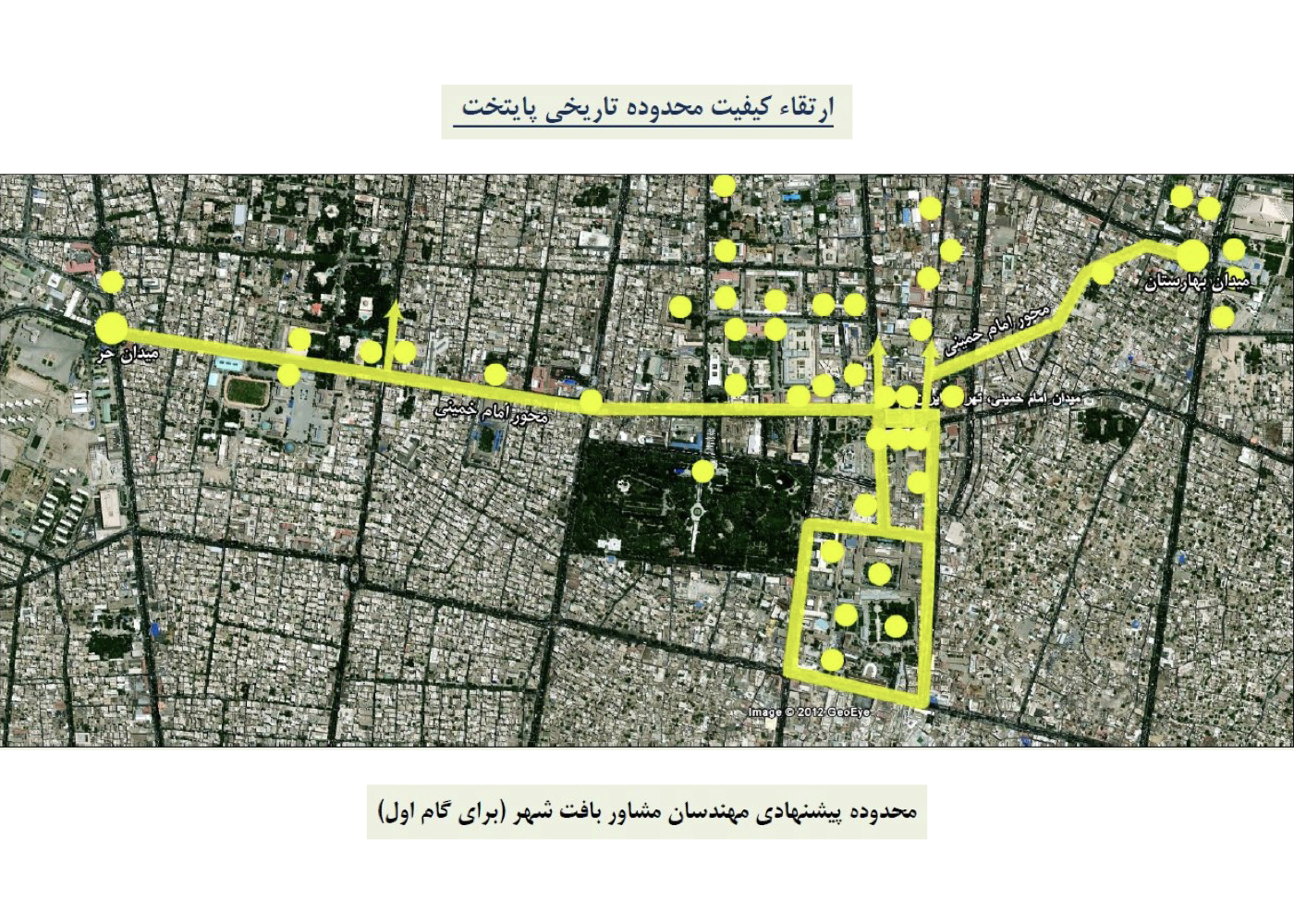

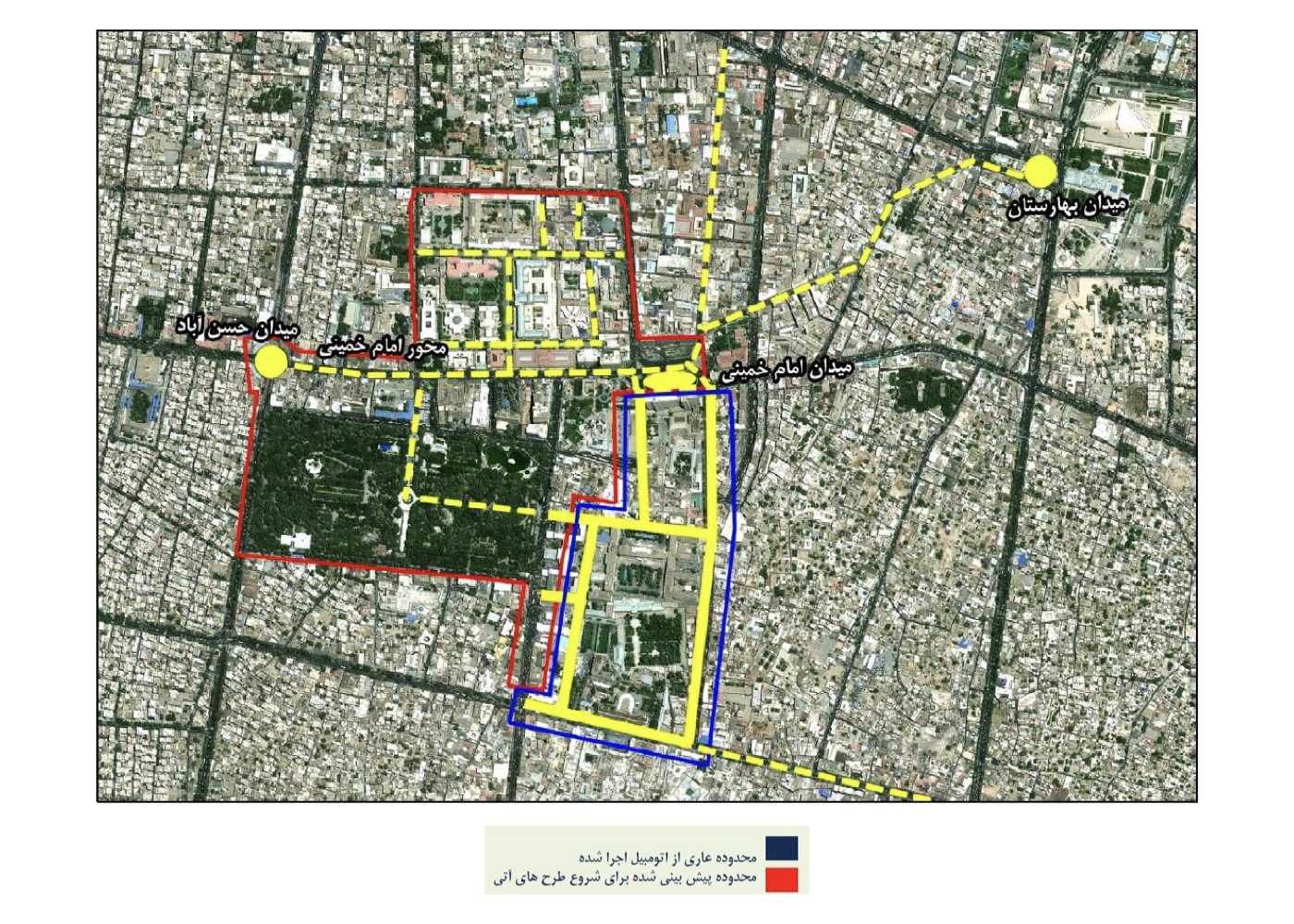

Achievements of the Urban–Environmental Design Theory in Iran:

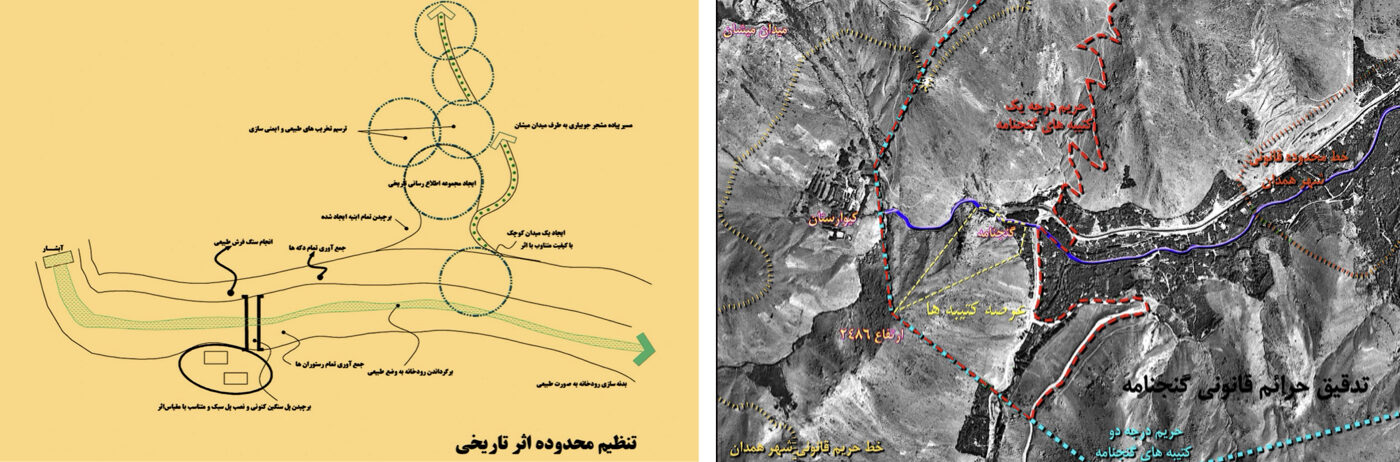

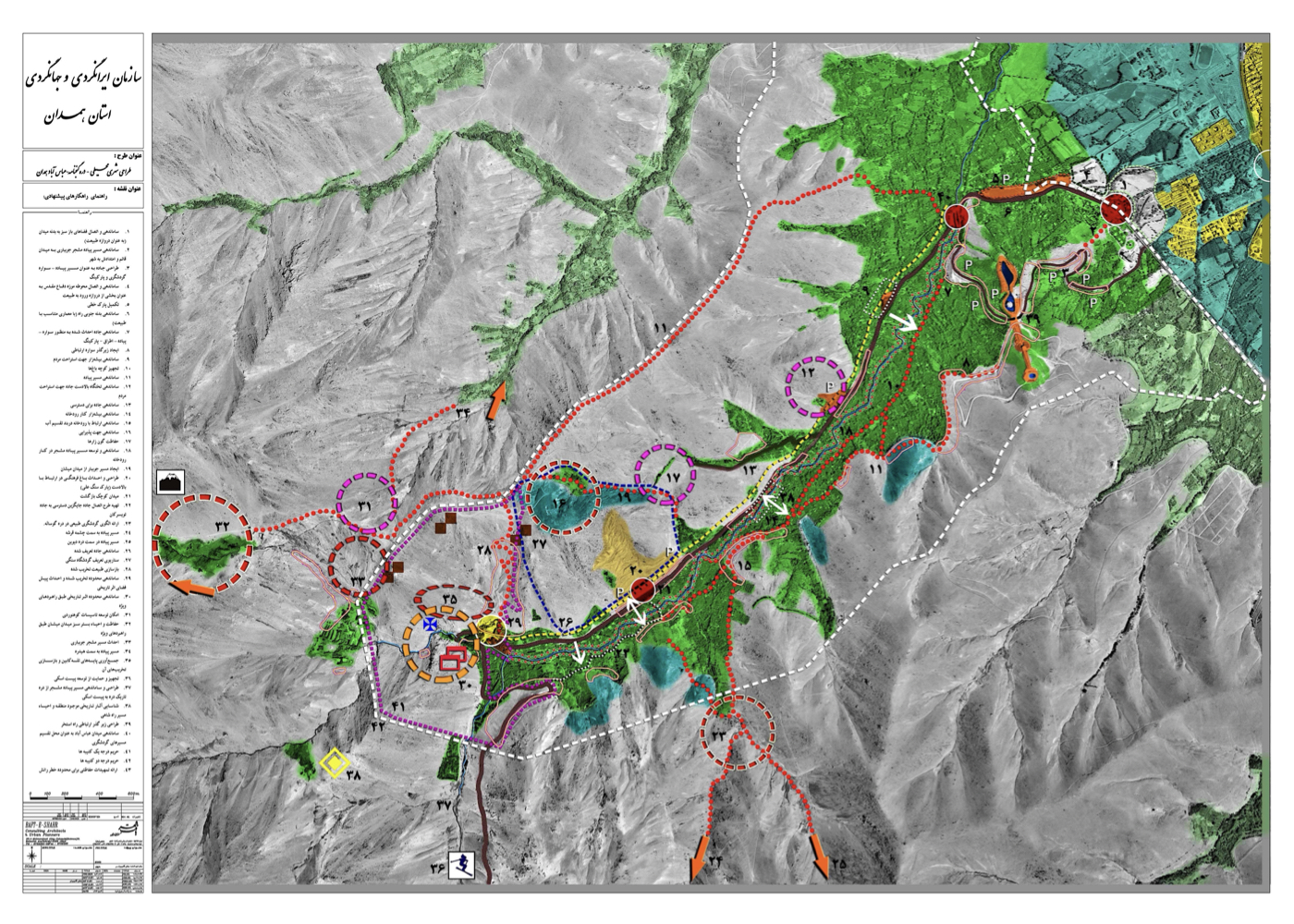

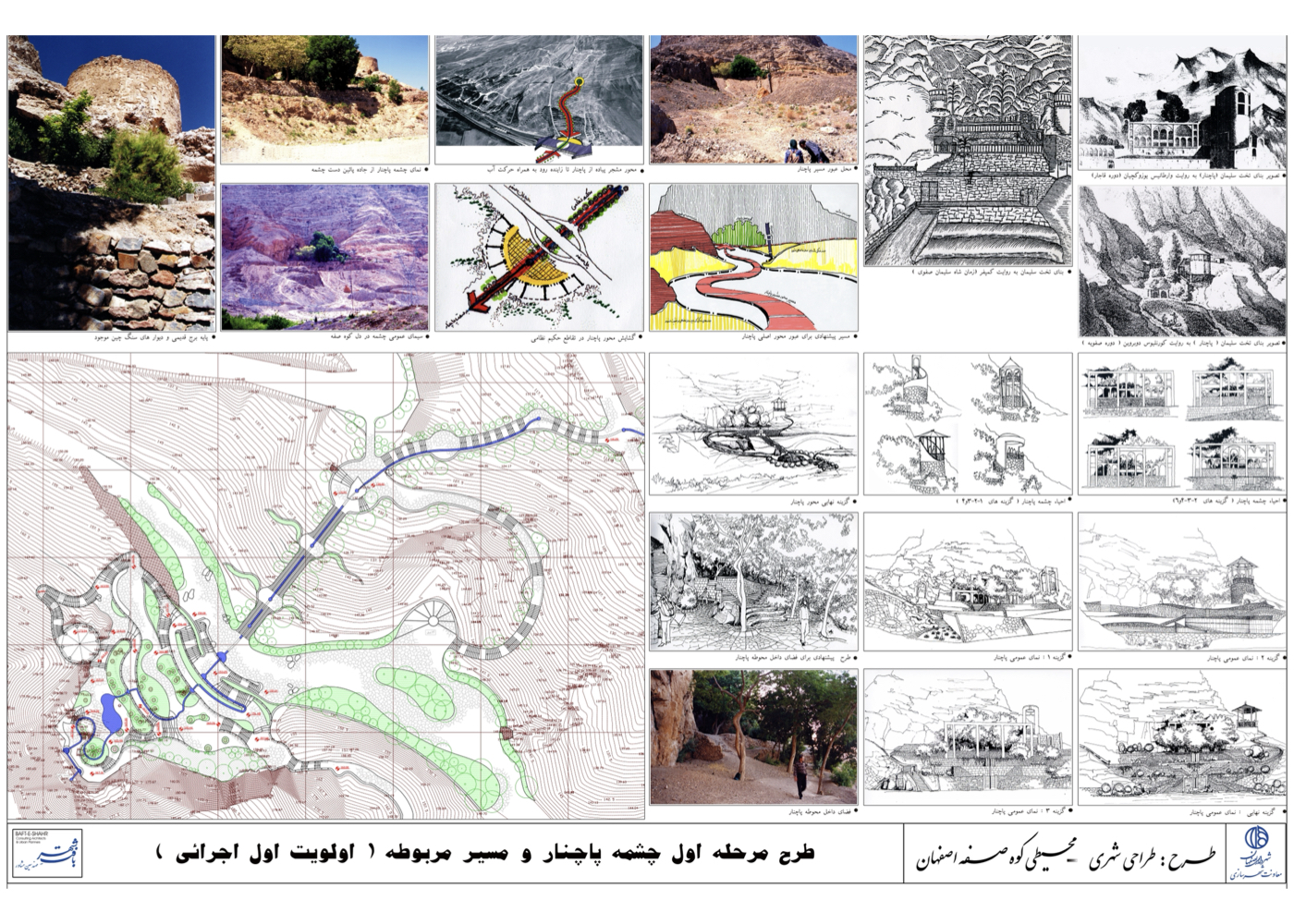

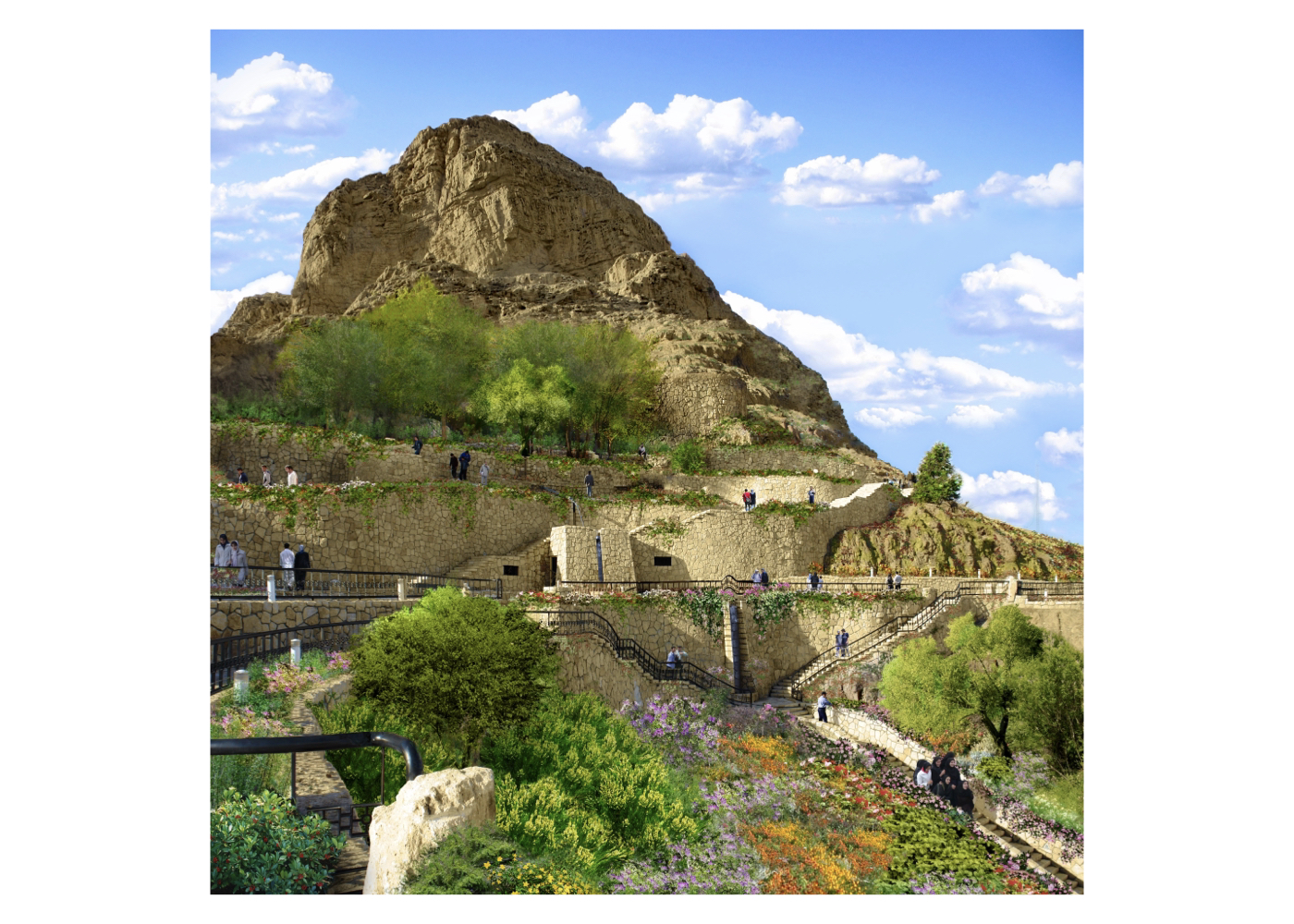

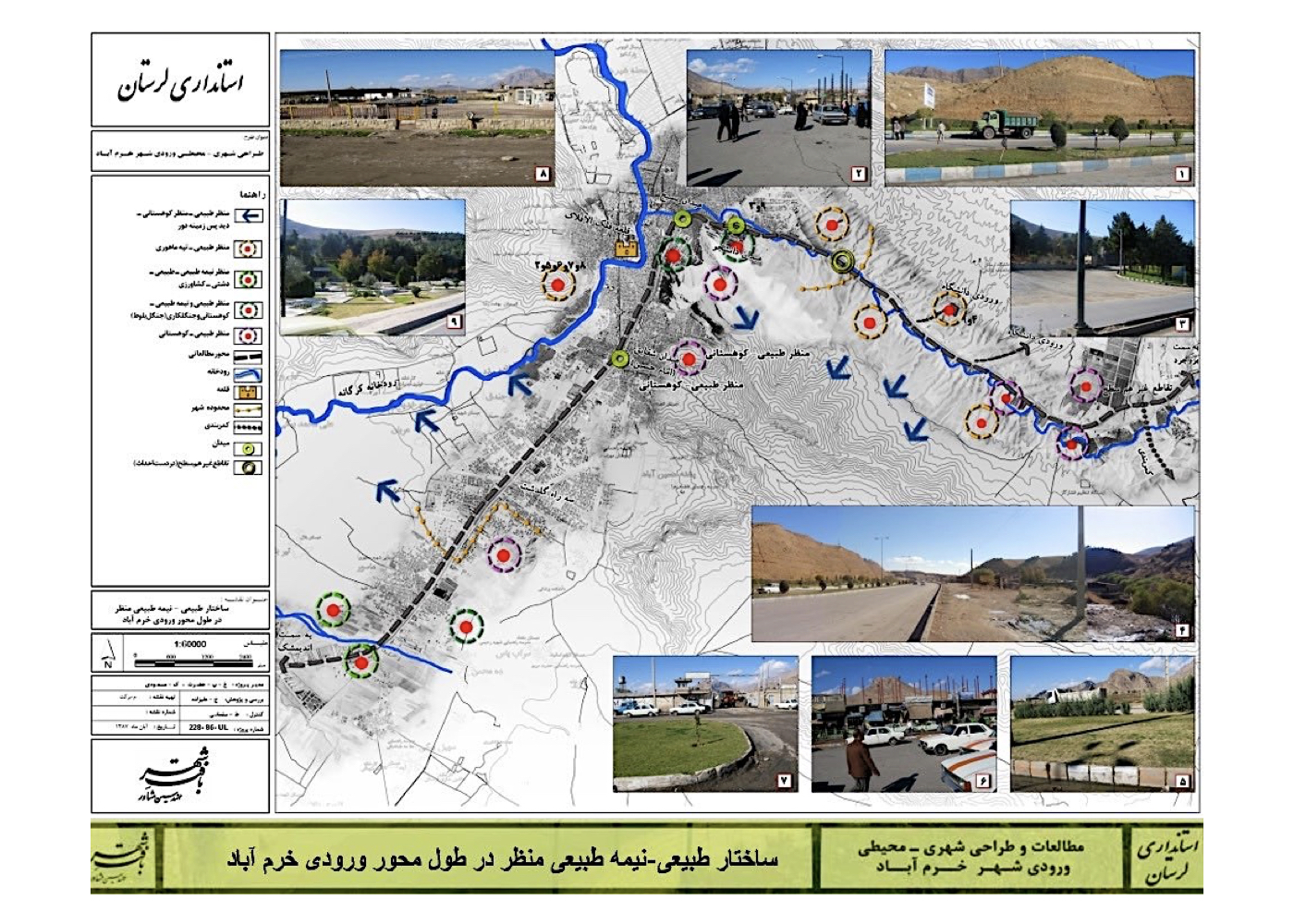

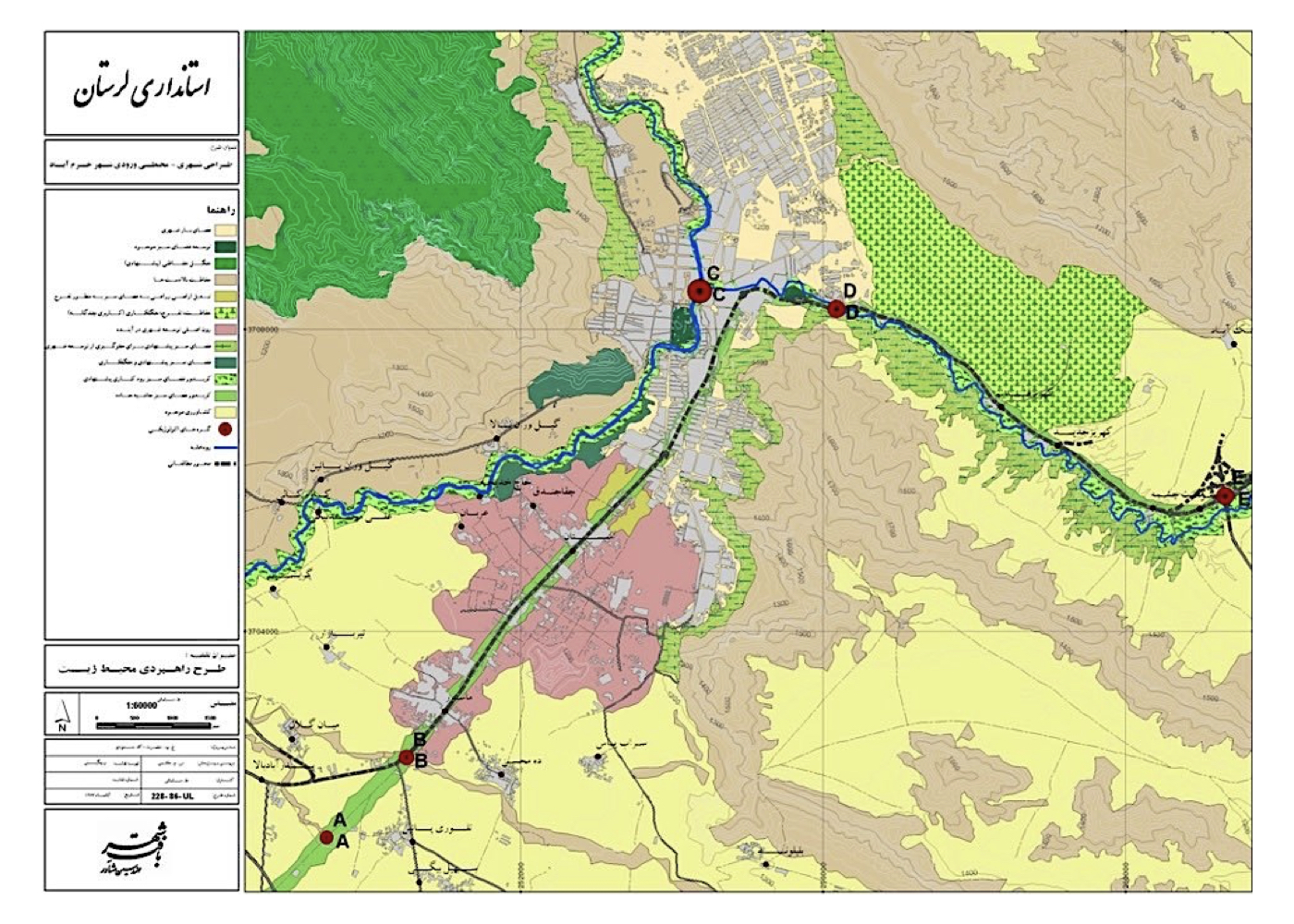

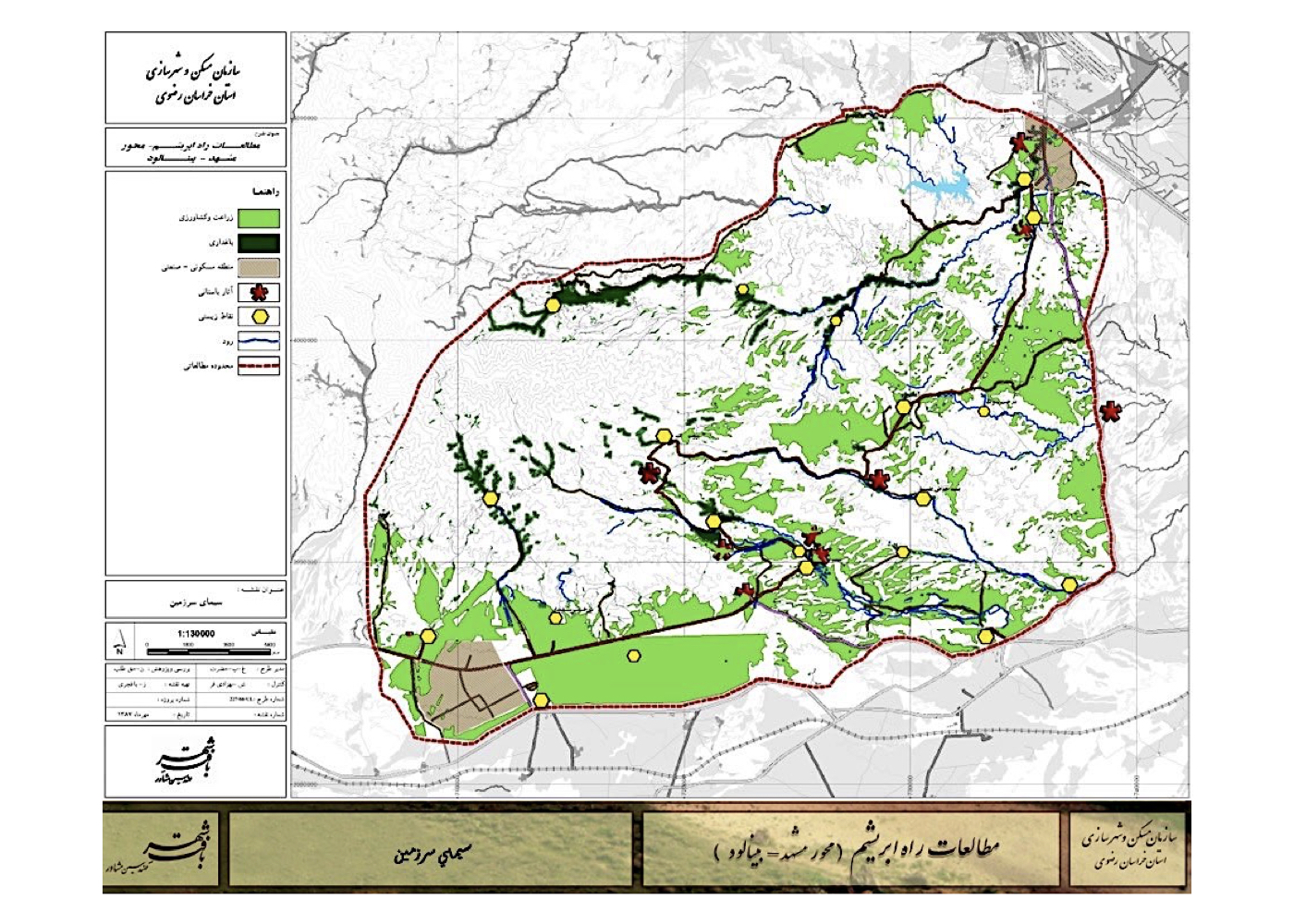

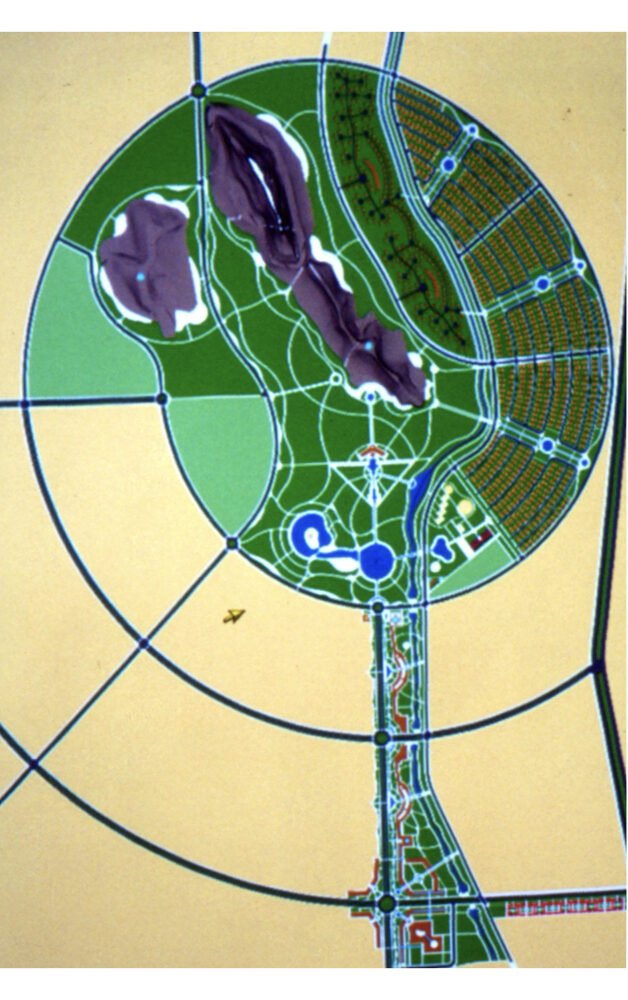

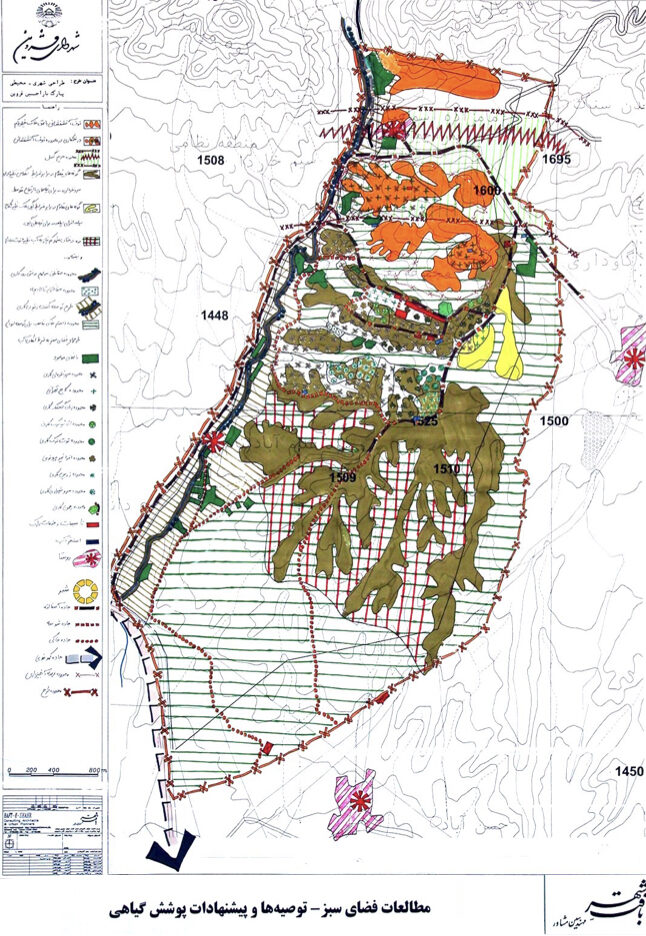

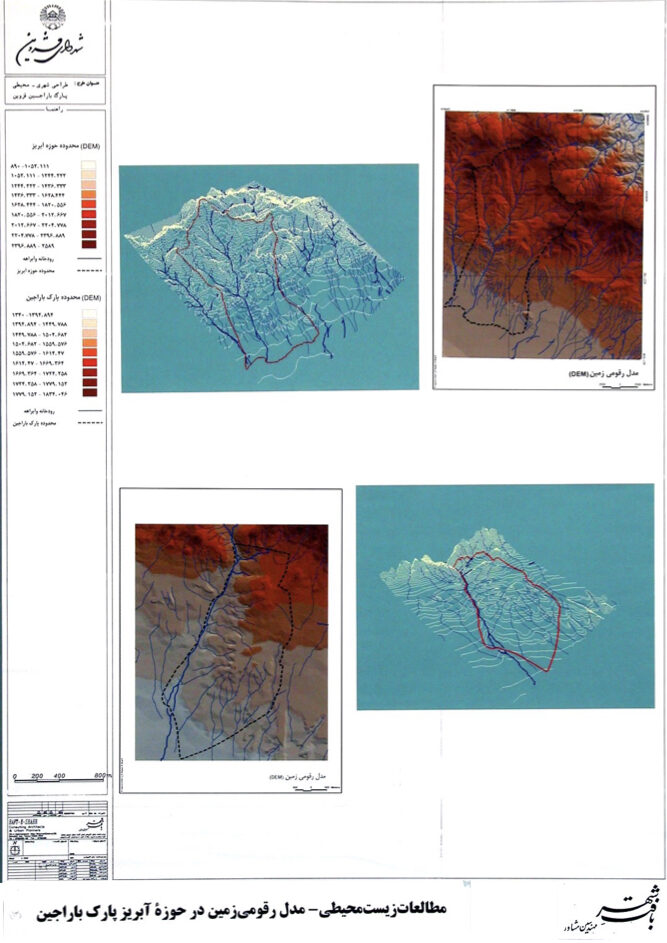

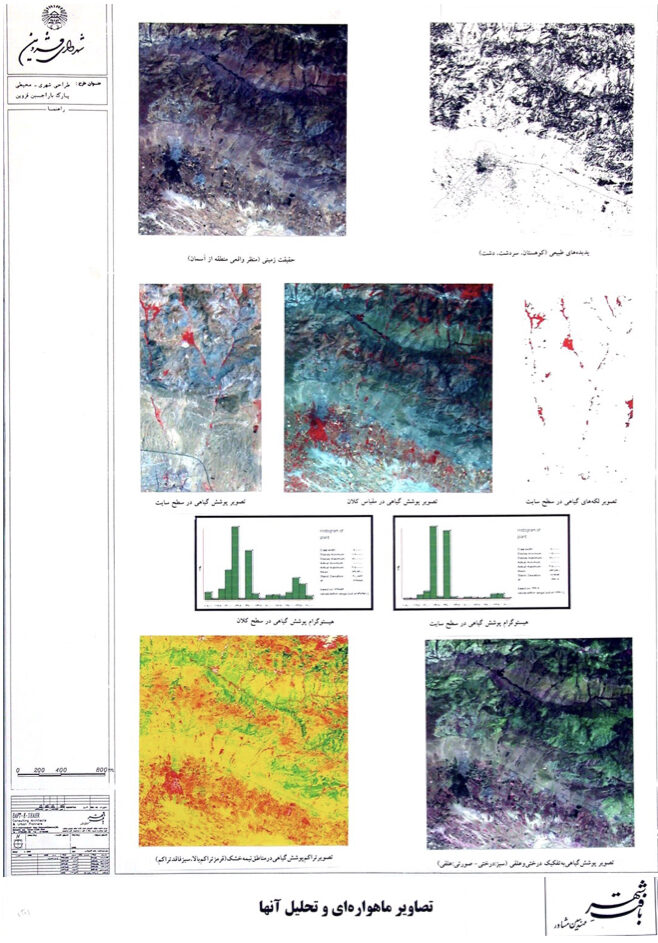

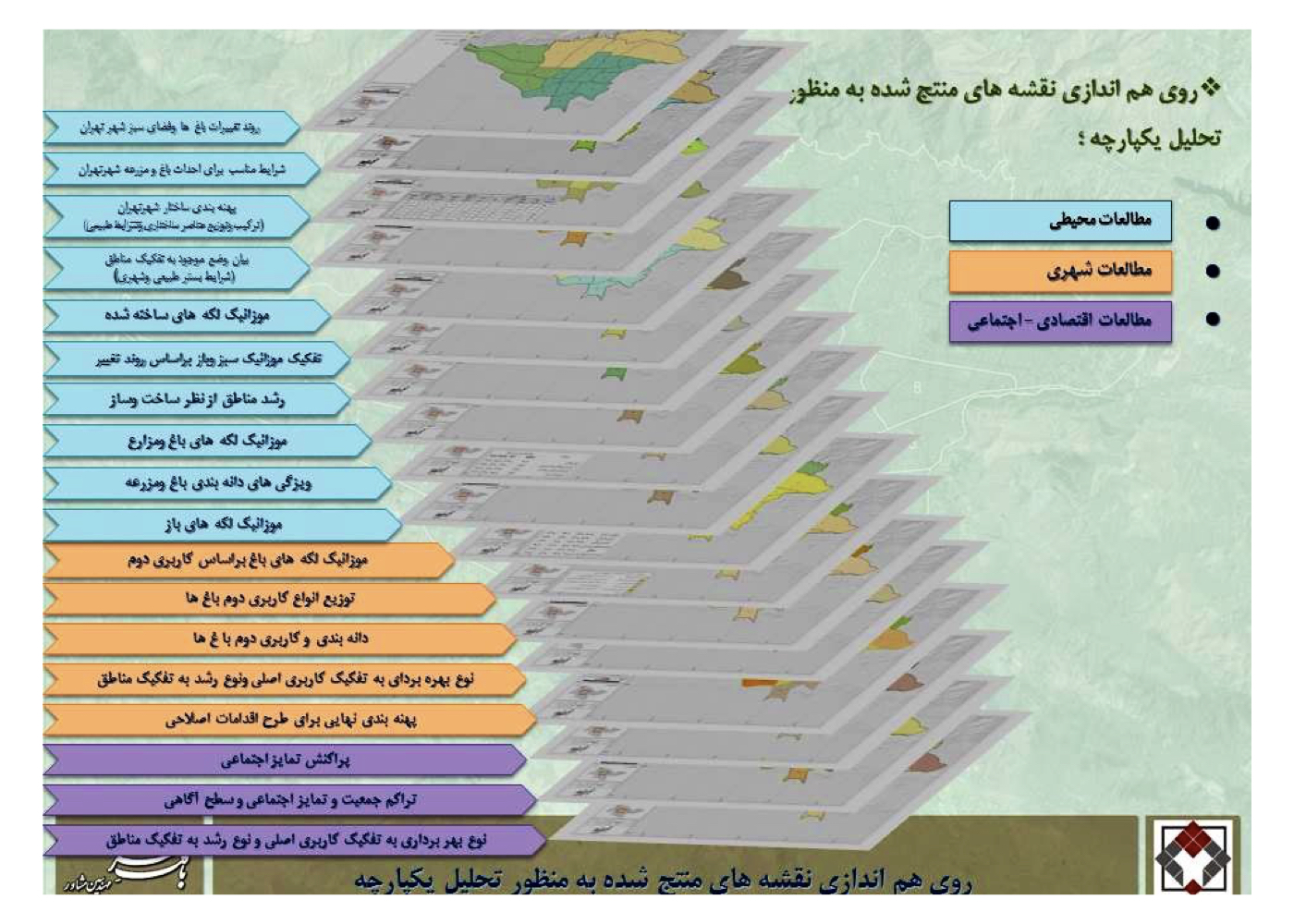

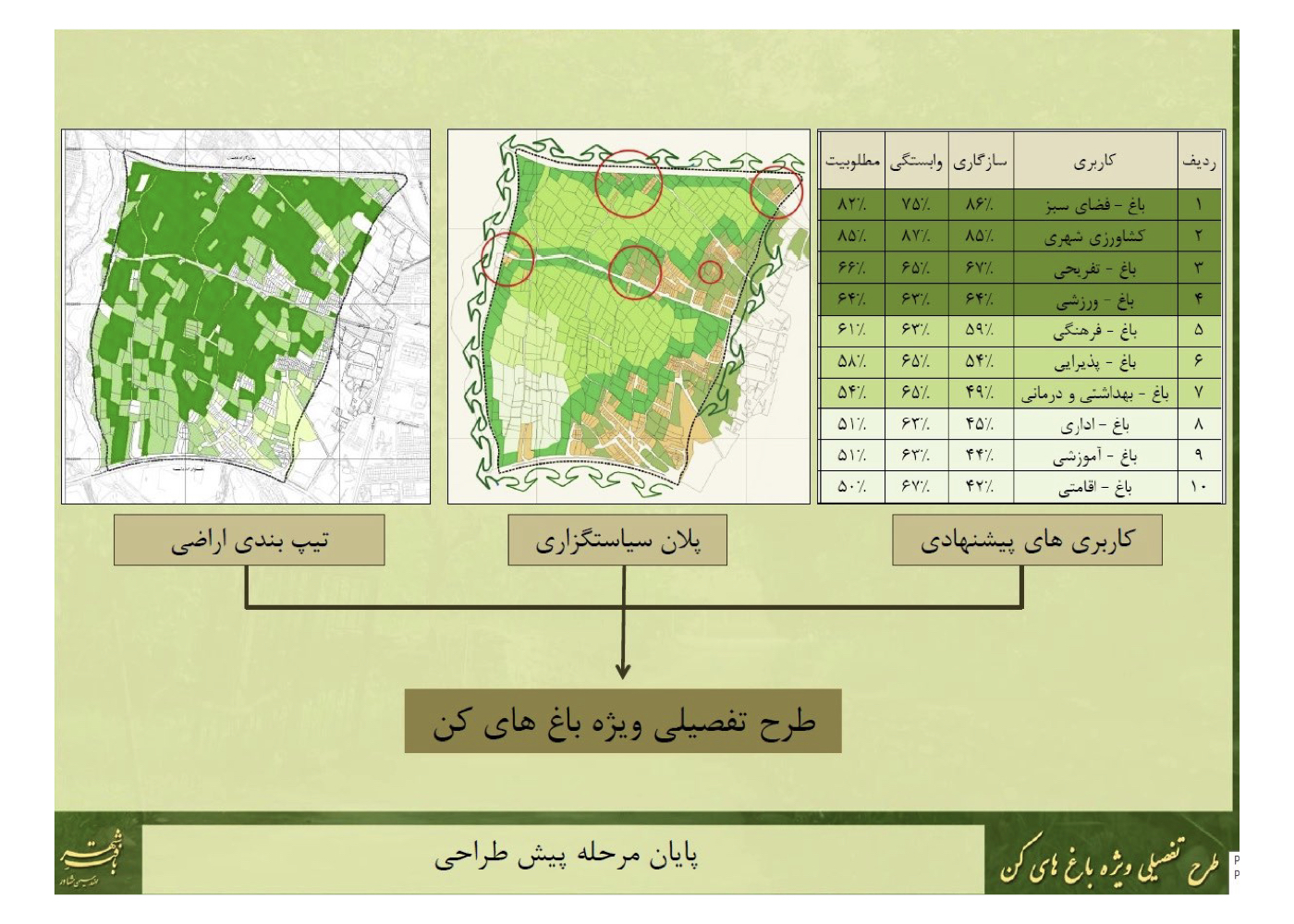

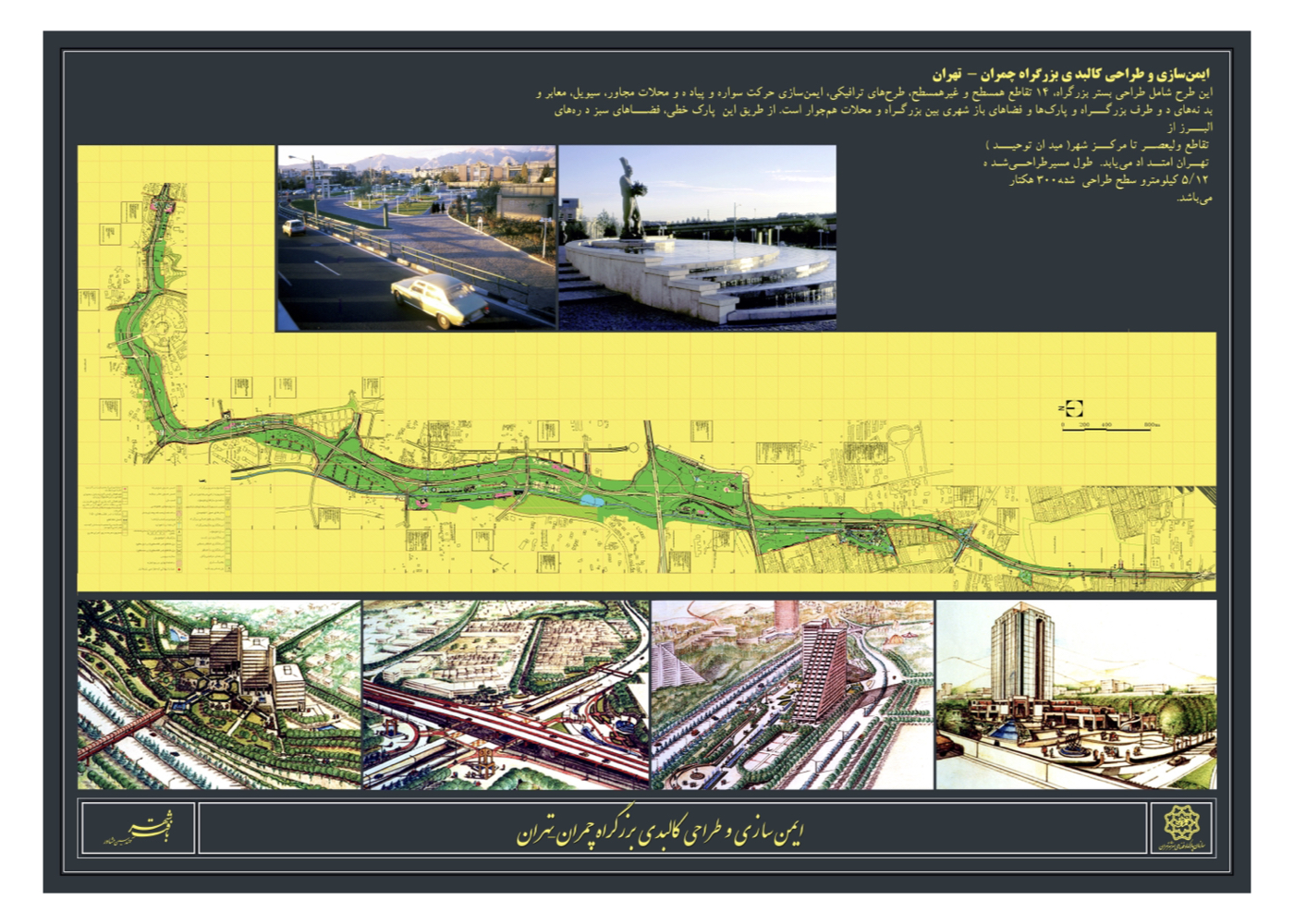

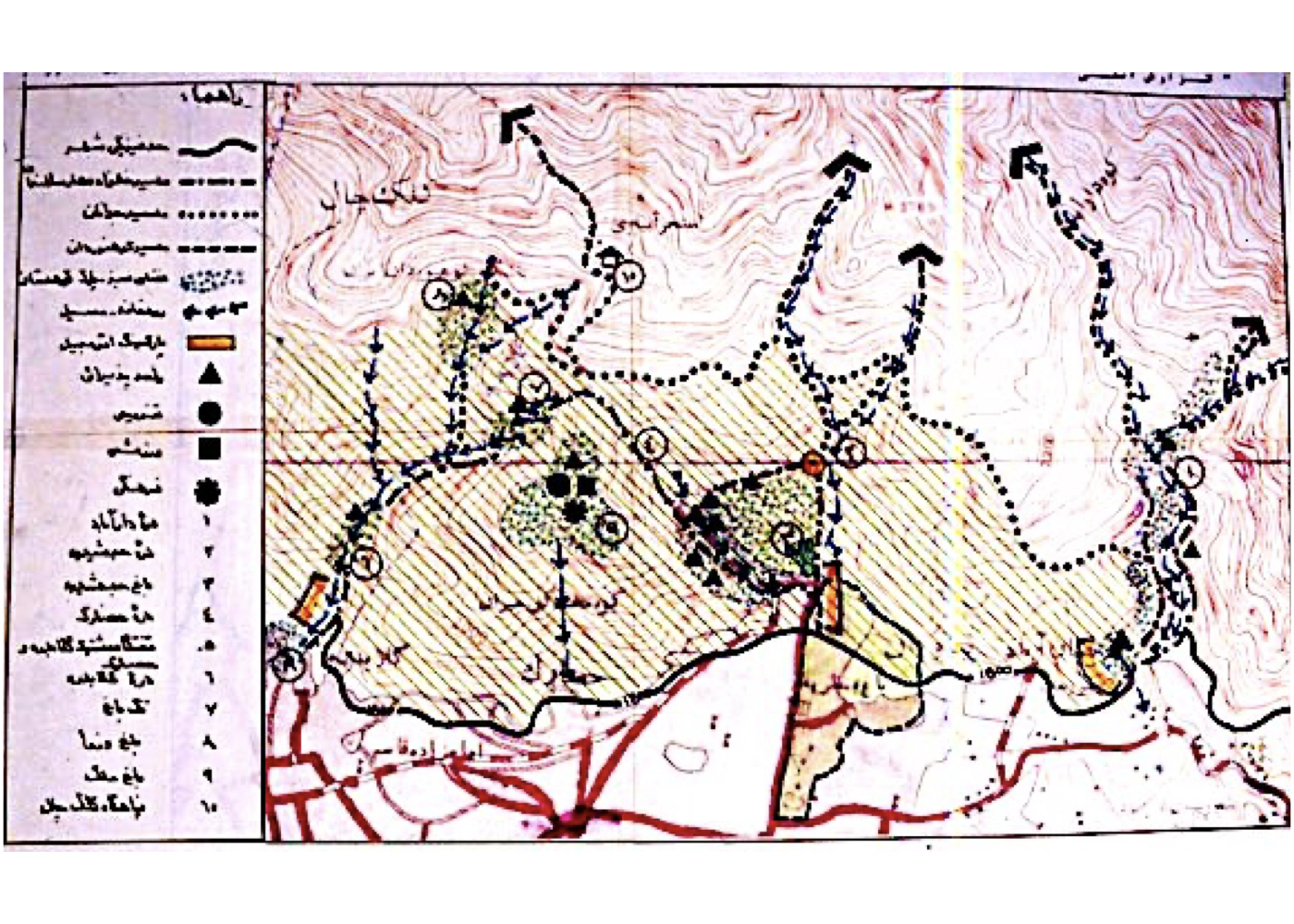

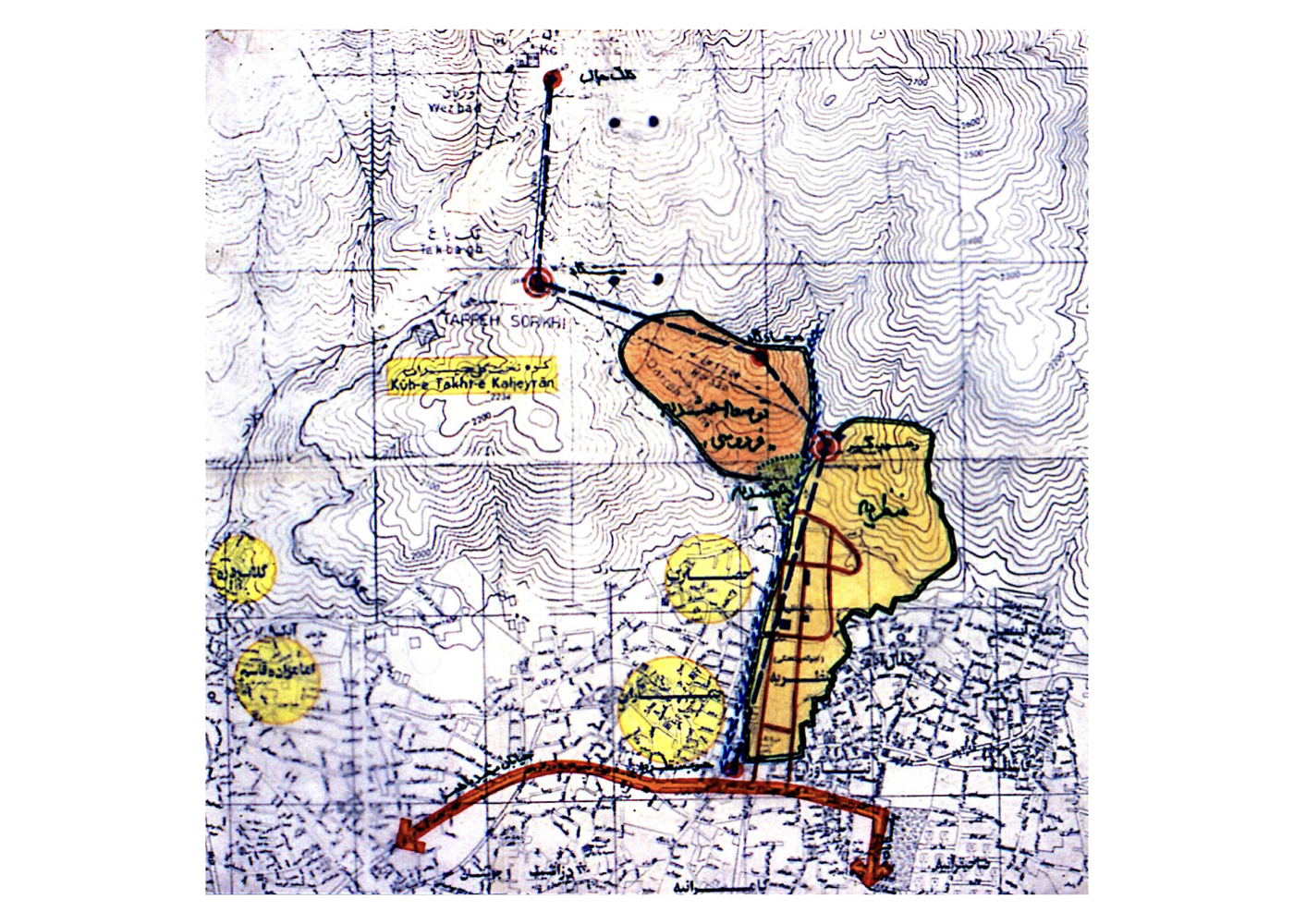

Over the past four decades, I have had the honor of directing the planning and design studies of several valuable natural assets in cities across the country. These projects were prepared and proposed based on the theory of “Urban–Environmental Design” and could have simultaneously protected and enhanced the environmental quality of these natural assets—resources that are the wealth, heritage, and foundation for continued healthy urban life—while enabling equitable, capacity-aligned, and sustainable use by citizens, improve people’s attitudes and relationships with nature, and contribute meaningfully to sustainable urban development.

However, fundamental changes to the plans, their incomplete implementation, or execution without the involvement of the original designers and under non-expert directives, often lead to deviation from the original vision, potentially causing harm, and distancing the project from its core objectives of natural resource protection and sustainable use.

The reports for these projects have been compiled over the years across various cities, amounting to several hundred volumes, and were developed through national funding and the dedicated efforts of experienced, committed professionals.

While it is not feasible to present all these reports here, summarizing the strategies, approaches, and recommendations of these projects for each city’s residents especially students and younger generations can raise awareness about the unique natural and historical values of our cities and nation, and foster their engagement in preserving these natural treasures and priceless generational heritage.

A Few Important Notes Regarding These Projects:

Some proposed strategies—such as enhancing human-nature-city interaction—are generalizable and applicable to similar urban contexts. In many of these cities, other relevant plans exist that are not covered here. Some plans were not executed—or only partially realized—due to funding gaps or changes in administration.

In Section 8 of this website, information is provided on Fourty urban–environmental design projects across 16 cities in Iran.